Montreal 1936: October's Child

The story of Patrick, Edna, and Jane

Patrick was working at a downtown restaurant when he caught sight of a waitress. She was pretty, of course, but it was more than that. She was the sort of girl who glowed. Patrick was awkward around girls. He didn’t know how to dance. He didn’t know how to talk to them. It was enough to watch her glide around the closely packed tables bagging tips with her bright smile.

Patrick’s parents, Jane and Tom, were Irish immigrants who had not married until they were both over forty. Patrick was a surprise, their one and only miracle, but they didn’t know what to do with a child. It was a lonely and joyless growing up. For Christmas he received unwrapped socks.

Patrick became the vessel for all of Jane’s unfulfilled ambitions, and it became his lifelong project to try to please her.

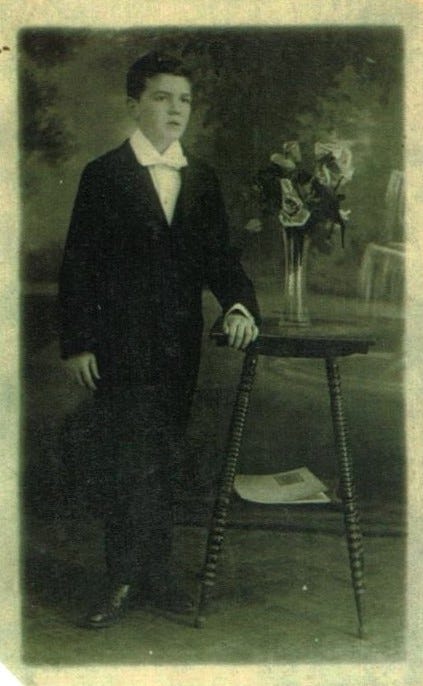

His uncle, the poet-priest D.A. Casey, wrote a poem entitled “October’s Child,” commemorating his birth, which occurred during the holy month of feasts of the Virgin Mary. His mother Jane was not saintly. Patrick became the vessel for all her unfulfilled ambitions and it became his lifelong project to try to please her. Jane gave him the middle name of Emmet, after Ireland’s Romantic hero, the patriot and orator Robert Emmet. She expected no less greatness from her son. She coaxed the bashful Patrick to sing in public. When a neighbor boasted her boy was sitting the exam for Catholic High, Jane decided Patrick would, too. Jane knew Patrick was brighter than any other boy and insisted that he skip a grade. Jane’s constant prodding, her stubborn insistence that he was special, made Patrick modest and shy.

Jane drank, which blunted some of her excessive attention to Patrick. When he grew older, he became her drinking buddy and her travelling companion. Patrick never drank too much. He was a quiet, cautious boy, always the one who kept his head and stayed alert.

Jane decided that her brilliant son must go to university. They knew no one who had gone beyond high school. For Jane, nothing less than McGill would do. Patrick took the streetcar to the corner of McTavish and Sherbrooke, and stood in line at the McGill admissions office with his report card. He was admitted at 15, and for decades after liked to say that he got his first pair of long trousers when he went to college.

McGill University in 1927 was a nonstop party. It was filled with Americans then, as now, most of them there to take advantage of legal drinking in Montreal. Pari mutuel wagering, outlawed in the US, was legal too. Young Patrick was good at adult games, anything that required numeracy and wiles. He wasn’t much for throwing a ball, but could calculate odds in his head. In college Patrick learned about all kinds of gambling: craps, poker, horse racing, but he loved hustling pool most of all. Jane had wanted her son to go to university but had no way to pay for it. McGill was $200 a semester then, and when tuition was due, Patrick would slip away to pool halls in the bas fonds of Montreal to play snooker. He’d be gone for days, returning with the tuition money in crumpled dollar bills.

One night at the card table, a rich American upperclassman ran up a $50 debt to him. The boy was much bigger and stronger than skinny 16-year-old Patrick, and he knew the boy would never pay him what he was owed. Patrick suggested that they keep playing, and for every game Patrick lost, he’d knock $2 off the debt, and for every game he won, the boy would give him $1 cash there and then. The boy agreed and Patrick set about throwing every other game. They played all night, and Patrick pocketed more than his father earned in a week.

He told his buddy that’s the girl I'm going to marry.

You’re nuts, said the friend. She’s engaged to someone else.

Patrick’s father did not lose his job after the stock market crash, but Patrick dropped out of school anyway. University seemed a pointless extravagance. He lived at home, unemployed, like most of his friends. He was twenty five when a friend found him the job at the restaurant, where he worked as the night cashier. He spotted a waitress coming in for the evening dinner service. He told his buddy that’s the girl I'm going to marry. You’re nuts, said the friend. She’s engaged to someone else.

The girl posed a challenge. This was a game he did not know how to play. He soon learned her name, Edna, and knew she worked the Sunday lunch shift. On Sunday mornings he got up early, and put on a suit and tie to stand at the corner of St. James and Peel to tip his hat to her as she flew by, holding onto her own hat, running from Mass, because she was late to work. How odd, she thought. Why is Mr. Casey always on the corner of St. James and Peel every Sunday morning?

After years of wandering looking for work, Edna’s family had settled east of the Main, in the Plateau, a poor French neighborhood of narrow streets lined with sagging triplexes. But Edna did not live there anymore. One night Edna had come home from a date and was saying good night to a boy on the front steps when her father flew out of the house drunk and yelling. He called her a slut and dragged her inside. Edna swore she would never live under his roof again. She didn’t need to. She was a good waitress and had been supporting herself and her younger brothers and sisters since she was fifteen.

She broke up with the boyfriend, whose name is lost. She never told anyone why they broke up but kept a portrait photograph of him dressed in his pilot’s uniform in her dresser drawer for years afterward.

She and Patrick started going together, but they had no money to marry. Edna suggested that Patrick go back to university. He only needed a few credits to graduate. He switched to a commerce degree because it was easier to finish while working. No one wanted to major in business back then. Business degrees were strictly for people with money to go to school who couldn’t read or write.

One day Patrick got the news that the RCA Victor plant in St. Henri was hiring. In those days, the word went out and people showed up at the factory and stood in line, hoping to be chosen. Patrick went to try his luck. When it was revealed that he was a college boy, he was told that he should apply at the office—there might be a job in accounting. Patrick did as he was told, and was asked if he knew how to use a comptrometer. He lied and said yes. He spent the next thirty years in the accounting department at RCA Victor and never saw a comptrometer.

Edna told Patrick she would marry him on the condition that he never gambled again. He played poker for matchsticks after that. Shortly before they married, they went on an overnight trip together. Patrick saucily suggested they share a room. Edna said no. It would have been embarrassing to be a pregnant bride, confirming what her father thought of her, but in truth she was worried it was a test, that he wanted to check that she was a good girl. It would never have occurred to Patrick to test her in this way, but she couldn’t know that. Such was the world of men and women then.

Patrick and Edna married in 1937. Edna’s father never used Patrick’s name and only referred to him as l’Anglais.

Some years before, Patrick’s father had bought a two-family house in Notre Dame de Grâce, an Irish neighborhood that had sprung up past the end of the streetcar line. Edna and Patrick moved into the flat downstairs. Upstairs, Jane would drink and issue directives. Edna loved her father-in-law, the gentle Tom, and called him Dad. She did not like Jane, especially when she drank. She’d had her fill of living with a drinker. Each morning Patrick went to work leaving a house with two volatile women in it, never sure what he would come home to.

Patrick never achieved more than temporary cease fires between them. Edna admired Jane’s long russet hair, glossy and thick. Edna did not like her own hair, which was thin and fine. In peace times she loved to wash and brush Jane’s hair for her. After Jane was gone, whenever hunting for something kind to say, Edna remembered her beautiful hair. She had red hair until the day she died.

Money was tight when they were first married, but Edna grew up poor and knew how to stretch a dollar. She could fix anything. All the French tradesmen and storekeepers in the neighborhood knew the charming young mother who could press them for better prices in their own language, cut with the accent of their own people. One Christmas when they were first married, Patrick came home with an exquisitely wrapped box from Holt Renfrew. It was a beaded evening bag. Edna looked around at the drying diapers hanging in the kitchen and wondered when she would ever need such a thing. She thanked Patrick, then wrapped it up and quietly took it back to the store, exchanging it for cash, which she used to buy groceries. Patrick never knew what became of the bag. He never asked.

Edna and Patrick had four children: Patsy, Joan, Tom, and Maureen. Jane had no use for small children. Get away little boy she would say to baby Tom. Patsy, the eldest, named after her father, was however Jane’s darling. Patsy’s sister Joan was born the following year. Thereafter, Jane referred to them as “Patsy and the other one.” Jane rigged up a basket of candy on a hook and a string, and lowered it downstairs to Patsy. Jane leaned out the upstairs window with a showy stage gesture of finger on lips. Just for you Patsy! But Edna had grown up with eight younger siblings and had eyes in the back of her head. She intercepted the candy as it lowered on its hook. “All the children will share this later. And my other daughter has a name. Her name is Joan.”

Patsy would go upstairs to visit Jane and be lectured on the manifold wrongs done to Ireland. Jane would give Patsy hard caramels and terrorize her with tales of the Black and Tans. The Black and Tans burned the houses of little Irish children. They shot Catholic people in the street. The Black and Tans became bogeymen haunting Patsy’s dreams.

Jane died in 1946. Patrick’s father Tom moved in with Patrick’s family. Edna cared for him until his dementia became too advanced for him to remain at home. The children grew up.

Edna was playing with her grandson when she felt the lump. Patrick took early retirement from RCA, at the age of 55, to be with her. One day not long before she died, she told Patsy that she should have kept the evening bag. It was 1972, and she was 59.

When they still lived together, when his children were still little, Jane and Patrick would go out once a week, just the two of them. Each spring, for thirteen weeks, they would go to St. Ann’s, the old parish church in Griffintown, to “make the Tuesdays” an evening devotion to Saint Anthony, the patron saint of childless couples and lost things. After Jane was gone, Patrick went alone.