In the winter of 1688 my Morin ancestors were expelled from their village of Beaubassin, Nova Scotia. They walked into the wilderness taking only what they could carry.

The exile of the Morins is an Acadian legend. But to understand why they were banished requires learning the story of Beaubassin—a tale of a great marsh, an interloping seigneur, a sex pest, a village rebellion, a witch trial, and a forbidden love.

The first installment may be found here:

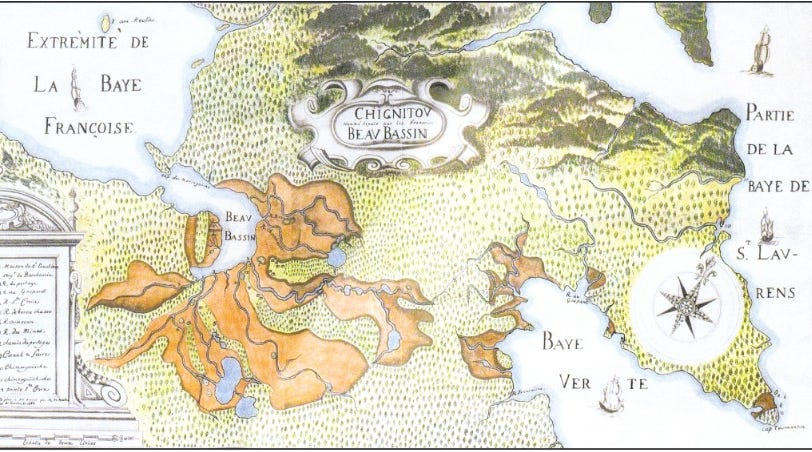

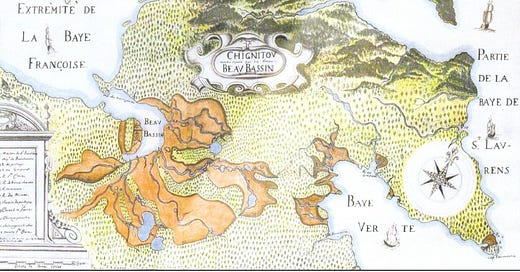

The story so far: In 1671 Jacques Bourgeois and his family establish a new settlement at Beaubassin, in the marshlands where Nova Scotia meets New Brunswick. They are joined by others seeking independence, including Pierre and Marie Morin. Everyone at Beaubassin is engaged in back breaking work of draining the marshes for farmland. Then, in 1676, the rulers of New France grant Beaubassin to Michel Le Neuf as his noble fiefdom.

In this second installment we meet the new master of Beaubassin, Michel Le Neuf and he meets his villagers.

Michel Le Neuf was the third son of Jacques Le Neuf de La Poterie, a slippery bootlegger and fur trader who became Governor of Trois-Rivières.1 Michel Le Neuf was not Acadian but he was born in New France. Genealogical research suggests that the Le Neufs were not noble but social climbing Huguenots who concealed their Protestant origins.2 Protestants were banned from New France, and at least one was executed in Quebec for heresy.3

The French new world was afflicted with the legal order of the old. The seigneur had rights and privileges in his fiefdom, or seigneurie. He received rent, in cash or kind, and controlled wood-cutting, hunting, and fishing on his land. The seigneur also served as the court of law, meting out justice for low-level misdeeds and settling disputes. Tenants had to grind their grain at the seigneur's mill. The seigneur could also require work on his behalf. This unpaid labor was known as the corvée.

Enforcing seigneurial rights in the new world was a challenge. The vast wilderness gave habitants a choice of where they wanted to settle. A seigneur who pushed his settlers too far could not keep them on his land.

Michel Le Neuf was pushy with a short fuse. He was however well liked by Frontenac, Governor General of New France, who said Le Neuf could one day be Governor of Acadia, as he had “all the qualities of mind and heart necessary to acquit himself well in such a post.” 4

Le Neuf had never lived in Acadia and did not lay eyes on his seigneurie before it was granted.

He was given sole hunting and fishing rights on his domain, without mention of any other seigneurial privileges.5 And he was instructed not to meddle with settlers who had been there first.

Beaubassin’s new master finally appeared in Beaubassin in 1678. Wary villagers watched Le Neuf’s imperial entry on his own sailing vessel, the Saint Antoine, and studied him as he disembarked with Madame Le Neuf, their seven children, and servants. These Acadians had not met many men from New France. All they knew was that before they had been free to hunt and fish, and cut down any tree they wished. Now this interloper was claiming everything as his.

The new seigneur established himself in feudal style on a hilltop at Île de La Vallière6 perched above his swampy domain. He took stock of his villagers. They were a tight knit group. The founders had adult children and this second generation had intermarried, creating a dense web of family ties. By this time, the settlement numbered about a hundred people, not including the Mi’kmaq.

Le Neuf noted what visitors to Beaubassin had told him— there still wasn’t much wheat being grown. Houses rose out of the marsh on tiny islands of dry ground. The villagers used the available hillsides to feed their beasts. A lot of the community’s goods, even food, was being purchased from the English, to whom they had racked up debt.

He needed to step up work on draining the marsh. And if settlers were buying from the English, Le Neuf also wanted to start his own trading business. Le Neuf also wanted a new mill to replace the ramshackle one that the Bourgeois family had built. This one would be his, and the villagers would pay him to use it, as was his right.

And there would be still more to do. Grandiose talk in New France of building a canal through his domain connecting the Gulf of Saint Lawrence to Fundy fired his imagination.7 Le Neuf threw himself into all projects at once.

When approached about building the mill, Cormier, the carpenter, had no time for extra work. Then Le Neuf, to his annoyance, spotted Cormier strolling on the ridge with his cows on sunny days. Le Neuf’s man, Haché even saw Cormier heading home with his gun and a pair of rabbits slung over his shoulder —rabbits belonging to Le Neuf. And Cormier wasn’t the only one flouting the rules. In the end, the seigneur sent for a carpenter, Pierre Godin, from Port-Royal.

The seigneur issued proclamations from Ile de la Vallière. The Missiguash River, a wide shallow channel that wended its way through the marsh and served as Beaubassin’s main street, would henceforth be known as the Marguerite River.8

Missiguash was the Mi’kmaw name for an animal hunted for its dense, waterproof fur. The local people revered this animal. They said it had dived to the bottom of the primordial sea to bring up mud creating the Earth when all other animals had failed in the task. The villagers agreed that changing the name of their river was a bad idea and, given the swamp clearance they were doing, possibly a bad omen.

The problem of draining that fuggy swamp consumed Le Neuf. There must be a way to get work out of these men. A few were less aloof—Morin and Kessy. They had only been in Beaubassin for a few years and their families were not part of the sailor’s knot of villagers who all seem to be each other’s in-laws. But when Le Neuf asked them for some spade work, Morin and Kessy always had some other task at hand.

Le Neuf wrote to New France to get more ploughmen. But it would be easily a year before anyone would be working in Beaubassin, and the imported manpower was not enough. The work crew was right under his nose, but tantalizingly off limits: the men of Beaubassin.

The solution was simple— he would disregard his instructions and impose the corvée.

The seigneur told the villagers that anyone on his domain would need new contracts. These new contracts entitled him to the corvée. The men of Beaubassin refused to sign.

At first, Le Neuf tried to persuade them, describing the rich pastures they would all enjoy if only they worked together on his designs. He personally called on each one of these penibles, rowing through the marsh, walking through the muck, his tall boots sucking into the mud, to come to their houses. But no man was ever home. The wife, her face a polite mask, claimed not to know where her husband was, and had no idea when he was coming back.

Le Neuf knew their men were out in the marshes, hiding in the tall reeds. He was sure they were sometimes mere yards away. But to have Haché pursue them was a mistake. They knew the marshes, the winding water channels, the mud tunnels. He and Haché had already seen how a man could vanish into the mist.9

Smooth talk did not work. Le Neuf knew he could not use brute force, either. He and Haché and his other men were outnumbered by the villagers, who each owned a gun.

If Le Neuf arrived thinking he was going to lord it over the people of Beaubassin, he now knew he was mistaken. From Quebec to the Court of Versailles, Acadians had already made it known they were a different breed. In a letter to the King of France, Le Neuf’s mentor Frontenac admitted that the people of Beaubassin weren’t good at taking orders.10

Next: Disaster befalls the village, and Le Neuf gets help from a stranger.

Many thanks to Gary Tucker for his sublime photographs of the landscape surrounding the historic site of Beaubassin. If you wish to see more of his extraordinary work, or order a print, his website may be found here: https://garytuckerphoto.com/

Lamontagne, Léopold, LENEUF DE LA POTERIE, JACQUES, Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1 University of Toronto/Université Laval, 1966. https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/leneuf_de_la_poterie_jacques_1E.html accessed April 23, 2025

“Le Neuf Family Research” https://habitant.org/leneuf/ accessed April 3 2025.

Vachon, André, “VUIL, DANIEL” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 1979. https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio.php?id_nbr=580 accessed April 8, 2025.

Comeau, J.-Roger, “LENEUF DE LA VALLIÈRE DE BEAUBASSIN, MICHEL (d. 1705),” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 2, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/leneuf_de_la_valliere_de_beaubassin_michel_1705_2E.html accessed April 10, 2025.

Acte de concession de Sa Majesté à Michel Leneuf de la Vallière du lieu nommé Chignectou par les Sauvages et en français Beaubassin, situé au fond de la baie Française, 24 octobre 1676. Bibiliothèque et archives de Québec (BANQ) Collection Seigneuries CN - 03Q, P240,D5,P1 https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/4754653 accessed 6 April 2025.

Now Tonge’s Island

It should be noted that Le Neuf’s concession was conditional on developing the land and he knew it could be taken from him if he did not.

It’s not clear when Le Neuf changed the name of the river. It may have been changed after the birth of his daughter Marguerite in 1780, but Madame Le Neuf had given birth to a daughter named Marguerite in Trois- Rivières some ten years before who had died as a baby.

The villagers of Beaubassin here demonstrate a perfect example of “weapons of the weak.” James C. Scott's Weapons of the Weak: Everyday Forms of Peasant Resistance (1985) is a seminal work in the field of political anthropology that focuses on the "everyday forms of resistance" employed by rural poor against their oppressors. "Weapons of the weak” are not dramatic acts of rebellion but rather "foot dragging, evasion, false compliance, pilfering, feigned ignorance, slander, arson, sabotage, and so forth." Minor, even petty, acts by small groups are forms of passive resistance that can effectively undermine the power of landlords and elites. Scott argues that these subtle forms of resistance are often more rational and effective for peasants than open rebellion.

Daigle, Jean. “Michel Le Neuf de La Vallière seigneur de Beaubassin et gouverneur d’Acadie, 1678-1684.” Thèse de maîtrise, l’Université de Montréal, 1970, p. 86, quoted in Carol A. Blasi, "Land Tenure in Acadian Agricultural Settlements, 1604-1755: Cultural Retention and the Emergence of Custom (2019). Electronic Theses and Dissertations 3053. accessed April 9, 2025. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd/3053

Lessons in resistance!

"weapons of the weak" -- 😊