Griffintown 1861: Molten Metal

A life retold from a single sentence

A family begins with a story. As it gets handed down through the generations the story gets sparser. Entire lives become distilled to one sentence. Just as sugar becomes cane syrup becomes molasses becomes treacle, it burns away until only the sulphurous black caramel remains: a feud, a crime, a journey, an act of bravery, or an impossible love.

My Maguire family story begins with one sentence: A Scottish Presbyterian girl was disowned for marrying an Irish Catholic. In the telling, there was sometimes a second sentence: The girl chose the Irishman over the family fortune. I heard this story growing up. Who was the girl? What was the fortune?

I can tell another one-sentence story: In Montreal, in the winter of 1861, nineteen-year-old Marion Gordon was unmarried and pregnant. But this tale starts with her father, John Gordon. A man who could bend iron.

John Gordon was born in 1803, in South Leith, Scotland, the son of a carpenter. John apprenticed as blacksmith. In 1828, he married Mary Milligan from North Leith. Mary was already pregnant at the time of their marriage. She and John would go on to have eleven living children.

In 1831, John and Mary, with their children Elizabeth, Mary, and Alexander, moved to Glasgow to seek their fortune. Glasgow had grown up overnight. Textile factories, glassworks, and shipbuilding brought Irish immigrants and desperate Scots displaced by the Highland Clearances. The Gordons settled in the industrial suburb of Finnieston. Most of the Gordons’ neighbors were Irish migrants employed by the Verreville Glass and Pottery Company. Finnieston’s skyline was dominated by the company’s multi-storey brick cone. It looked like the nest of a stinging insect and filled the sky with smoke from its many furnaces. Finnieston’s cotton spinning mill worked children as young as thirteen in twelve hour overnight shifts. As more migrants poured into Glasgow, the cheaper labor cut wages, causing riots. Cholera ripped through the overcrowded streets, killing entire families.

Glasgow newspapers were filled with advertisements seeking skilled tradesmen in America and all over the British Empire. In this hard luck place, John somehow got his hands on enough money for the fare to Canada, as well as some start up capital. In 1843, the Gordons sailed for Montreal, where John started his own forge. He never worked for another man again.

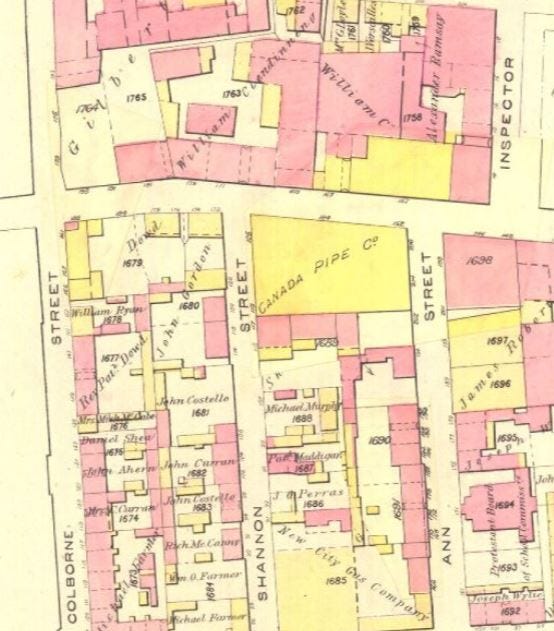

The Gordons were starting over in a place not all that different from Glasgow. Montreal was crowded, dirty, and filled with poor Irish and Scottish migrants. John set up his smithy in the Brickyards neighborhood of Montreal’s Griffintown. He could not have picked a worse time to arrive. The city was in the middle of an economic depression that saw businesses failing every day. Prices for land and buildings in Montreal were as high as in European cities—out of reach for ordinary working people. But John had enough money to buy his own home, and he knew right away that the easiest and surest money was in real estate.

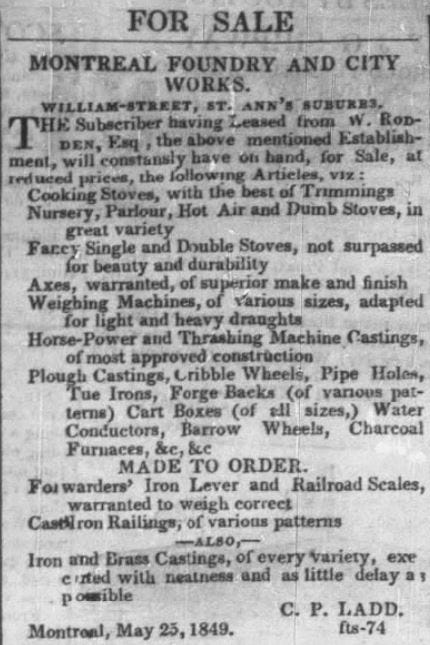

John’s forge was soon dwarfed by the factory-like foundries growing up around him. Eagle Foundry, on King Street, built industrial machinery, boilers, engines, and presses. Clendinnings, first known as the Montreal Foundry and City Works, across the street from John’s shop, employed a hundred men at its height and manufactured every kind of metal good: tools, bedframes, stoves, iron railings, as well as castings, machinery, railway ties and boilers.

John’s shop made small items, such as stamps and tools. John and his grown sons spent their days sweating in leather aprons, working in one small, dark room: small to concentrate the fire’s heat, and dark to make it easier to see the glow of the metal. John’s young daughters would not have been allowed inside. The forge was cramped and filled with hot, sharp things. Next to the forge was a yard for scrap and fuel, and that yard would have been filled with men.

The blacksmith shop was a gathering place. In the winter, its fire drew passersby to warm up for a few minutes, or to stay longer if they lived without adequate heat. Through the long, bitter Canadian winters, the raggedy men of Griffintown passed the day hanging around Gordon’s forge. Unlike the big foundries, John’s yard was a good place to kill time and hear gossip, news, and prices. Since it was his workplace, John did not spare time for idle chatter, but he no doubt heard things. He learned when a vacant lot was going up for sale. Who had got turned out of their flat and what the rent of the vacant space would now fetch. Who had gone bust and was now selling tools and horses for cheap.

Most blacksmiths had a sideline as money lenders. John earned additional income by sharing his home with tenants. Given the high cost of housing, space was at a premium, so Griffintown flats were divided and subdivided, with people passing through another family’s flat to reach the back stairs and the privy, and tenants leasing to subtenants the use of kitchens and yards, even doorways and stairs. With rent and other income, John started amassing enough cash to buy more property.

In 1852, a fire swept through Griffintown, burning down all of Shannon Street. The fire smoldered for days, with hapless residents picking through the ruins for their belongings and being gouged by carters to haul away the remains. John bought some of the now vacant lots, just steps from his home on William Street. On one of the lots he built a new house for himself, and a new forge. Next to them he constructed two storey brick tenements that held eight more flats. He did not sell his family’s old home on William Street but instead rented out more flats.

By this time the family also included Peter, Ann, William, and Isabella, all born in Glasgow. Marion, also born in Glasgow, was just a toddler when the family travelled across the Atlantic. Two more girls, Jessie and Jane, were born soon after the family arrived in Montreal. Their mother Mary had only a few short years to enjoy her fine new home on Shannon Street, an eight room townhouse that must have sat grandly on a block filling up with brick commercial buildings and tenements. Mary died in 1855, after taking the gamble to start over twice in her married life, and after twenty years of nonstop child bearing.

John was going up in the world. With the advent of horsedrawn trams, landlords and business owners were moving to better neighbourhoods, but John chose to stay in grubby Griffintown. It was near his workplace and rental properties, so he could monitor his investments closely. The neighborhood remained crowded, dirty, and chaotic. Griffintown had no source of drinking water, but there was a bar for every 150 people. The papers regularly reported drunken fights, crime, strikes, sectarian mobs, and shivarees. The low-lying streets flooded every spring when the St. Lawrence overflowed its banks, forcing its residents to flee to cleaner, drier places. These floods created a veritable mad tea party of real estate, with people moving in and out of different flats and storefronts each year. Cholera, typhus, smallpox, and other infectious diseases followed the dirty water. Three of the Gordon children, Mary, William, and Isabella, vanished from the record after the family arrived in Montreal.

Growing up in the streets of Griffintown, Marion and her siblings saw Irishmen drinking, fighting, and loitering in front of their father’s shop, forever warming their hands at his fire. The Irish population exploded in Gordons’ first years in Montreal. In 1847, Gordons witnessed the arrival of seventy thousand sick and starving people, more than the population of the city itself, and watched helplessly as thousands of them died that summer in the fever sheds of Peel Basin, just a few minutes’ walk from their home.

Many Irishmen in Griffintown were iron workers, employed by the big foundries, the Grand Trunk works, or the factories along the Lachine canal. Two of John’s tenants were immigrant ironmen: a fettler named Patrick Glavin and his adopted son, an iron moulder named Michael Maloney. In Griffintown, Protestants generally rented only to other Protestants. John Gordon did not care to follow convention and took the risk on Irish Catholics, including Glavin and his family.

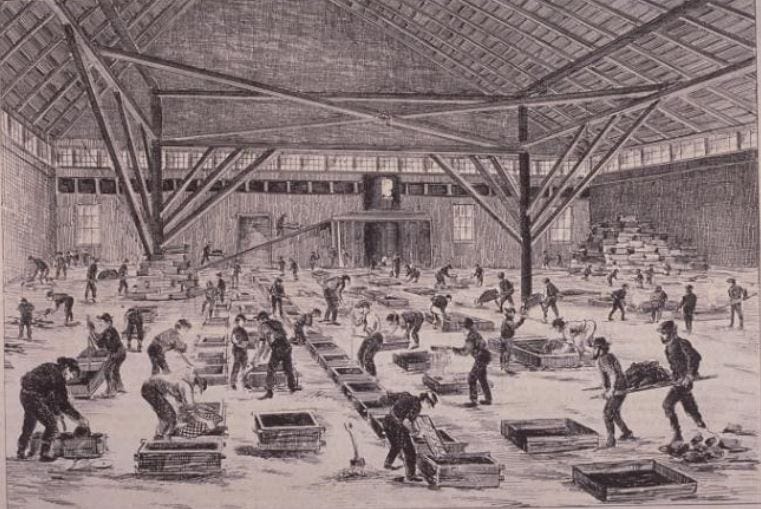

While a blacksmith worked by heating and softening metal to shape it with hand tools, foundries made cast iron objects molded from liquid metal. Michael, as a moulder, was the most skilled man in the shop after a multi-year apprenticeship that began at 13 or 14. Moulders also needed great physical strength, so Michael was a strapping young man.

The moulder's work day began by installing frames for casts. Sand was mixed with coal dust and clay, then placed in the frames. Pressing a mold into the sandy mixture created the imprint in which the molten metal would take its shape. The moulder spent much of the day making casts, then, in the late afternoon came the final step. Liquid iron, melted to white heat, had to be transported at a dead run, from the furnace to the mold. This step was carried out by the moulder alone. As a younger teenager, Michael would have been a moulder’s assistant, carrying sand, shoveling sand, or stoking the furnace. Other workers carried out additional tasks. As a fettler, Patrick Glavin filed down seams or imperfections from the metal casting. But the moulder stood at the apex of foundry work.

Meanwhile, adolescent Marion was out in the Griffintown streets unsupervised and unprotected. Her mother had died. Her older brothers were busy working with her father. Her only surviving elder sister Ann had left home to marry another blacksmith, an Irish Protestant named Henry Roxborough. In the new year of 1861, Marion Gordon found herself pregnant.

Marion and Michael could have met a number of ways. Michael worked in the neighborhood, perhaps at Clendennings across the street. He may have whiled away free time by the fire with the other men at John’s forge. He may have delivered the rent to John on behalf of the Glavins.

On January 16th, 1861, Marion and Michael Maloney married at the Erskine Presbyterian church. Her father did not attend. Instead, her sister Ann signed as witness. Nineteen year old Michael had no family as witnesses. The Glavins likely did not want to go inside a Protestant church, so Michael’s witness was Laurence Costello, a fellow moulder from the neighborhood who was Catholic but not afraid of Presbyterians.

This ceremony was the last one for Marion in her family’s church. Their daughter Mary, born that June, was baptized Catholic, and Marion became a parishioner at Griffintown’s new Irish Catholic church, St. Ann’s. At first, Marion and Michael lived on their own on nearby Ottawa Street. In the first year of their marriage, Marion’s younger sister Jessie died at the age of nineteen. Michael and Marion soon after moved into one of her father’s rental flats next door to his forge.

If this was a rapprochement between John Gordon and his prodigal daughter in wake of Jessie’s death, it was either short-lived or insincere. Tragedy struck at Christmas 1865. Michael was dead at the age of 24. Marion immediately moved out of the flat on Shannon Street to a rear tenement a long walk from Griffintown. A “rear tenement” was a wooden plank cabin in the rear yard behind a tenement, next to the main building’s outhouse.

The move to this shabby address could only mean one thing: without a breadwinner Marion could no longer afford the home she shared with Michael, and her father would not allow her to stay there rent free.

Marion and her daughter lived in that rear yard for five years. Marion must have survived as other widows did, by taking in piece work or cooking hot lunches. City enumerators frequently forgot people who lived in rear tenements, but when Marion did appear in Lovell’s directory she was “Mary Maloney.” Scottish Presbyterian Marion Gordon was gone, reborn and renamed Mary.

Michael Maloney’s family eventually rescued Marion and little Mary from their squalid lodgings. In 1871, Marion returned to Griffintown to live with Michael’s adoptive mother, Patrick Glavin’s widow, Mary Glavin, née Flannery, and her brother, a cobbler named John Flannery. There was another Flannery sibling named Michael. The Flannery brothers appeared in newspaper police blotters for drinking, fighting, and loitering. Marion and Mary did not live with them long, and found a home of their own in Griffintown, not far from her father’s forge.

John Gordon, still on Shannon Street, had remarried and embarked on a second family with his young wife, Jane. It was a fresh start for John. He even named two of their offspring after the lost children from his first family: William and Jessie. Walking to school or to shops, Marion and little Mary passed by John’s house, inhabited by his new family, and his forge, still with its crowd of men in the yard.

In 1879, little Mary, now nineteen, married a boy from the neighborhood named Con Maguire. Con had grown up on Shannon Street, apprenticed as a printer, and was working as a compositor for the Catholic weekly the True Witness. A star player on the champion Shamrocks lacrosse team, Con was a local celebrity in Griffintown.

Marion, now forty with an empty nest, also married. Her new husband was an Irish Catholic widower and retired moulder named Peter Gahan. Con Maguire was Marion’s witness at the wedding.

During Marion’s wretched years in her plank cabin, her youngest sister, Jane had married Frederick Meyers, the head pressman at the Montreal Gazette. Marion’s family were now able to help her, or at least her children. In 1887, Con got a job as a proofreader and compositor at the Gazette, where he worked for the next fifty years, eventually becoming the paper’s night editor.

John Gordon died in the spring of 1895. He was ninety-two. He left his business to his youngest son, William, who also inherited his uncle Alexander’s business manufacturing scales. With the stubborn old man gone, William and his mother were finally able to move to a better neighborhood, on a leafy street more appropriate to their status as bourgois rentiers.

Later that year, Marion and Peter moved into a five room flat in one of John Gordon’s buildings on Shannon Street. At last Marion was allowed to come home, when it was no longer fit for her father’s inheritors.

* * *

We know one fact: that Marion Gordon was unmarried and pregnant in 1861. It’s not clear how this had happened. We can’t be sure her child was even Michael’s. The mystery behind the family story, once solved, just begets more mysteries.

Something else that is known: There are two ways to shape metal. In a blacksmith’s forge, the metal is heated until it is pliable. It still requires force to make the metal longer, or thinner or wider, or to move the metal in a specific direction. In a foundry, the iron is turned to molten liquid, and poured, filling the mold of the desired shape, and allowed it to solidify before it is broken free of its mold.

Marion died in 1899. She is buried in Catholic ground, with the Glavins, the Flannerys, and Michael Maloney.

For a time Mary and Con occupied Marion’s old flat. The Maguires had moved away a few times, but kept returning to the old neighborhood, until they too moved out of Griffintown for good.

In 1900, the Gordon house and the duplex flats on Shannon Street were put up for sale by Marion’s daughter Mary. Marion’s daughter was left the sole owner of her grandfather’s buildings in Griffintown.

Marion’s birthright reclaimed from John Gordon, once sold, was left to decay. In the decades that followed, the neighborhood became slum, then industrial wasteland. John Gordon’s workshop and his flats stood on Shannon Street until the 1970s. They had become flophouses and were eventually razed.

Wonderfully detailed social history! You squeeze so much personality from every bit of it.

Poor Marion! I can just see her family holding it over her head - "See what happens when you marry against your father's wishes? You made your bed - now lie in it."

What happened to Marion's brother William who inherited their father's property? How did Marion end up with the property?