The family of my great-great grandmother, Aurélie Gagnon, were newcomers to the Gaspé, but had deep roots in Québec, extending back to the first white people in North America.

Aurélie’s mother, Césarie Berubé, was from one of the original families in Bas St. Laurent, the land across the river from Québec City. Damien Berubé, a mason from Roquefort, France, arrived in New France in 1671, married Jeanne Savonnet, a fille du roi, in 1679, and settled in Rivière-Ouelle.

Aurélie’s father’s family, the Gagnons, were descended from Jean Gagnon dit Belzile, one of three Gagnon brothers from Tourouvre, Normandy, who emigrated to New France with the Company of One Hundred, a group of master carpenters, masons, and other craftsmen, contracted by Robert Giffard in 1634 to establish the Beauport colony in what is now Québec City. They operated a store in the lower town of Québec in the 1640s, and at least one of the Gagnons crossed the river to Rivière-Ouelle. Gagnons and Berubés would go on to farm in Bas St. Laurent for the next three centuries. A handful of habitants of Rivière-Ouelle, including Damien Berubé and Jean Gagnon, made a decisive contribution in the defense of Québec in the war of 1690 against Admiral Phips, who set out in October to attack the city with 2,000 men and 32 ships. On his way up the St. Lawrence River, Phips decided to loot a few villages, including Rivière-Ouelle. A few dozen Canadian settlers stood waiting on the shore, hidden by forest of fir trees.

The militia, led by the parish priest, Father Francheville, was ready when the English pulled oars and attempted to disembark. They were met by a hail of bullets through the trees. The English rushed back to their boats in panic. Rivière-Ouelle was saved, and the severely weakened fleet was ultimately repelled by the French at Québec.

In 1856, Edouard Gagnon was living up the coast from Rimouski in St. Octave de Metis. Césarie Berubé made the journey from Rivière-Ouelle to marry him. Edouard’s mother Lucie was born a Berubé. The Gagnons in Rivière-Ouelle frequently married their third cousins, however neither the parish record nor the notarized marriage contract mention any required dispensation for kinship. Two weeks later, Edouard closed on a piece of land in the bush belonging to John MacNider, in what is now Baie des Sables. John MacNider was a Scottish immigrant who had arrived in Canada after the Conquest. MacNider acquired the seigneurie, having purchased the land from descendants of the original 17th century seigneur of New France.

Edouard cleared the land himself. His obituary noted the bravery of Edouard, striking out into the bush and felling the first tree for a farm that would support him as well as his wife, Césarie Berubé, and their twelve children. The Gagnons were deeply religious. Edouard’s obit also lauded him for raising such pious children, which counted among them a priest and two nuns.

Their eldest son, Augustin, was ordained and made curé of Port Daniel, then an impoverished fishing village on the far side of the Gaspé coast.

This son must have been the pride of the Gagnons. At the ages of 54 and 51, Edouard and Césarie decided to start over, leaving the farm to their second son Joseph, now married with a small daughter, and setting out for Port Daniel with their remaining children, to live in the parish of their adored first born, Augustin.

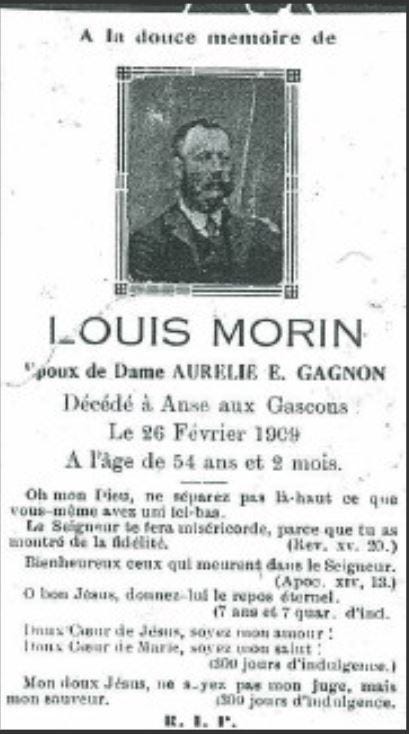

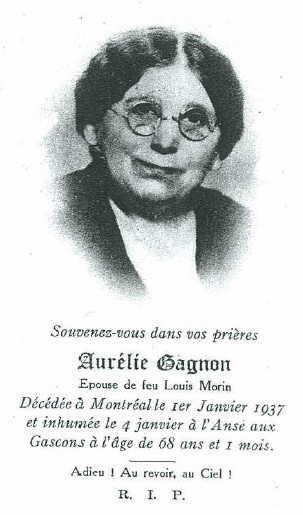

Augustin’s little sister Marie-Euphémie, “Aurélie,” was the seventh of the Gagnon’s twelve children and the fourth daughter. She was a teenaged schoolteacher in Port Daniel when she married Louis Morin, a 32-year-old farmer from the same town. According to family legend, Louis called on the Gagnons one day in 1885 and the purpose of his visit was a request to court one of the Gagnon girls. Edouard and Césarie did not know which girl Louis had in mind among the three grown daughters at home (28-year-old Elizabeth had married). The Gagnons thought he was interested in 22-year-old Odile, or 20-year-old Lumina, but Louis said he wanted Aurélie, “la petite.” Family legend was that Aurélie was only 15 or 16 when she married Louis in the spring of 1886, but she was in fact 18.

Louis was the eldest son of Louis Morin père, a farmer and fisherman, and Angélique Chapados, who, like her husband, was a pasbéya with deep roots in the communities along the shore of the Baie des Chaleurs going back two hundred years, and was in fact his second cousin via their connection to the Duguay family.

The older girls became nuns. Odile taking the name Sainte Monique, and Lumina taking the name Sainte Perpétue. They joined the order of the Sisters of Charity, otherwise known as the Grey Nuns.

Aurélie and Louis had fifteen children, including two sets of twins. Aurélie and Louis were imaginative- some of the children had names more commonly found in romantic French novels of the period than an isolated fishing village: Marie Elise (b. 1887), twins François-Xavier and Marie Louise Anne (b. 1888), Édouard Augustin (b. 1890), Marie Agnès (b. 1891), David (b. 1893), Marie Alma (b. 1895), Louis Rodolphe (b. 1896), Joseph Ludger (b. 1899), twins Angeline and Emelda (b. 1900), Théophile (b. 1902), Joseph Arthur (b. 1904), Léo (b. 1906).

The youngest, Lumina, (b. 1908) no doubt named for Aurélie’s older sister, was for her English-speaking young relatives beloved “Aunt Minnie.”

Louis died in 1909, leaving Aurélie, then just 40, a widow with many young children. The Morins were however modestly well-off and the Gagnons had by that time acquired the postal concession in Port Daniel.

Aurélie served as the town’s postmaster until sometime in the 1920s when she lost the post office, a political sinecure, due to a change in the local political party in power.

Césarie also died that year, shortly before her granddaughter Agnès’s wedding to George Smith. The family returned to Baie des Sables to bury her.

The Baie des Chaleurs was not a place people stayed. Farming was hard, and for the landless, fishing was a way to stay mired in poverty. Widowed and watching her children depart one by one, there were fewer and fewer reasons for her to stay. Aurélie eventually left Port Daniel and went to live among her children in Montreal. She was forever the widow of her beloved Louis. Her grandchildren never saw in anything but a black dress down to her ankles.