1864

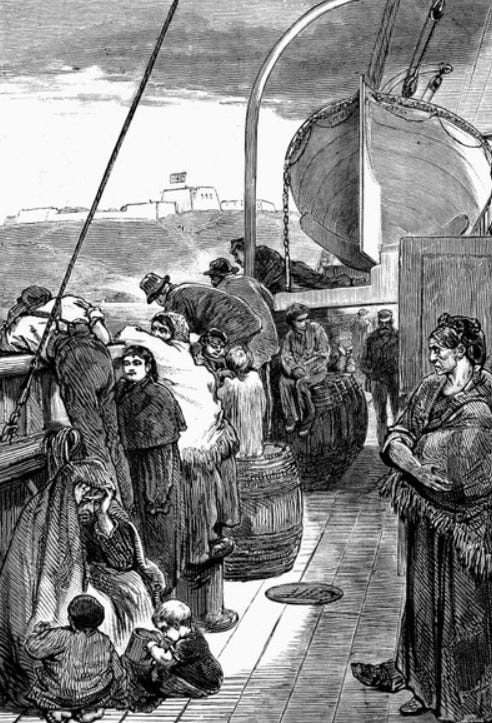

John and Catherine Maguire sell their shop and pub in Omagh, County Tyrone. It’s all for sale— the inventory, counters, gas fittings, lease, and license. They are going to try their luck in America.

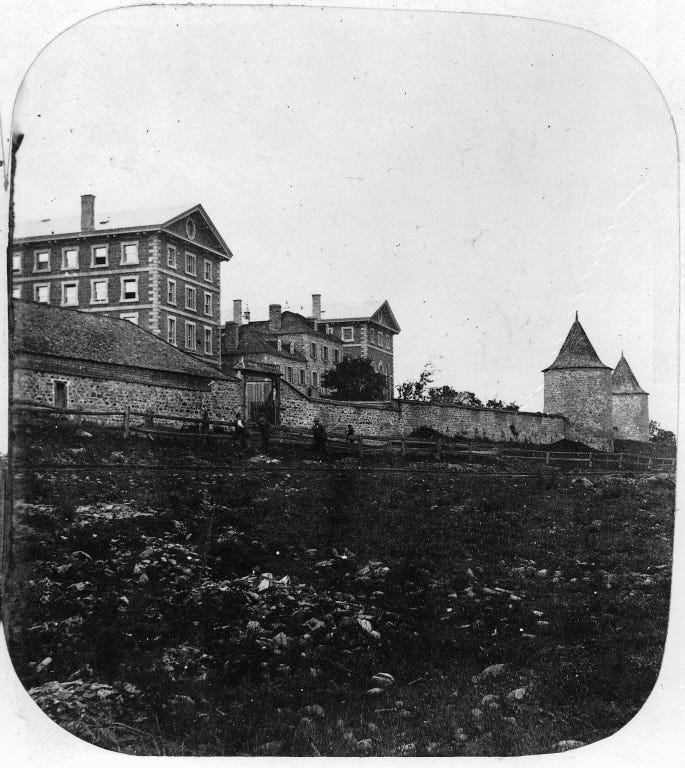

Emigrants from Omagh leave from Derry. The Derry ships bound for America follow the shoreline around the tip of Inishowen and then into the open sea. Families left behind by the emigrants light bonfires along the beach, which can be seen from the ships.

Ten-year-old Con Maguire and his brothers run from one side of the ship’s deck to the other. The starboard side is the black unknown. From the port side, they see lights.

No one has journeyed from Omagh to see them off, but Con believes one of the fires is for him. Like his father, John, Con moves through the world believing he matters. Con watches the shore and asks John which light is his.

There are four Maguire brothers: Con, Hugh, a year younger and inseparable from Con, and then Andrew, the odd one out, two years younger than Hugh. Their little brother, John, just five years old, runs along behind and does not yet register that he doesn’t count. Hugh is content to be Con’s follower. Not Andrew.

Andrew isn’t Con’s brother by blood. Andrew was born to Frank Maguire and Rose McGolrick. There was no church record to prove whether Frank and Rose were married or not. If they were not married, someone stayed the hand of the priest who did not add the word bastard next to Andrew’s name in the registry, as was the custom then.

After Andrew’s birth, the names of Frank and Rose will never appear together again. It is possible that Rose died and the Maguires have taken in the motherless child. But a woman named Rose McGolrick will marry another man in Omagh years later. There are a few men named Frank Maguire in Omagh and the surrounding country. There is no record of their claim on Andrew and he could be the child of any of them.

In the year of Andrew’s birth, Con’s parents had a baby girl they named Catherine, who did not live very long. Andrew may be less an orphan than a gift child, a boy the same age who could try to replace the little girl they lost. All we know for certain is that Andrew is now about seven, John and Catherine are taking him to Canada with them, and will consider him their child ever after.

1865

John Maguire opens a grocery and a tavern on a busy street in Griffintown. In the spring, the St. Lawrence River overflows its banks, flooding the low lying streets and destroying his shop. John makes fruitless demands that the city compensate him for his losses. He cannot pay his gas bill. He assaults an employee of the New City Gas Company who comes to turn off the gas. John is fined $50, levied by duress, meaning bailiffs come to their home and take furniture, clothes, even the sheets off their beds.

Con was six the first time he saw his father go bankrupt, back in Omagh. Now, scarcely more than a year in Montreal, John must start over again. He sublets a smaller shop in a less desirable street. He offers poorer quality produce to poorer customers because he’s been cut off from the best wholesalers. That shop also fails.

1867

John gets a job as a clerk for the Grand Trunk Railway. John trades out of the family’s flat when he can get his hands on goods to sell. These goods are even worse. John sets sums for Con and has him count inventory, half rotten pears on a blanket. He tells Con he must always watch for fingers on a shop scale and never quit until he wins.

Hugh sits quietly next to Con and takes in the lesson. But ten-year-old Andrew never listens to these sermonettes. He is off running in the street and brought home by the ear by some storeman for stealing an apple off a pushcart. He is caught drinking liquor with some big boys and beaten by his father with a belt. Andrew tells John that he is not his father.

1868

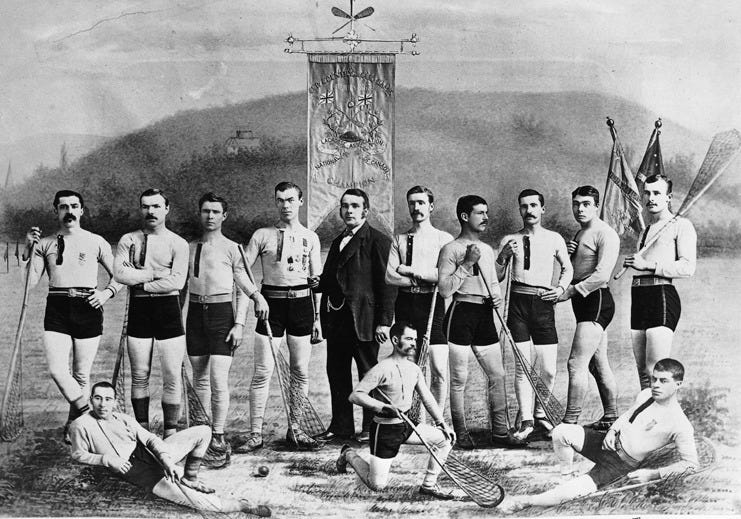

Con Maguire can run faster than anyone in Griffintown. He can outrun friends and enemies, even his father with his belt. As a little boy in Ireland he played a game called hurling. It’s the fastest and scrappiest game there is. In Canada, there is a game called lacrosse, so named for the stick that the French think looks like a bishop’s crosier. Lacrosse looks easier than hurling. The stick has a net. You don’t have to balance or bounce the ball off the hurley.

Lacrosse is a game for savages, they say. Englishmen have created new rules so that civilized gentlemen may play. Con learns that the Englishmen ban native people from their teams. No Irish play on their teams, either. When native men form their own teams to play the Englishmen’s version of their own game, the Englishmen will form a league and ban the native teams.

The parish priest finds a field for the Griffintown boys to play lacrosse. Father O’Dowd believes in sports as a diversion from other, less wholesome activities. Con doesn’t have time for whatever is going on in the street. Apprenticed to a printer, he is already a working man at fourteen. He works in a basement in winter and his first job is to thaw the frozen ink and run with it to the press while it is still warm. His fingers are black and white from ink and grease. The ink under his fingernails cannot be scrubbed away.

The lure of lacrosse is too great for Con not to join in, if only to remind the other boys that he can run faster than them, throw farther and straighter. He reminds Hugh of this fact every match. Andrew doesn’t care to play.

Griffintown boys are on the lacrosse field every free day they get. The Englishmen say they play like the savages.

Father O’Dowd convinces a group of Irish-born businessmen to sponsor a lacrosse club. The team finds a field at Priest's Farm. They call themselves the Shamrocks. They start defeating the Englishmen’s teams.

Fifteen-year-old Con joins the Shamrocks as the goalkeeper. The adults soon realize how fast he is. He is moved to center field.

1872

John Maguire is dead at the age of forty-two. Con, eighteen, is now the family’s main wage-earner. Hugh follows him into the printer’s trade. Con, sharp-eyed and literate, gets promoted to typesetter, leaving younger Hugh to run the flywheel and work the treadle of the platen jobber, from which pours sheet after sheet of Con’s composing.

Con proofs the backwards typeset as fluidly as he reads. Con is as proud of his work as if he himself had written the editorials and the eye-catching advertising copy. He consumes all printed matter: Newspapers, illustrated weeklies, labels on packing crates. Con loves the calm of the Saint Patrick’s Institute reading room. He devours poetry and Irish history. His head is filled with printed language. He writes poems in his head as he arranges tiny metal letters on his composing stick. The ink stains fade.

The two youngest children, Frank and James, born in Canada, scarcely remember John. Con has become the man of the house who metes out discipline and passes on John’s wisdom to the little boys.

Andrew is not an apprentice at anything, at least not for long. Paying work runs through his hands like water.

1875

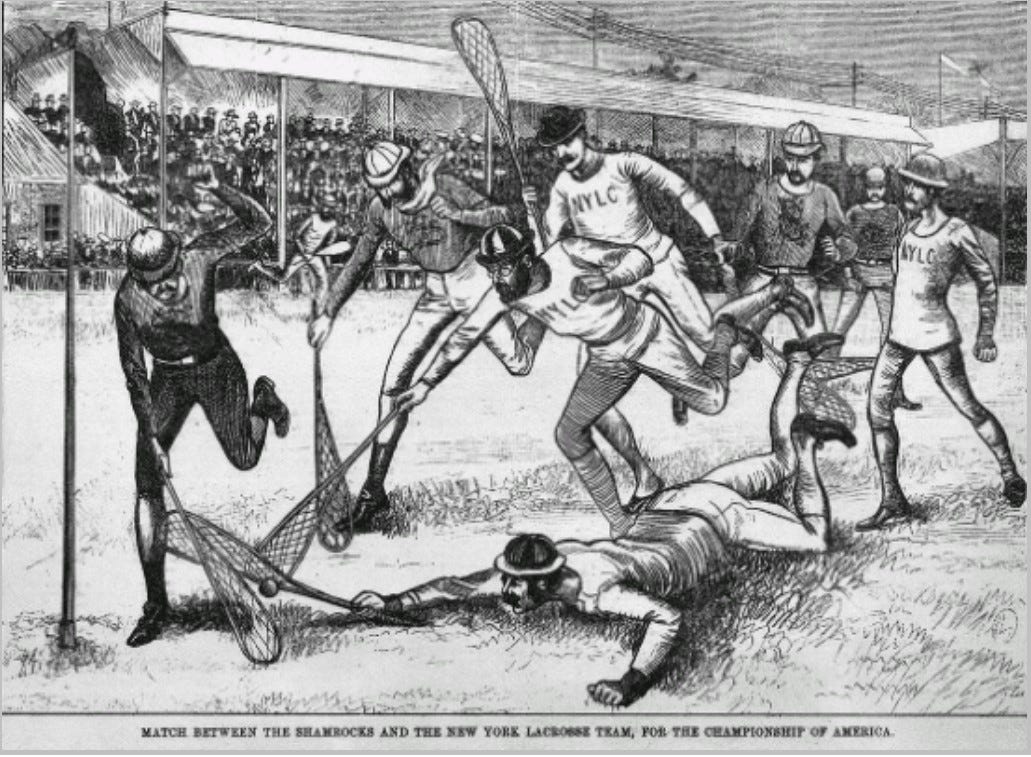

The Shamrocks’ Griffintown fans are not genteel spectators. They don’t follow the custom of clapping politely when the opposing team scores a goal. They holler loudly when their team does. They are not gracious when the Shamrocks lose. It’s not just a game to them. Victory could level the playing field, if just for a Saturday afternoon.

1879

From the Montreal Gazette, January 3rd:

HOW SOME CELEBRATED NEW YEARS

Excessively DemonstrativeTwenty five celebrants of the festive occasion of New Year’s Eve and New Year’s Day paid their respects to his Honor the Recorder. The following is the record of names and the parts they respectively took in the festivities and the gifts they received from the Recorder:

…Andrew Maguire, drunk. 15 days hard labor, and $10 or 2 months besides for assaulting the police.

In April Con gets married. The other Maguire siblings are still living at home. All are wage earners, even sixteen-year-old Mary Agnes, who is learning to be a seamstress, even twelve-year-old Frank, who is working as a messenger boy. All except Andrew.

In July the Shamrocks play Toronto for Championship of the World. The Protestant press claims the Shamrocks lack the “science” and team spirit to win. When they do win, the Gazette accuses the Shamrocks of rough play.

1880

Con is a working as a proofreader and compositor at the True Witness and Catholic Chronicle. His boss, editor Martin Kirwan, newly arrived from Ireland, becomes a lacrosse enthusiast. He writes editorials defending the Shamrocks and their feral fans against the calumnies of the Protestant press.

The Montreal newspaper employees get lacrosse fever. All summer, the compositors and printers from the Star, the Gazette, the True Witness and other papers challenge each other to matches. As a member of the Shamrocks, Con cannot play.

Andrew is charged with loitering and fined $10, or one month. Catherine has yet to reach her boiling point with her son.

1884

The Shamrocks defeat the Toronto Lacrosse club with “as fine an exhibition of real lacrosse playing as has been seen on any field for years” the Gazette reports.

From the Gazette, January 25th:

RECORDER’S COURT

Andrew McGuire was charged by his mother with vagrancy, he refusing to work to support himself. He was fined $5 and costs, with the alternative of three months’ imprisonment.

1886

Con retires from lacrosse. He will be remembered by his opponents as one of the best and cleanest players of the game. To capitalize on his sports fame he has opened up a cigar parlor called Maguire’s Goal.

Con moves out of Griffintown. His family lives in a spacious flat above the cigar shop, which is located on the elegant Victoria Square. He referees Shamrock matches on the weekends.

Con is now working for the Gazette, the paper that once maligned the Shamrocks. Hand compositors have disappeared from the Gazette newsroom, once silent as a chapel and now busy with clacking hot type all night long. Con works until dawn editing and proofing news stories with a dozen Linotype operators under his watch.

The Shamrocks try to disassociate themselves from Griffintown and their rowdy and disruptive fans by moving to grounds far outside the city and raising ticket prices. The game slowly loses its mass appeal.

1887

Con’s brother Hugh, his shadow, dies at thirty-one.

1890

Andrew disappears from newspaper police blotters. He marries Mary Ryan. The next year they will have a little girl named Agnes.

1892

Con quits the Gazette and moves his family to Rutland, Vermont. After Con and his wife bury two of their children in Vermont they decide to return to Montreal, where Con picks up his life where he left off, working at the Gazette and co-managing the Shamrocks.

1894

Andrew dies of pneumonia at thirty-seven. He leaves behind little Agnes, who is taken in by Con and family. Agnes lives with them until she marries, through the deaths of Con’s own daughter, mother, and wife. Andrew has given the grieving Con a gift child.

Greatly indebted to the following sources:

Pinto, Barbara S., "Ain't Misbehavin': The Montreal Shamrock Lacrosse Club Fans, 1868 to 1884” (MA thesis, University of Western Ontario, 1990).

Barlow, John Matthew, "The House of the Irish: Irishness, History, and Memory in Griffintown, Montreal, 1868-2009,” Ph.D. thesis, Concordia University.

Montreal history at its mot granular. Good stuff!

Such a range of feelings arise from your vivid writing.