In the winter of 1688 my Morin ancestors were expelled from their village of Beaubassin, Nova Scotia. They walked into the wilderness taking only what they could carry. The exile of the Morins is an Acadian legend. But to know why they were banished begins with the village of Beaubassin—a story of a great earthworks, a village rebellion, a witch trial, and forbidden love.

The previous installment may be found here:

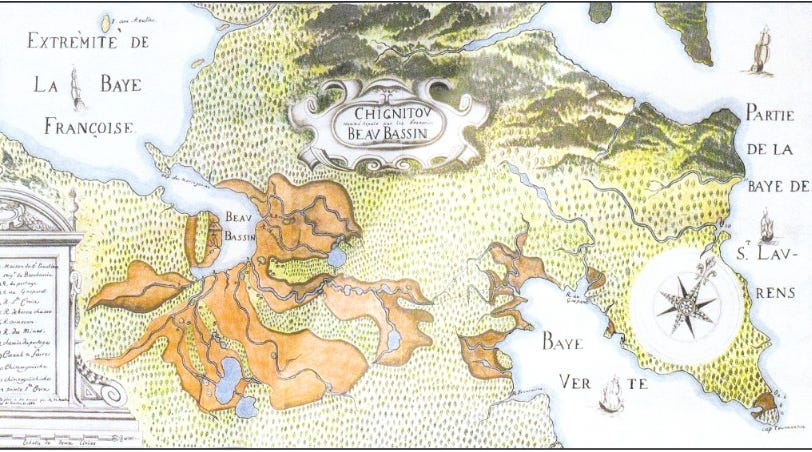

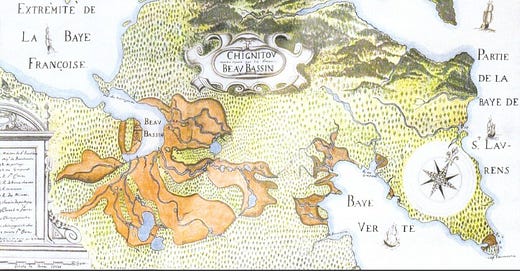

The story so far: In 1671 Jacques Bourgeois and his family establish a new settlement of Beaubassin, in the marshlands where Nova Scotia meets New Brunswick. They are soon joined by others seeking independence, including Pierre and Marie Morin. Everyone is engaged in back breaking work of draining the marshes. In 1676 Beaubassin is granted to Michel Le Neuf as his noble fiefdom. Le Neuf decides to impose his legal feudal right of the corvée, enforced labor on his behalf.

This installment introduces us to the village sex pest, Jean Campagna.

The villagers had rejected the corvée. Le Neuf continued to brood over how to clear the marsh.

He needed men to dig the new channels and the levees he’d been drawing. If he could not coerce men into working, he would have to pay them. He reviewed the male population of his domain and considered his options.

He ruled out the Mi’kmaw men. They were seasonal residents, and anyway did not see the need to work when they made a decent living off selling fur. They also did not see the point of the drainage project underway.1

Le Neuf needed his man Jacques Cochu to pilot the Saint Antoine. Le Neuf was not foolish enough to take on the strange, shifting waters of the bay himself. Cochu was not going to agree to demeaning spade work, even paid. Le Neuf knew better than to enlist the gunsmith Pertuis, his armorer, for the same reason. Le Neuf recruited some new men arriving from New France: Cottard, Labarre, Mignault, and Lagasse.

There was one man already in Beaubassin Le Neuf could hire: a homeless newcomer named Jean Campagna.

A native of Angoulême, Campagna had arrived in the new world in 1670 with Hector de Grandfontaine, the new Governor of Acadia headquartered in Fort Pentagoët, now Penobscot, Maine. A couple of years later, Grandfontaine sent Campagna alone to Port Royal, claiming there was not enough food in Pentagoët.2 At this time Pentagoët was rich on the fur trade and numbered at least 500 people. There may have been another reason to be rid of Campagna.

Campagna found his way to Beaubassin around 1675. He hired himself out to the villagers, claiming he knew how to build dykes and sluices in the Poitevin marshes back in France.3 He said he wanted to earn his own plot of land and build his own house, and worked extra time. Although a hard worker, Campagna was not well-liked. He drank and gambled, but always seemed to have money to lend, which he did ungraciously at predatory interest rates. He beefed with men and accosted young women— to proposition them or worse.

Trouble began before Campagna arrived in the village. Back when the Morins were still homesteading in Port Royal, Marie Morin had a visit from her baby sister Andrée then already living in Beaubassin and married to François Pellerin. One day, while walking in town, the sisters happened upon Jean Campagna molesting a young girl. Andrée told Campagna to stop. Campagna lunged at Andrée, who grabbed a large stick and smacked him hard. Campagna told Andrée she would regret what she had done.4 Andrée never forgot this incident, or the threat.

A few years later in Beaubassin François Pellerin announced to his family that he had found a man to help clear his land. The strange ploughman who entered the house was none other than Andrée’s old nemesis, Jean Campagna.

She was shocked. François heard her story just after it happened. How could he hire him?

Then François informed her Campagna would be living with them, on their property, under the same roof. Already hot, Andrée now boiled over. Was he mad? Campagna was a deviant and they had five little girls. Campagna had threatened his wife.

François roared that he was the head of the house. It was his decision. Suffit.

François, like all the village men, was working against the clock. From the time the first sluices, and dykes were built it took three years to even see something resembling a meadow. The first harvests from fields of cleared marsh could not feed everyone. The Pellerins had more land than most, but they had been blessed with only daughters. François had no sons to help him.

Still, François didn’t like raising his voice to his wife. In truth, he was a little afraid of Andrée. She was ferocious when provoked, and could hold a grudge to Judgment Day.

Andrée steered clear of Campagna, and kept a close eye on her girls. Then Campagna told François he wanted to marry their eldest, Huguette, and asked what would it take to arrange this. Andrée told her husband that there was no way Huguette was marrying some Poitevin degenerate. Still Campagna went around the village telling everyone he had arranged a marriage with the Pellerin girl.5 They would be married next month, next spring, next year, when he built his house.

Andrée moved quickly to arrange a union for the still underage Huguette with Pierre Mercier, and announced their betrothal to the village as soon as it was agreed. This did not stop Campagna from saying that Huguette was promised to him. Andrée made sure not to leave the girl alone in the house.

Marie Morin grew worried for her little sister. She and Andrée told their husbands that nothing good would come from having Campagna in their village. They told others, too.

Campagna soon caught the eye of Le Neuf. Campagna worked like a machine. He could dig more than three men. He talked too much, it was true, but he was not afraid of putting his back into it.

Pellerin and others were not happy sharing Campagna with Le Neuf, but they had little choice but to let him decide when he worked, and for whom. Le Neuf offered Campagna more money. Le Neuf gave him land in Beaubassin. Campagna told everyone he was going to build a house on it and get married.

Sometimes Campagna chose to work on his own land, building elaborate channels and berms in the wetland, believing his drainage design was superior to everyone else’s. He resented no one took his advice.

Jean-Aubin Mignault, one of Le Neuf’s new settlers, was planting his wheat in a poor patch of land that had only just been cleared the year before. The earth was still a sodden meadow. Campagna scoffed as he watched Mignault scatter his seeds, moving sidelong up and down his rows. That land’s too swampy, Campagna said. I know this from back in Poitou.

Mignault kept on planting. You need to drill, too, said Campagna, following behind. You need to drill, not broadcast, those seeds. Mignault ignored him. And then Campagna hit the raw spot: Your seeds are not going to yield anything.6 Mignault picked up a rake and waved it at Campagna, shouting at him to go away.

Mignault, still fuming, later told his neighbors what Campagna had said. Yes, Campagna was always butting in and thinks he knows better, they told him. I know, Mignault replied, but it’s like he wants us to fail.

Le Neuf knew Campagna got in petty quarrels but didn’t care—until there was a dust up with Pierre Godin, the Port Royal carpenter Le Neuf had hired to build his mill. Le Neuf didn’t ask what the argument was about. He went straight to the Pellerin’s house and gave Campagna a beating, threatening to run him through with a sword if he bothered his carpenter again.7

While he mulled over solutions to clearing the marsh, Le Neuf tried fulfill his responsibilities as seigneur.

Every time the English sailed up the bay, no one knew whether they were there to burn their homes and kill their animals, or sell them things. Le Neuf provided security for the village, with his man Pertuis maintaining an arsenal of seventy guns.

Le Neuf gave land to the Recollect missionaries to build a church. He and his family presided over weddings and burials and baptisms. He built a mill and an oven, although these were not exactly public works since as seigneur he had the right to charge for their use.

Le Neuf was not prepared for disaster, though, and the village was about to meet more than one.

Next: Death comes to the village

There is no record of any native labor on the earthworks, although it remains possible that Mi’kmaw men did take part. The rationale for why they would not work is entirely my own speculation.

Myriam Marsaud infered that Campagnard was an indentured servant of Grandfontaine and had come to the end of his contract. Myriam Marsaud, “L’étranger qui dérange : le procès de sorcellerie de Jean Campagnard : miroir d'une communauté acadienne, Beaubassin, 1685,” Thèse de maîtrise, Université de Moncton, 1993, p. 104.

My speculation, since he came from that region of France.

This incident and the ones that follow were all recorded in the depositions taken later, at the time of the Quebec prosecutor’s investigation. Gagnon, Jacques, and Jean-Pierre-Yves Pepin, Un sorcier en Acadie: Transcription annotée des minutes d'un procès et document contemporains 1684-1686, Les Éditions historiques et généalogiques Pepin.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid. The timeline for this incident is not entirely clear from the deposition. I have placed it before the events of 1678-1684.

Another great chapter. I like how you indicate the known from the informed speculation in the narrative. It makes for a convincing whole.

And the plot thickens...