In the winter of 1688 my Morin ancestors were expelled from their village of Beaubassin, Nova Scotia. They walked into the wilderness taking only what they could carry. The exile of the Morins is an Acadian legend. But to know why they were banished begins with the story of the village of Beaubassin.

The previous installment may be found here:

This installment recounts the tragic year of 1678-9.

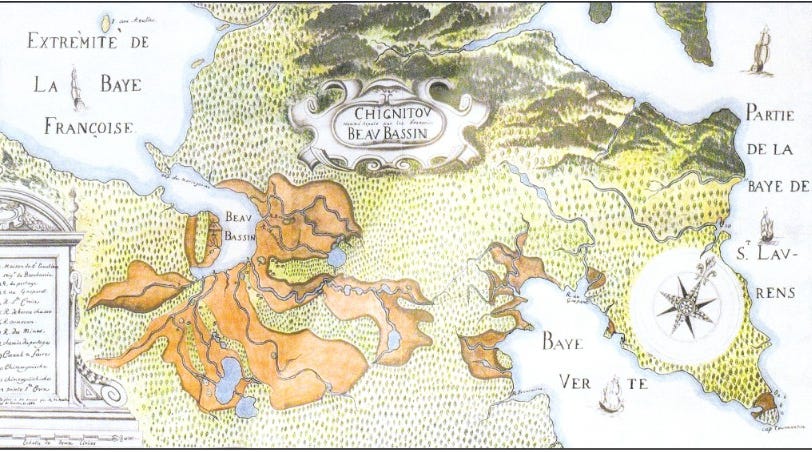

The story so far: In 1671 Jacques Bourgeois, his sons and sons-in-law, establish a new settlement of Beaubassin, in the marshlands where Nova Scotia meets New Brunswick. They are soon joined by others seeking independence, including Pierre and Marie Morin. Everyone is engaged in back breaking work of draining the marshes. Then, in 1676, Beaubassin is granted to Michel Le Neuf as his noble fiefdom. Le Neuf decides to impose his legal feudal right of the corvée, enforced labor on his behalf. The villagers resist. Le Neuf and the other villagers find a source of labor in the problematic Jean Campagna.

It was during that first year under Le Neuf that the people of Beaubassin became convinced that someone or something had brought them an ill omen. The first calamity was the most terrible.

Something from back in crowded towns in France followed them to remote Beaubassin. It must have come wrapped in wind or cloud, flying over open water and across mountains and forests, in an evil vapor pushing down into chimneys or seeping under doors.

Their Mi’kmaw neighbors told them that this evil had stalked Chignecto before, killing almost all of the people who had once hunted and fished in its marshes. That Chignecto, Acadia, and New France were vast graveyards. The sickness killed so ruthlessly and efficiently that there had been only a handful of dazed survivors to come down the Missaguash River to meet the French.

The illness claimed people quickly. They complained of headaches and nausea. Feverish, they took to their beds. Deep red rashes turned into angry blisters that spread everywhere. Soon the blisters filled with foul-smelling pus. Survivors were left with ugly scars and pitted skin.

Someone seen working in the fields in perfect health could be dead and buried before the week was out. Every night, it seemed, the villagers heard the sound of oars dipping in the water, and saw lamplight blinking in the thickets of the marsh, as Father Moreau headed to another house to say last rites. In one season, Beaubassin lost four heads of families and Jacques Bourgeois’s original comrades: Pierre Cyr, Jean Boudrot, François Pellerin, and Jacques’s own son Charles.1

News came that there was pox in Port Royal. If a person brought the sickness from there, who? Was it one of the Le Neuf family, always flitting back and forth to town on the Saint-Antoine? Was it one of the new men the seigneur had brought from New France? Had the disease been lurking in a healthy stranger to the village and leapt out when it was ready?

Andrée Pellerin lost her husband, François, and her eldest girl, Huguette, who had been affianced to Pierre Mercier. In their shared sorrow, Andrée and Pierre married each other, the mother substituting for her daughter. With her only son still a newborn baby, Andrée was grateful for a husband to manage the Pellerin land and cattle. And she did not have to evict Campagna. Offended by the rejection of his proposal to Huguette, he had already moved on to the Kessys.

As the village grieved, Le Neuf pressed the surviving men to acknowledge his feudal rights. They did not sign.

The men continued their work digging the marsh. As they turned over the muck in their grief, they started to see something else under their spades. Beneath layers of mud they saw tops of trees. They were walking on top of the remains of an ancient forest.2

There had been people here before, forests here before. Did this mean that God wanted the Acadians to be here? Were they just replacement bits of a vast machine? Perhaps Father Moreau knew the answer.

Le Neuf attended all the funerals. Once the widows of the old Bourgeois settlers remarried some of the new men, he thought that the village’s human center of gravity would have to shift. But when Le Neuf sought contracts, these new men now also refused to sign.

He could not discount the influence of Jacques Bourgeois, still alive and well in Port-Royal, still with two living sons in Beaubassin and observing all the goings-on there with interest. Le Neuf had no evidence of his meddling, but people talk.

Le Neuf tallied the resistance among the survivors: Two sons of Jacques Bourgeois. Two sons-in-law. Two brothers-in-law of one of these sons-in-law. One brother-in-law of the other son-in-law. This last was one of his own new men, Mignault…

Then the idea leapt forth in his mind. In-laws. It was the women! Ventrebleu, these women were the problem. They were stoking the resistance.

Le Neuf thought about two other résistants, unrelated to that group, Kessy and Morin. They were from Port-Royal, it’s true. But they were married to a pair of standout megères. And one of them had that Pellerin harpy as a sister.

Then again, it could just be that they were pig-headed Acadians. He had seen already how unreasonable they could be about so many things. There was no telling what any of these people were thinking. And sometimes they had the most extraordinary notions.

Cows were a perfect example. A cow was gold everywhere, but especially in Beaubassin, where there was so little being grown to eat. These Acadians were absurdly proud of their cattle— gamey, vile-tempered beasts with long, deadly twisted horns, and thick tawny hides like lions.3

One of Poirier’s cows went missing. The villagers combed the swamps looking for it. Days later, a carcass was found in the reeds, an arrow through its neck, stripped of its meat and hide. Le Neuf collected the men and told Pertuis to hand out weapons so that they could bring the criminals to justice. But the villagers refused. When he asked why, they shrugged.

Le Neuf learned that the savages “hunted” a cow now and then. Not very often, he was told. Just when they needed to. So these bumpkins didn’t do anything about it, they just grumbled.4 Unbelievable. Ignorant of property law as well as impertinent.

These people were maddening. Whatever the reason, this defiance must cease.

Le Neuf declared that all existing contracts in his domain were null and void. Still, the men of Beaubassin refused to sign.

Next: A Legal Remedy

Many thanks to Gary Tucker for his sublime photographs of the landscape surrounding the historic site of Beaubassin. If you wish to see more of his extraordinary work, or order a print, his website may be found here: https://garytuckerphoto.com/

We don’t know the exact date of their deaths, but their widows all remarried around 1678. We can guess that there was an outbreak or perhaps multiple outbreaks of smallpox or some other infectious disease, which may have claimed them. Witnesses at the time of the Campagna trial described “une année de grande maladie.”

Alex Monro, “On the Physical Features and Geology of Chignecto Isthmus” Bulletin Number V of the Natural History Society of New Brunswick, Feb. 3, 1885. https://voi.lib.unb.ca/en/node/1405

Since these would have been milk, meat, and draft cattle, I am imagining they were ancestors of the modern Poitevin maraichine. There were several breeds of cattle that were brought to Canada from Poitou and Normandy.

This was the attitude of Acadians in this part of the world in the next century, when there would have been more French and fewer native people. “Lettre de beauharnois et hocquart au Ministre,” 1745 septembre-octobre, COL C11A 83/fol.3-36v, 19-20, Archives Canada-France, LAC. Quoted in Jonah, A. M. L. . (2022). Revealing the History of the Isthmus of Chignecto: Toward Truth and Reconciliation. Journal of New Brunswick Studies Revue d’études Sur Le Nouveau-Brunswick, 14(1), 119–143. Retrieved from https://journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/JNBS/article/view/32890 Accessed April 20, 2025.

More good stuff. Hope you are planning a book out of this.

And the tension builds...