Longue-Pointe 1921: Pure Dreams of Solitary Birds

Sometimes the locked doors in the house of your family history can lead to glorious hidden gardens.

“Some stories are buried deep because they’re so hard to talk about. These are the stories that should never be lost.” - Barbara Tien

Big Irish families at the turn of the last century often had one child who didn’t fit the mold. This child was never expected to find his feet in life, and one or another sibling was always expected to look after him. This child was sometimes called a dreamer. It was a world with no diagnostic manuals. Whatever the trouble, it was never explained. If anyone asked, the answer was just say a prayer.

Hugh was born in Montreal in 1883, the third of eleven children. At the time of his birth, lacrosse was wildly popular spectator sport, and Hugh’s father, Con, was the star player of a champion team, the Montreal Shamrocks. Con had the drive and energy of ten men: He worked full time as a compositor, proofreader, and printer at the Montreal Gazette while playing for the Shamrocks. He also found the time to own a cigar store and serve as treasurer of his union local. As an old man in his eighties, Con would think nothing of taking a Sunday stroll to Lachine from his home in Outremont, a roundtrip of twenty miles. A self-educated Irish immigrant, Con had been forced to make his own way. He was tough on all his children, especially his sons, all of whom were expected to be athletes and achievers.

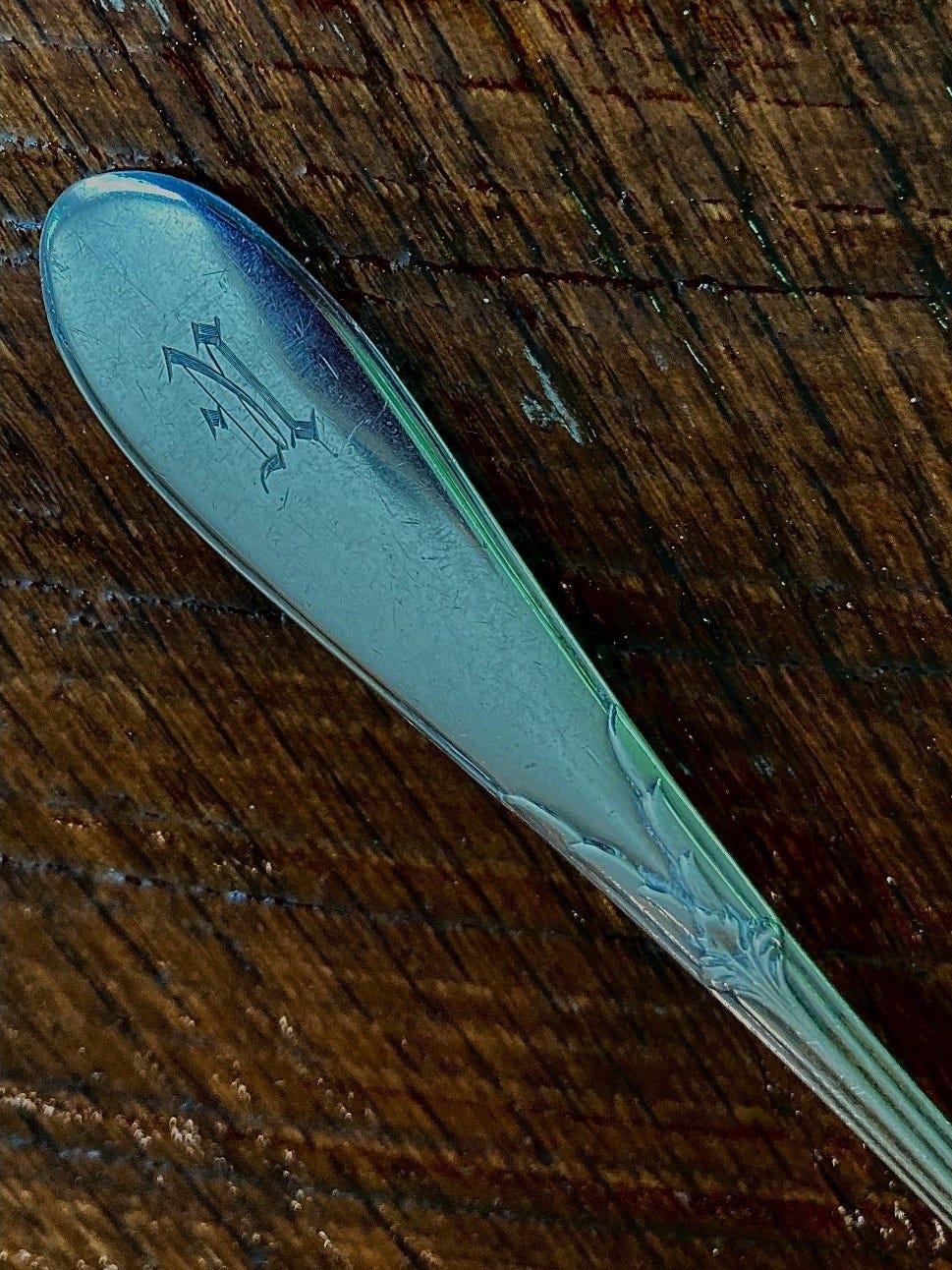

Hugh did not play sports, nor did he show any particular aptitude for his father’s other passions - the newspaper business, politics, and literature. There are no known surviving photographs of Hugh. Almost nothing is remembered about him. One could say that he left no mark on the world, except that marking was exactly his profession: Hugh was an engraver. He created small and beautiful things. Hugh’s designs were organic and flowing, in the elegant Victorian style he first knew as a young person.

For a time Hugh lived comfortably in the shadow of his older sister Mamie and older brother Michael within the imperium that was Con’s household. Then in 1892, on the day of Hugh’s ninth birthday, ten-year-old Michael died. Hugh lost three siblings and two uncles, including his godfather and namesake, before the age of eleven. At sixteen he would lose both his grandmothers, an aunt, and a baby sister, all within the space of a year. The restless Con’s apparent way to deal with grief was to move house. As a boy, Hugh was bounced in and out of half a dozen different homes.

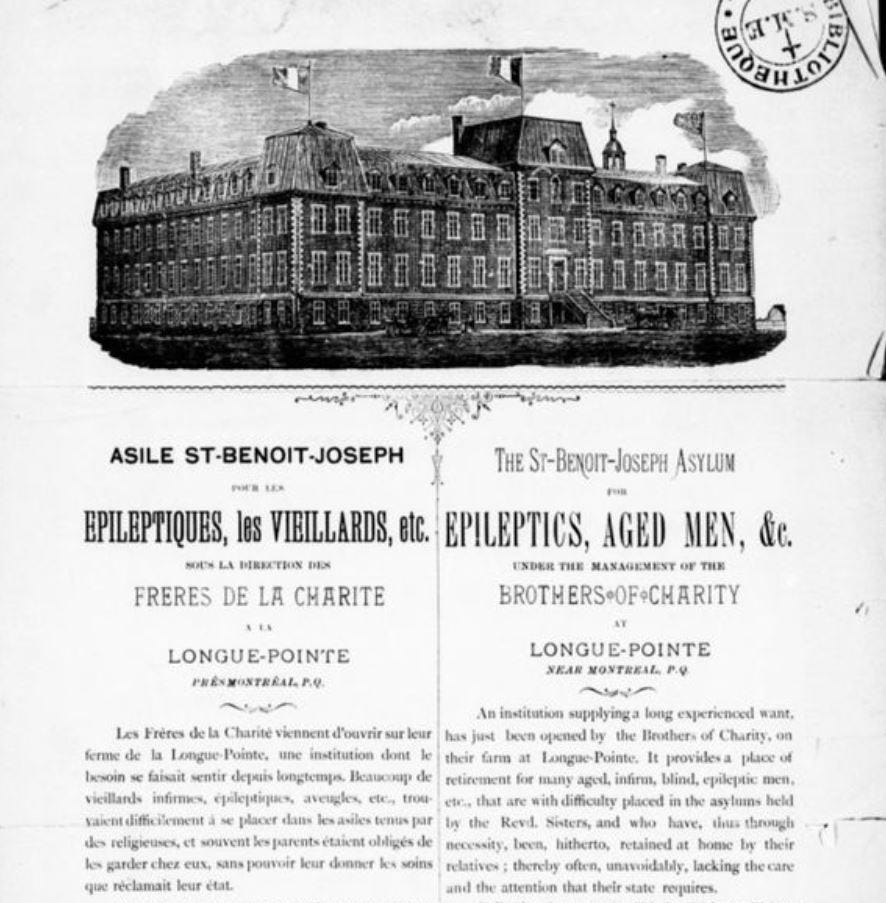

Con had apprenticed as a printer at fourteen, so it is not surprising that Hugh was also obliged to leave school and go to work at a young age. Hugh did not follow his father into the printing business, but trained in the adjacent trade of engraving. At some point in his early adulthood, Hugh was admitted to the Saint-Benoît-Joseph-Labre mental asylum at Longue-Pointe, in the far east end of Montreal, run by the Frères de la charité, a Belgian religious order that cared for elderly, disabled, alcoholic, and mentally ill men. The nature of Hugh’s troubles, and the reason for his commitment to a psychiatric hospital is not known. He is remembered as a shy, quiet man.

Saint-Benoît did not appear to be one of the nightmarish mental hospitals of this period. It catered to the well-off, and featured many bourgeois niceties not available in the nearby Saint-Jean-de-Dieu hospital complex, which had thousands of patients. Saint-Benoît cared for only a hundred or so men, and offered single rooms. Patients could bring a private nurse or attendant to live with them. The hospital also offered outdoor recreation: boating on the river, walks through the surrounding countryside, or excursions to the nearby Iles de Boucherville. The Mullin brothers, immigrants from Hugh’s family’s hometown in Ireland who had made their fortune in cold storage, were benefactors of the order. Their generous gift may have made the hospital accessible to less affluent people in Montreal’s Irish community.

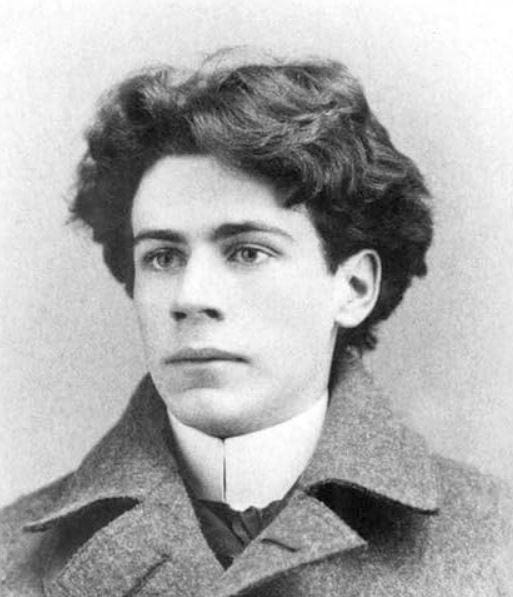

A number of years before Hugh’s arrival at Saint-Benoît, another young Irishman, about the same age as Hugh, had been committed to the hospital by his family when he first started exhibiting symptoms of schizophrenia. The boy was only nineteen, the typical age of first onset of this cruel disease. Unlike Hugh, he never left. His name was Emile Nelligan, and today he is known as Canada’s greatest French language poet.

Nelligan was also the child of an autocratic Irish immigrant father. David Nelligan was a self made man with no appreciation for French culture. Nelligan’s mother, Émilie Hudon, was Quebécoise. Nelligan’s early life is the story of Québec writ small: his father insisted that his family speak only English in the house, while his mother instilled in her son a love of French language and literature. The Nelligans lived near Hugh’s family in Outremont, which was an unusual Montreal neighborhood that had a mix of English and French-speaking residents.

Nelligan’s poetry shows the influence of the great French Symbolist and Parnassian poets, including Baudelaire, Rimbaud, and Verlaine. His best loved poems evoke mythical places and precious objects, Montreal streets, and the Canadian seasons, all of which convey the poet’s emotional state and paint an inner landscape of the mind. One of his best known works, “Ship of Gold” is taught in Canadian schools today. The poem gives a heart rending account of his psychological torment.

Que reste-t-il de lui dans sa tempête brève?

Qu'est devenu mon coeur, navire déserté?

Hélas! Il a sombré dans l'abîme du Rêve!

So, what has survived this flash of storm?

What about my heart, abandoned ship?

... O, still it sinks, deep in Dream's abyss. 1

One of his last poems, “Winter Evening,” has given Canadians the widely quoted line: Ah, comme la neige a neigé! (Oh how the snow has snowed).

Like Arthur Rimbaud, Nelligan was a precocious talent whose career was cut short. His entire body of work - over one hundred poems— was written between the ages of sixteen and nineteen. He was committed to Saint-Benoît in 1899. He never wrote another poem. Nelligan is only known to us today thanks to Eugène Seers, a priest with a literary interest, who began working with Nelligan's mother to gather and publish his collected poems in 1903.

A number of the Frères de la charité enjoyed literary conversations with Nelligan in his first years at the hospital. One of the brothers recalled that he had a sensitive, noble look.2 Over time, Nelligan's condition deteriorated. He read and discussed books less and less.

At some point before the end of the First World War, Hugh left the St. Benoit and found work in the printing business, working as an engraver for manufacturers of industrial stamps, tags, and knurls. He was living in Detroit working for the Superior Seal and Stamp Company (“only A-1 men need apply”) when he completed an American draft registration card in 1917.

In 1921, Hugh returned to Saint-Benoît. The family story was that he had become a postulant to the Frères de la charité. This is entirely plausible. After his prior stay, Hugh had become well enough to work and live in the world. Perhaps the care he had received from the brothers inspired him to help others. Upon his return he would have seen Nelligan again. Saint-Benoît was a very small hospital, so it is certain that Hugh and Nelligan knew each other.

Hugh did not however remain at Saint-Benoît as either a postulant or a patient. He eventually returned home. Around this time Nelligan also left the care of the brothers, but was instead moved to the nearby Saint-Jean-de-Dieu hospital, where he became one of many thousands of mentally ill people warehoused there. He remained in that facility to the end of his days, living that “slow, grey death” to quote one of the brothers. 3

Outside the hospital, Nelligan’s reputation grew. He eventually became Québec’s best known and best loved poet. He passed away in 1941, at the age of 61.

Saint-Jean-de-Dieu became a massive hospital complex with over 9,000 patients at its peak. Not long after Hugh came home for good, his younger brother Peter, a salesman married with four young children, had a breakdown and was committed to Saint-Jean-de-Dieu.

In 1961, Jean-Charles Pagé, a former psychiatric patient, published Les fous crient au secours! (The insane are shouting for help!) in which he denounced the conditions of his confinement at Saint-Jean-de-Dieu. The book was a best seller in Québec, and served as the catalyst for reform of the psychiatric system. It was too late for Peter, who died in the facility the very year Pagé’s book was published, at age 65.

Saint-Benoît was operated by the Frères de la charité as a psychiatric hospital until 1974, when it was taken over by the Québec Ministry of Health. It’s now a nursing home.

Hugh went home to live with his father and sister Mamie. He outlived them both. In old age he lived on alone in the flat they had all shared. He was a frequent guest at his brothers’ homes for Sunday dinner, where he is remembered as a calm and modest presence. He died in 1958, aged 75.

Hugh’s undiagnosed troubles, his delicate engraving, his gentle silences, bring to mind these lines from one of Nelligan’s poems:

Ainsi la vie humaine est un grand lac qui dort Plein sous le masque froid des ondes deployées

De blonds rêves décus, d’illusions noyées

Ou l’Espoir vainement mire ses astres d’or.

And so human life is a great sleeping lake—

Under the cold mask of unfurling waves, full

Of fair dreams broken, illusions drowned

Where Hope sets its sights in vain on its golden stars. 4

Special thanks to Dr. Mary Maguire for her memories of her uncles.

Oh, my goodness, I'm so honored to be mentioned. Deeply buried stories really are the important ones. Sometimes you have to dig gently to not damage them in the retelling.

Poignant. I looked into the poet Nelligan's Hudon genealogy and found several of our common ancestors -- Hudon, Sargent, Gagnon, Oullette lines. So much of history to bring to light. I can't let-go the image of this trapped and gifted poet. Is Hugh in your lines?