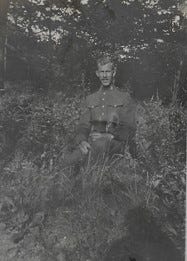

Conor Maguire was a twenty-six-year old clerk for the Smardon Shoe Company still living at home when he enlisted with the Duchess of Connaught’s Own Irish Rangers, on April 19, 1916, just days before the Easter Rising in Dublin.

Conor grew up in a home where the Irish national cause was an ever-present venous hum. Enlisting had to reconcile two conflicting loyalties: to Ireland and to the British Empire.

As soon as war was declared, the Irish party in British Parliament suspended its campaign for Home Rule and urged men in Ireland to enlist. (Conscripting the Irish was commonly understood as an “act of insanity” and was never imposed on Ireland). Irish organizations in Montreal, including the republican-leaning Ancient Order of Hibernians, pledged loyalty to Britain’s war effort.

By 1916, Canada’s volunteer forces had thinned with the growing casualty lists. To replace the losses overseas, the Canadian government allowed communities to raise their own battalions. With the conscription controversy in Ireland putting the loyalty of Irish Canadians into question, the Irish in Montreal decided to raise an Irish regiment for the Canadian Expeditionary Force.

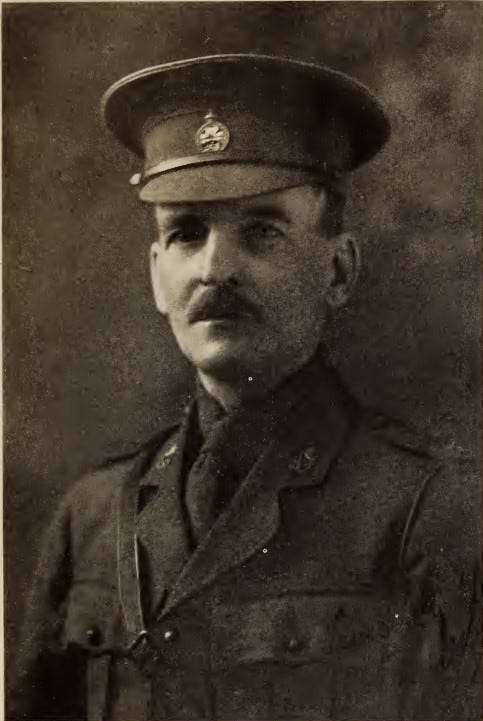

Harry “Flip” Trihey, a prominent Montreal lawyer, was named the Rangers’ commanding officer. Flip’s father, Tom, had played on the champion Shamrocks lacrosse team with Conor’s father, Con. Tom and Con were leading members of the Shamrock Athletic Association, which sponsored both its ice hockey and lacrosse teams. Flip had been a starting forward of the Shamrocks hockey team in 1899-1900, when it won back to back Stanley Cups.

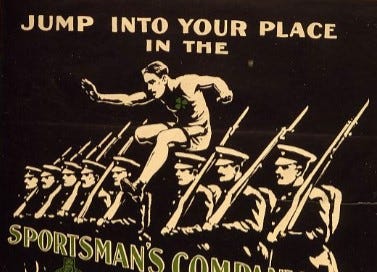

This would be a special “Sportsman’s Company” drawn from local lacrosse, track, and hockey enthusiasts, with Flip’s name prominent on all of the Rangers’ recruitment posters. The Shamrock Athletic Association endorsed the Rangers at the meeting of its board of directors on April 18th. Conor, a player on the Shamrocks lacrosse team like his father, signed up the very same day.

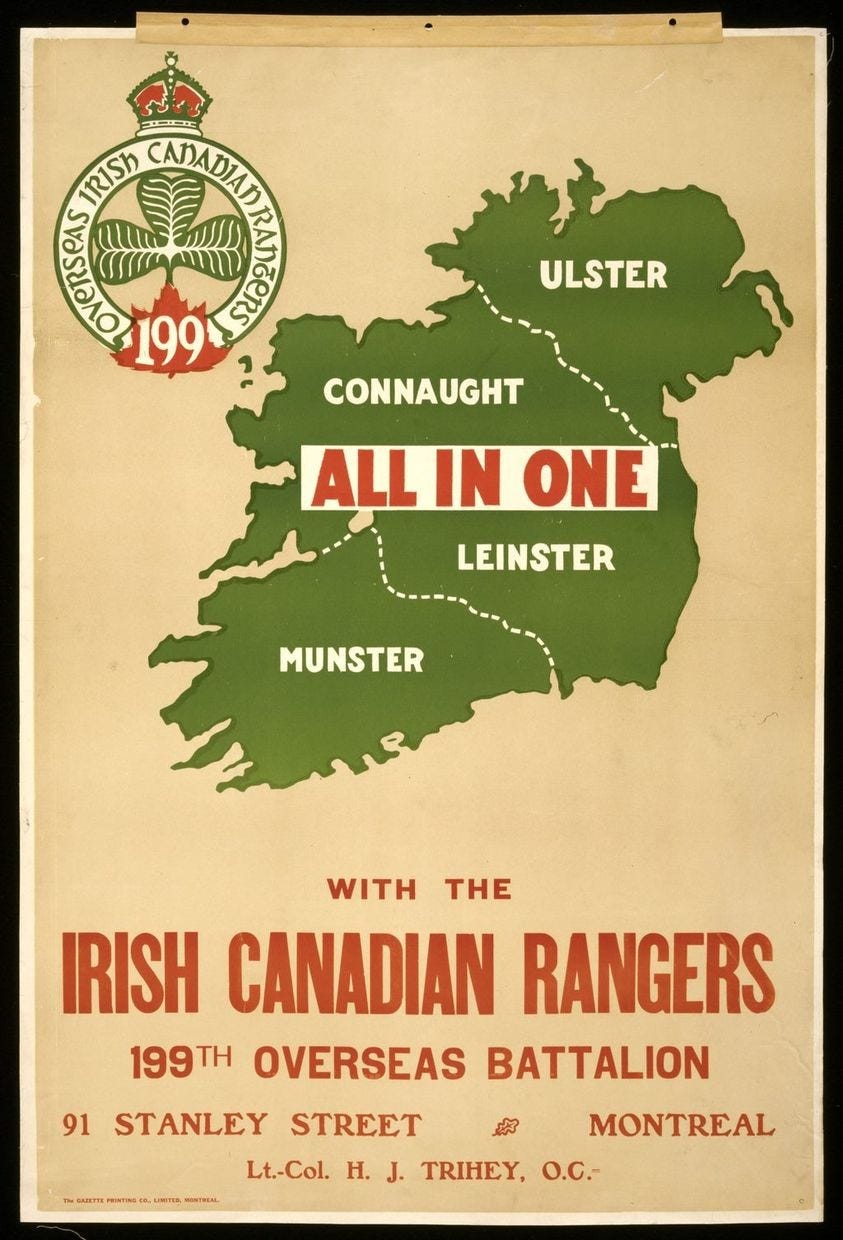

The Rangers were non-sectarian. The theme of the recruitment drive, and another feature of the Rangers’ brand, was unity among all Irishmen in Canada. A recruiting poster featured a map of Ireland, proclaiming “All in One.” Conor’s father Con clearly supported his enlisting with the Rangers. Con was the night editor of the Montreal Gazette, and the paper championed both the Rangers and the Irish Canadian commitment to the war effort. A Gazette editorial called the Rangers “the Canadian exemplification of this new United Ireland.” 1

Conor and his fellow recruits were fêted with parades, smokers, and evenings of musical entertainment throughout the spring of 1916. That summer the battalion held nightly rallies in Dominion Square to inspire men in the crowd to march up to the platform and join the ranks of the Rangers. It’s better than staying around poolrooms and bowling alleys. Rangers teams had won baseball games, football games, boxing matches. Just to show you what kind of crowd you will be with. Men back from France recounted grisly scenes of Germans bayonetting Canadian soldiers to barn doors. It was a fight for civilization, and the Anglo-Saxon race. A half dozen little girls were brought up to the platform to sing “God Save the King.” Step lively, and in bunches. Come up and I’ll tell you a funny story.2 The crowds were unmoved.

In July, mere weeks after the court martial and execution of the Rising’s seven leaders, a rally for Griffintown women was held opposite St. Ann’s Church. The Rangers’ regimental band played in the summer twilight. On a platform in the middle of the square, under an arc light, Irish Montrealer Chief Justice Charles Fitzpatrick and Montreal MP Charles Doherty gave fighting speeches. No man can better serve Ireland than by volunteering to serve at the front, Doherty told the women.3 Someone yelled: Why don’t they give us a little freedom in Ireland? 4 Doherty told them the British would see to it they would get fair play. The women jeered and booed.

When Conor finally shipped out to Europe later that year, the ranks of the Rangers had finally been filled with an assortment of men, not all of them Irish.5

In August the Rangers acquired a patron. The wife of Canada’s Governor General, Prince Arthur, third son of Queen Victoria, and Duke of Connaught. Margaret Louise, Duchess of Connaught, was named its colonel-in-chief. For its short-lived existence, the 199th battalion was known as the “Duchess of Connaught’s Irish Canadian Rangers.”

The Rangers left Canada in December, arriving in Liverpool after spending Christmas at sea. Before heading to the front they made a two-month tour of Ireland to attract other Irish recruits to “take the King’s shilling.” Conor had been the first Maguire to set foot on Irish soil since his family left in 1864. The regiment paraded in front of cheering crowds. In Belfast, workers poured out of the shipyards and mills to follow the Rangers to Donegal Square to the sound of the Rangers’ brass band.

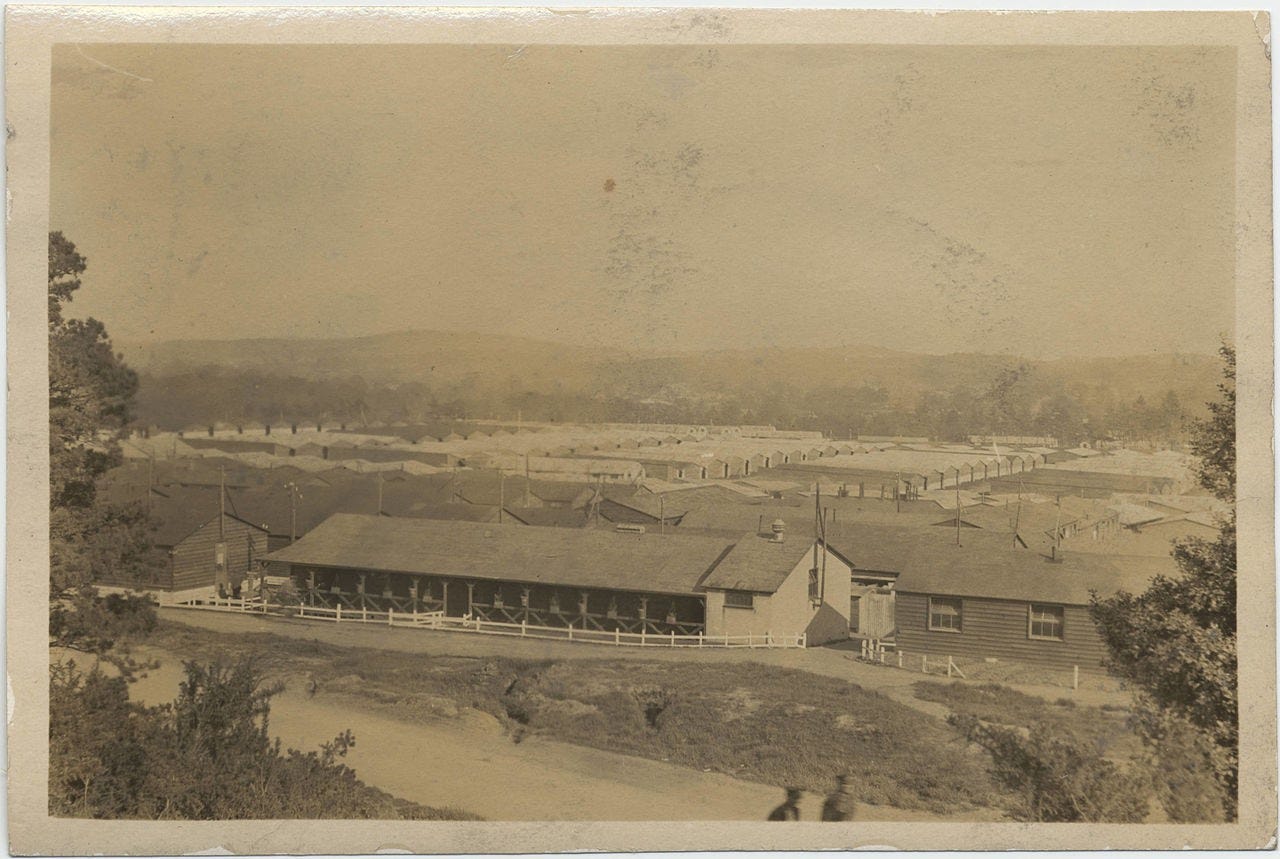

Shortly after the Irish tour, the Duchess died of influenza. No sooner had they arrived at Camp Witley in Surrey than Trihey was informed that the battalion would be disbanded and used for reinforcements. No real reason was given. We can imagine the unease surrounding what several hundred colonial Irishmen with guns could do.

Trihey, enraged, resigned his commission and returned to Montreal. Later that year, in the midst of the Canadian conscription debate, he would publish a stinging letter to the New York Daily Post.

The Irish Canadian ….wonders if the conscripting of 100,000 more Canadians would still be necessary if the 150,000 men comprising the English army in Ireland were sent to fight in France.6

Trihey only escaped trial for sedition due to the intervention of his old friend Charles Doherty. 7

Later that spring Conor was transferred to Shoreham, Sussex, where he was part of the 23rd reserve battalion, shipping to France with the Victoria Rifles in May, thereby missing the carnage at Vimy Ridge in April.

In July 1917, Canadian infantry near Lens, Pas de Calais, were making preparations for what would be the Battle of Hill 70. On July 26th, last orders were issued setting July 30th as the day of the attack, which was intended as a diversion from the Flanders Offensive. Heavy rains reduced the area to a swamp, however, preventing reconnaissance or wire cutting. The attack was postponed and bombardment continued into August, when the battle began.

Private Conor Maguire and other infantrymen were passing through a hellscape of deserted mine workings, slurries, slag heaps, and the rubble of French towns. On July 30th, Conor was walking through a village when a bombardment forced him to take cover in a cellar. He had the good luck to have the house fall on him. It probably saved his life. Conor was quickly dispatched to a hospital in Rouen. He missed the Battle of Hill 70, which claimed the lives of 1,500 Canadians, many to the newly invented mustard gas.

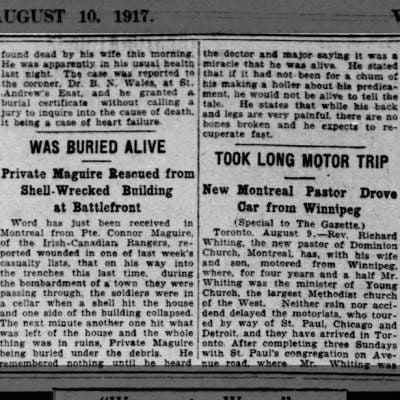

The Gazette told the tale of Conor’s rescue from the collapsed building. On that day, the paper also reported that Allied forces had conquered 1,200 yards in the Houtholst Forest in Flanders. The men returned to their trenches coated in thick slime, looking as though they had been “buried alive and dug out again.” Meanwhile, the Social and Personal page reported engagements, tea parties, and visits. Conor’s story appeared alongside an item about a Methodist pastor who drove to Winnipeg.

The news story claimed Conor wasn't badly hurt. In fact he spent the next five months in a military hospital with a broken back. He missed the battle of Passchendaele, which claimed a quarter million casualties, including the lives of 4,000 Canadian soldiers.

As Conor recovered, the possibility of a united Ireland under Home Rule disappeared with the election of Sinn Fein.

Soon after, the Canadian national parliamentary election decided the issue of conscription. Before the election campaign had begun, an anti-conscription protest in Montreal turned into a riot, with a mob breaking windows, looting, and assaulting soldiers. But when Canadians went to the polls that fall, the Irish of Griffintown had voted overwhelmingly for candidates supporting conscription, proving that Irish Canadians had finally become Canadians first.8

Harry Trihey returned to his law practice and raised a family in Westmount. The Maguire family remained friends with the Triheys for the next forty years.

Conor came home alive in May 1919, with all four limbs and a case of PTSD. For three years of his life, months of pain from his injuries, and the horror of trench warfare, he was paid $20 a month, which he sent home to his sister, Mamie.

Special thanks to Mary Burke Trapeni for the photographs of Conor Maguire, and to Dr. Mary Maguire for her memories of her uncle and the Trihey family.

Thanks also to Professor Matthew Barlow (https://matthewbarlow.net/about/) and his landmark history of Griffintown, “The House of the Irish.”

…And to the blog “last stand on zombie island” for the rich detail on the short history of the Rangers. https://laststandonzombieisland.com/2023/02/02/the-irish-rangers-of-montreal/

Montreal Gazette, April 14, 1916.

Montreal Gazette, July 24, 1916.

Montreal Star, July 28, 1916.

Montreal Gazette, July 28, 1916.

John Matthew Barlow, “The House of the Irish": Irishness, history, and memory in Griffintown, Montréal, 1868-2009, Ph.D. dissertation, Concordia University, 2009. p. 155.

Montreal Gazette July 3, 1917

Barlow, Matthew, “Scientific Aggression,” in Coast to Coast: Hockey in Canada to the Second World War, John Chi-Ki Wong, ed., University of Toronto Press, 2009. p. 46

Burns, Robin,"The Montreal Irish and the Great War," CCHA Historical Studies, 52(1985), pp. 67-81.

"was buried alive" next to "took a motor trip" is surreal...despite his wounds and PTSD, he made it out alive...shaking my head because what an awful yardstick is that! And Trihey facing sedition for pointing out the obvious...the ones who felt they were Canadian first because they supported conscription sounds like what one of my uncle once said when asked him about being French. He said he was American first. I can feel the questions beginning to surface...