New York 1953: Take Me To The Circus

Educated fleas

On the first week of fourth grade, the nun declared there were six girls too many in Patsy Casey’s classroom. It was true that Saint Augustine’s had a surfeit of girls in its elementary school. A wave of Italian immigrants had arrived in Montreal in the years after the war, some settling in Notre Dame de Grâce. Parochial school classrooms swelled with the new arrivals. The nuns, small town girls from Nova Scotia and the prairies, made a great show of not being able to pronounce their names.

The girls sat alert at their desks. They knew something was afoot when Sister Saint William did not start the day’s geography lesson. The fifth grade teacher arrived at the classroom door, and together the nuns counted off six pigtailed heads. “Off you go, girls,” said Sister Saint William. Patsy and the others followed Sister Saint Joseph down the corridor with apprehension. They weren’t in trouble, but Sister Saint Joseph was not pleased, so it wasn’t anything good.

They entered the fifth grade classroom and the nun directed them to take the six empty seats, desks crammed into a newly formed aisle by the radiator. The fifth grade girls stared. Patsy had been skipped a grade.

The next weeks and months were a nightmare. Taunts of baby and pantomimed thumb sucking. Feet quick as snakes, darted out from behind desks to trip her up as she headed past the rows of anonymous heads all bowed in fake prayer.

Patsy’s old classmates melted away from her. They never again invited her to join in hopscotch or jump rope with them in the schoolyard. She was now a fifth grader, and lost to them. The girls who were skipped with her were not her friends. If they were also miserable, they didn’t show it. Each girl was on her own island of unhappiness. Patsy walked to and from school with her sister Joan, parting from her at the classroom door.

The nuns were oblivious to her pain. She had been chosen to skip because she was a good student, so no teacher bothered to explain anything to her. If she could skip a grade, she could catch up. In Math, Patsy stared at the blackboard in mounting horror. There weren’t even any numbers, just x and y, and points plotted on graphs. In French, where Patsy had only started learning passé composé the year before, the chirpy little French nun named Sister St. Hippolyte was drilling them on the imperfect tense. Whenever the teacher threw out a question to the class, all the girls turned and stared expectantly at Patsy to see if she knew the answer. Why did you skip a grade? Because you think you’re smart. She slipped down in her seat, wishing the floor could conveniently rise like the tide and swallow her whole. If she was ever directly called on and didn’t know the answer, they would suck their teeth. For shame.

Relief came at the end of the year. Her grandfather was coming to live with them and there were not enough bedrooms. Patsy would be a weekday boarder at the Pensionnat du Saint Nom de Marie, located in the east end of the city. She could come home on the weekends and double up with her sisters in their bedroom the nights she was home.

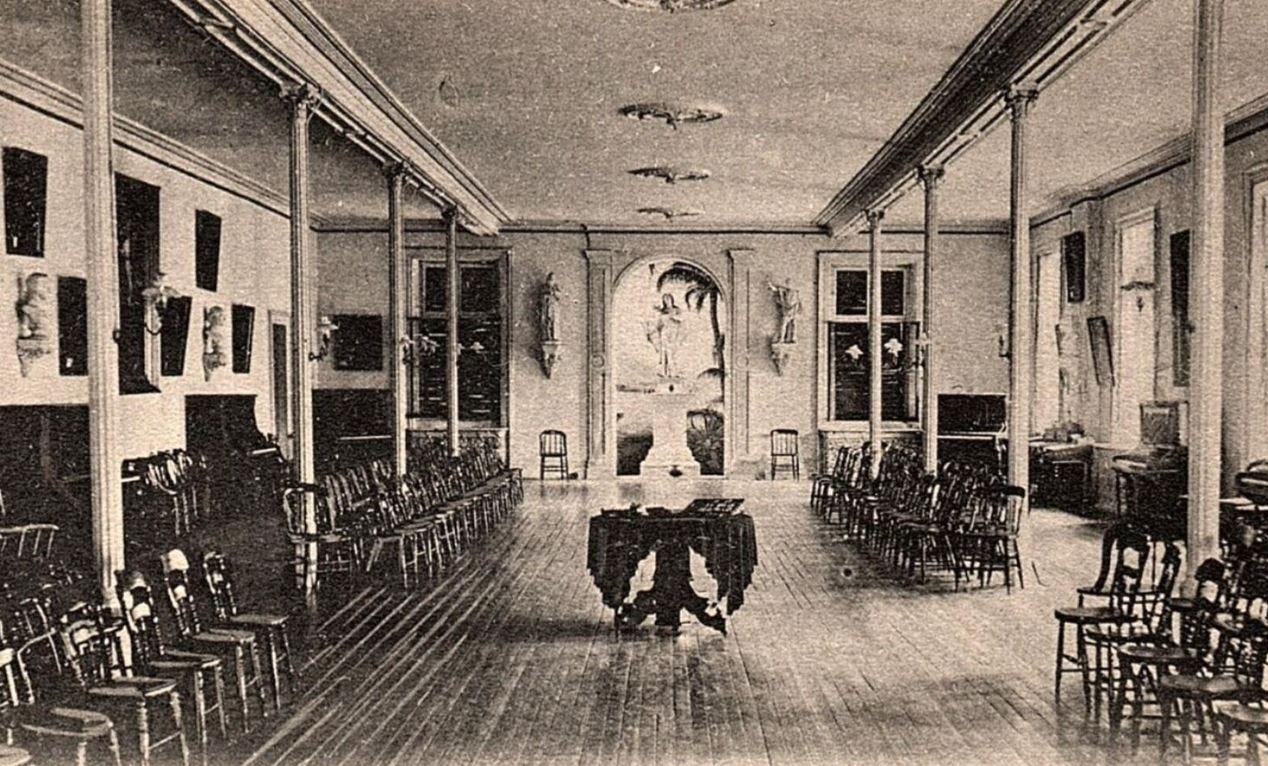

The convent school was equally lonely. She did not make friends with the other girls. From that first walk up the avenue to its front door, with its relentless rows of Ionic columns, Patsy knew she was in alien territory. The interior, all bare floors and uncushioned seats, was cold.

Once a week a nun would come into the dormitory to administer the white glove test. Mademoiselle… Kaw-seee. There was no need for any other words when her name was accompanied by an icy raised eyebrow, the smudged index finger held aloft for all to see. Sundays at home were sad, because of the pang of that impending endless ride on the streetcar all the way back to the convent on Sunday evening. Patrick, her father, made it easier by accompanying her, before making the long return journey by himself.

The next year, it was her younger sister Joan’s turn to board at the convent. Joan wept every Sunday night when she had to ride the streetcar back to Hochelaga with her father. But for Patsy, Joan’s torment meant she could come home and claim the empty bed. Back at school, most of her classmates had forgotten she’d skipped a grade, did not call her baby, or expect her to know all the answers. Still, she struggled to fit in.

Patrick must have had some extra empathy for Patsy, who, like him, was too young to be thrust out into the world.

She saw girls from school walk along Sherbrooke Street arm in arm, on their way to a matinee at the Empress, probably to see a movie featuring Patsy’s favorite star, the handsome Italian tenor Mario Lanza. Patsy was not invited because she couldn’t go. In Québec in those days, you had to be sixteen to be admitted to movie theatres. An October baby, Patsy was just fourteen at the beginning of her final year of high school.1 She had little in common with her older classmates, some of whom were sixteen and had boyfriends. Some of the boyfriends had cars. Some of the boyfriends with cars were old enough to drink. Weekend nights she stayed home.

Patsy finished high school at fifteen. Patrick must have had some extra empathy for Patsy, who, like him, was too young to be thrust out into the world. His mother decided he was a prodigy and insisted he skip a grade. Like Patsy, he was born in October and had also graduated at fifteen. Patrick had gone to university too young, and dropped out of school into the Great Depression. In between hunts for work he earned pocket money hustling pool and gambling. With little to look forward to but the next game, he explored the lowlife of the big city, in its pool halls, racetracks, nightclubs, and saloons. At the time, there was little to show for his early promise, it seemed, but some wasted years and false starts.

For Patsy, too, after running first out of the gate, the next years would be spent trying to figure out what to do next. Trying this and that, choosing and abandoning jobs, careers, and college majors. And so, in the summer of 1953, as a high school graduation present, Patrick invited her to join him on a business trip to New York City.

Patrick was the Canadian comptroller for RCA Victor, and his trip to New York was to visit RCA’s head office. They took the Montrealer into Grand Central. Patsy accompanied her father to RCA headquarters at 30 Rockfeller Plaza, and almost swooned when she rode the elevator with Eddie Fisher.

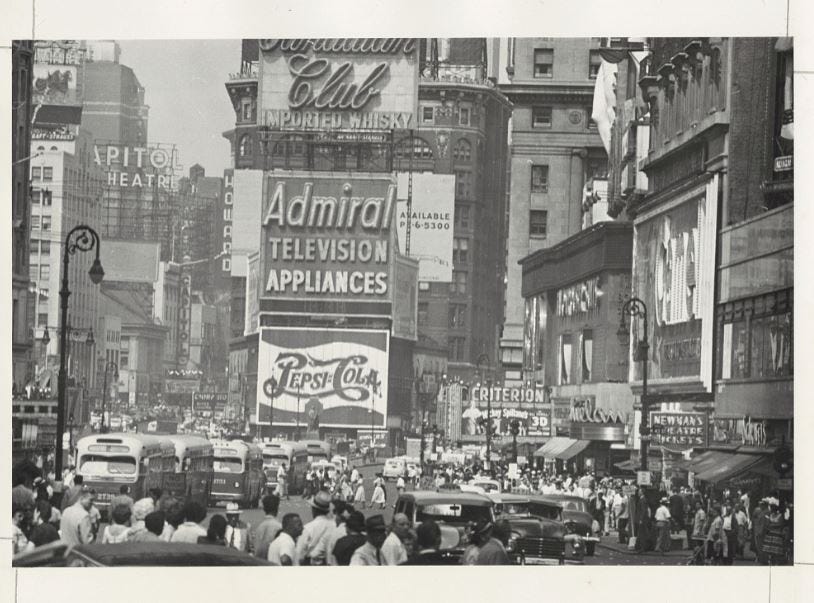

Once his meetings were concluded for the day, Patrick suggested a stroll to Times Square. He remembered his own visits to New York twenty five years before. They walked past addresses he remembered as speakeasies and jazz clubs. Patrick thought of the New York he had first seen as a young man, when he looked up at the steel teeth of the half-built Empire State Building outlined against the sky, and was invited to furtive games of street craps. He remembered too the desperate men on the street, wearing sandwich boards, selling scavenged items, or simply begging. The weather was fine, and it was a nice day to go out to Belmont or Aquaduct, but he knew that Patsy should see the city properly. She should visit Central Park or the Statue of Liberty.

Patsy had not seen anything like Midtown Manhattan. Her family did not yet own a television and she wasn’t allowed to go to the movies, so nothing had prepared her for the teeming crowds and pulsing traffic.

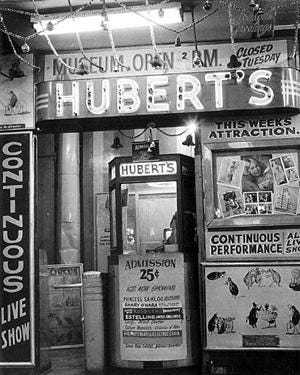

At Times Square, Patsy gaped at the neon signs and giant billboards, especially the Camel ad with the blowing smoke. On 42nd Street, they walked by what looked like a game arcade. The sign said Hubert’s Dime Museum. The posters in the windows advertised a freak show featuring a Snake Dancer, the Human Caterpillar, and a tattooed woman. This held no appeal. Patsy had already spent too much time in her young life feeling like a freak. But the basement had Professor Heckler’s Flea Circus. Patsy was fascinated. “Can I please see the flea circus?” she asked her father. “Please? Please?”

Patrick had seen enough of New York to be wary of basement entertainments, especially in Times Square, and wanted to say no. But this was Patsy’s day in New York, and he wanted to please her, so he said yes. Into the basement they went, Patrick looking behind him as they descended the stairs.

“Really? You’re here to see the fleas?” said the man behind the counter, looking from Patrick to Patsy and back to Patrick again.

The fleas had been individually selected and forced to put on a show. For Patsy, this took some of the glow out of the performance.

He beckoned them down a hallway, deeper into the building. Patrick cast his glance nervously around, looking to see who or what might be there, but the hallway ended in a room where there was, in fact, a flea circus. Patsy was handed a magnifying glass and invited to lean over a countertop to view a toy-sized arena. Real fleas, attached to very thin wires, swung on miniature trapezes. Others raced tiny chariots around a tiny track. Patsy’s father stood with his back to a wall, eyes on the doorway, while Patsy watched two fleas, one in a ballgown, dance a minuet.

“How do they do it?” Patsy wanted to know.

“Oh,” said the man, “They are very educated fleas.”

Even educated fleas, sang Patrick, knowing the Cole Porter tune.

“So they’re trained?” asked Patsy.

“Professor Heckler finds the most talented ones, the most brilliant, advanced fleas, and takes them to his flea school, and trains them himself.”

The fleas had been individually selected and forced to put on a show. For Patsy, this took some of the glow out of the performance. Father and daughter together looked into the tiny arena and considered the flea circus and its highly educated fleas. In the middle of New York, the center of the world, they found fleas harnessed to wires, prepared for daring stunts. Ready to perform. Ready for applause.

High school in Québec ends at Grade 11.

What a great way to document something that Patsy herself perhaps considered not worth writing about. Goes to show that everything is something worth writing about, when done as perfectly as you have.

Very cool piece! It brought back memories of midtown in the early 50s. My Aunt worked at Toffenitis and my uncle at Schraffts (sp?)