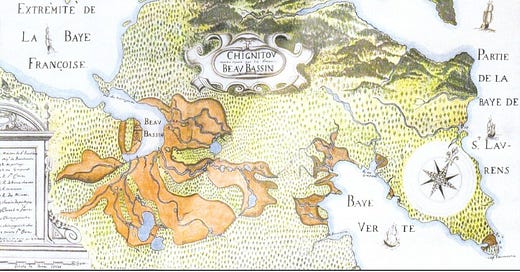

In the winter of 1688, my Morin ancestors were expelled from their village of Beaubassin, Nova Scotia. They walked into the Canadian wilderness taking only what they could carry. The exile of the Morins is an Acadian legend. But to know why they were banished begins with the village of Beaubassin—a story of rebellion, a witch trial, and forbidden love.

The previous installment may be found here:

This installment recounts the surprising outcome of the trial of Jean Campagna

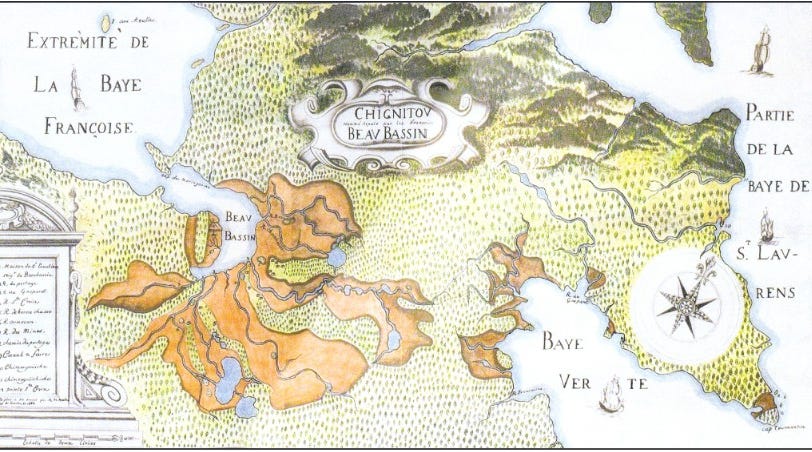

The story so far: In 1671 Jacques Bourgeois, his sons and sons-in-law, establish a new settlement of Beaubassin in the marshlands where Nova Scotia meets New Brunswick. They are soon joined by others seeking independence, including Pierre and Marie Morin. Everyone is engaged in back breaking work of draining the marshes. Then, in 1676, Beaubassin is granted to Michel Le Neuf as his noble fiefdom. To drain the marshes, Le Neuf imposes his feudal right of unpaid labor, the corvée, which the villagers refuse. Le Neuf finds a source of labor in the problematic Jean Campagna. Le Neuf takes the villagers to court to impose the corvée and loses. Le Neuf returns from his failed governorship in Port Royal to a village outraged by Campagna. Le Neuf arrests Jean Campagna for witchcraft.

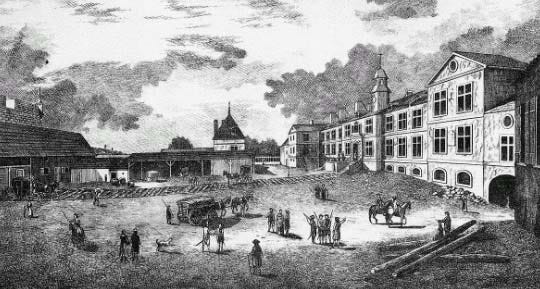

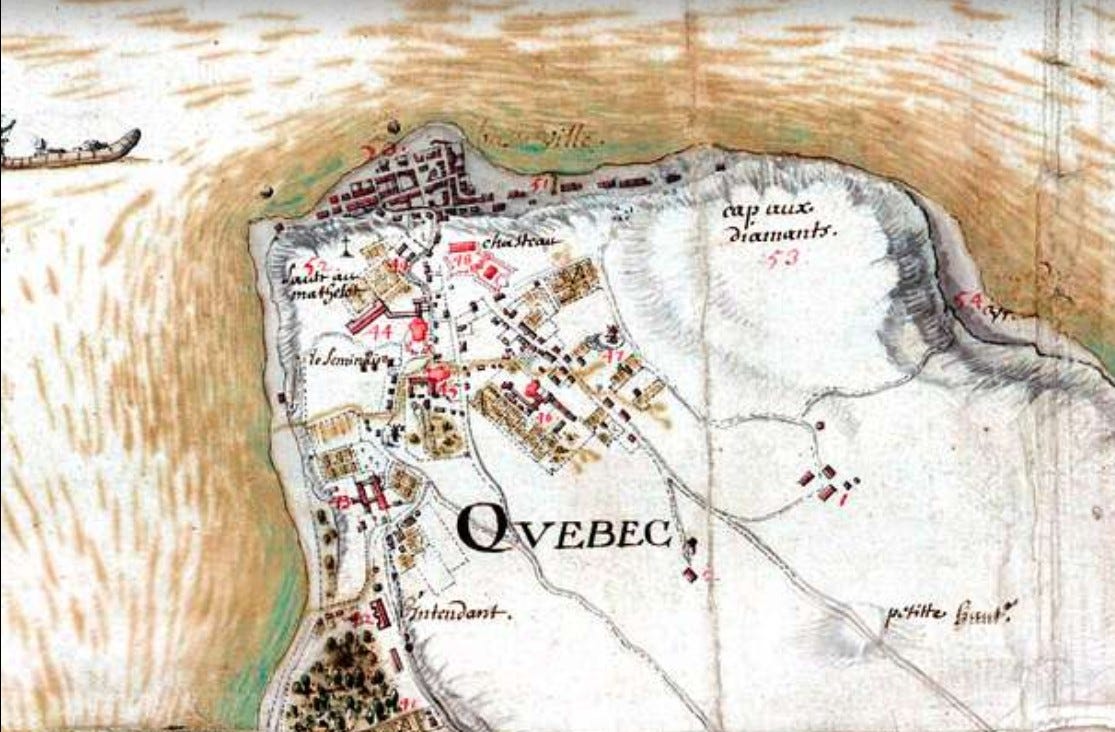

In the spring of 1685, Le Neuf paid his nephew Simon-Pierre Denys 100 livres to take the shackled Jean Campagna on the multiple week journey to Quebec. Upon arrival, Campagna was remanded to the Royal Prison where he awaited the outcome of a judicial investigation by the court of the Provost (Prévoté) the highest royal law court in New France, with the lieutenant général Louis-Théandre Chartier de Lotbinière serving as judge.

A judicial investigation in New France was in place of a conventional trial. The judge reviewed and analyzed the depositions, confrontations, and other evidence collected by Le Neuf. This review was followed by an interrogation of Campagna himself by Chartier on June 25th.

Chartier had Campagna brought before him and asked him if he knew why he was in prison. Campagna said: It was on the orders of Monseigneur Le Neuf. He had his man arrest me and put me in irons, and then he kept me in the bakehouse for nine months.

Chartier asked him about the most serious charges. Campagna denied everything.

The villagers envied his capacity for work— they thought the devil was helping him dig the ditches.

Mercier was angry that the Pellerin girl died and blamed him.

They were jealous of his friendship with Madame Le Neuf, and his gift of butter.

He didn’t breathe into Pellerin’s eye, he didn’t curse anyone’s cows, and he never danced with witches upriver—he liked to get together with some of the villagers outdoors and drink eau de vie.

He had no pact with the devil.

It was all Le Neuf, said Campagna. He told them what to say. He owes me money.1

Standing before the cour de la Prevoté charged with sorcery Jean Campagna had two facts working in his favor.

First, French witchcraft laws were very different from those in other countries, and witch trials unfolded very differently from the better known American cases in Salem Massachusetts. French courts typically rejected testimony of supernatural evidence, such as witness claims of observing shape-shifting or flying through the air. Trial by ordeal, such as throwing a witch in water to see if she or he floats was also not admissible in France. Tangible proof was needed to convict someone of witchcraft. Anything that a rationale person would deem impossible in the natural world, or something that could be neither proved nor disproved, was not credible evidence.2

Second, Chartier, the judge, and the King’s prosecutor, Pierre Duquet de la Chesnaye, were both reputed to be intelligent and rational.

Then, the next day, a new witness appeared before the court.

It is not clear who found Jean-Renaud Bordenave, a man who knew Campagna from Pentageouet, when they were both in the service of Hector de Grandfontaine. If Jean Campagna even knew Bordenave was in Quebec it is doubtful that he could have got word to his old friend from his prison cell, or make a request that he testify. Someone else knew that there was a sympathetic witness out there and managed to find him. But who?

Bordenave would have cut an interesting figure in Chartier’s courtroom. Instead of the usual wool breeches, jerkin, and broad-brimmed hat of a Frenchman, he wore buckskin leggings and moccasins. His face was tattooed. Bordenave had left the fort at Pentageouet, and the life of a Frenchman, some years before and was by then living with native people in a part of the Abenaki Confederacy known as the Dawnland.3

Bordenave remembered Campagna as a good worker who had never made any trouble. Bordenave also said he believed that that Campagna’s accusers owed him money. 4

Two days later, on June 28th, Chartier delivered his verdict. No party would have been pleased with it, other than Le Neuf.

…there appears to be no evidence of the crime of which the said defendant appears to be accused and therefore, we order that the said defendant be released from the royal prisons where he is being held and his sworn commission. It is up to him to seek damages and we claim that he may do so and against whomever he sees fit. On the condition, however, that he may not return to Beaubassin without permission.5

Jean Campagna was thus judged neither guilty nor innocent. He was released from prison due to insufficient proof. He was nevertheless banished from Beaubassin, which suggested that the court was not entirely convinced of his innocence, since banishment would have been the probable sentence had he been convicted. More likely, Chartier thought that the simplest thing to do was to remove the man from the place where he was disturbing public peace.

The villagers would have only learned about the judgment, and that Campagna was free, some weeks later. The people of Beaubassin who believed he was a sorcerer would not feel safe in their beds again knowing that he could be abroad in the night somewhere, casting spells against them or their animals from a distance.

Jean Campagna wouldn’t have been satisfied either. He was free, and the court gave him permission to seek any claims he had against Le Neuf, but there was no way for him to return to Beaubassin to collect the money he was owed.

The only one undoubtedly made happy was Le Neuf.

Jean Campagna walked out of the royal prison in Quebec in June 1685 and was never seen or heard from again. There is no further record of him in Canada or in France. He simply vanished. He may have changed his name, or walked off into the bush as other Frenchmen did. He may have died shortly thereafter from one of the many infectious diseases that claimed even the young and the strong. He simply disappeared from history as mysteriously as a figure erased by a mist off a Chignecto marsh.

Le Neuf, relieved of a sizeable financial liability, enjoyed peace in his domain. It’s not known whether Andrée and Marie remained frightened of the spectre of Campagna once he was gone from the village, or whether they would have preferred he’d been hanged or burned. If the Morin family were disappointed by the judgment, they did not show it. Pierre and Marie Morin grew very close to Le Neuf and his children. In the years that followed, Marie had several more babies to whom Le Neuf was named godfather.

Then a member of the Morin family did something unforgivable.

Next: The Morins accused.

Questioning of Jean Campagna. Gagnon, Jacques, and Jean-Pierre-Yves Pepin, Un sorcier en Acadie: Transcription annotée des minutes d'un procès et document contemporains 1684-1686, Les Éditions historiques et généalogiques Pepin, 2008.

Stephanie Pettigrew has written extensively about Acadians, colonial history, and witch trials in New France. This summary of the legal framework for witch trials in Quebec can be found in a post in the very entertaining and informative Canadian history blog Unwritten Histories.

Pettigrew, Stephanie, “The Halloween Special – Witchcraft in Canada,” Unwritten Histories October 31, 2017. https://www.unwrittenhistories.com/the-halloween-special-witchcraft-in-canada/#more-2915 accessed April 3, 2025.

Court documents indicates that Bordenave was a servant of Jean-Vincent d’Abbadie de Saint-Castin, an ensign of Hector de Grandfontaine who had gone to live in the Abenaki Confederacy. Saint-Castin served as a military advisor to the Abenaki against the English and married the daughter of a sachem of the Penobscot. A later Acadian census record indicates that Bordenave also married a native woman. It’s not known what business brought him to Quebec. There is no description of him in the courtroom— this is my imagining. Gagnon, Jacques, and Jean-Pierre-Yves Pepin, 2008.

Deposition of Jean-Renaud Bordenave. Gagnon, Jacques, and Jean-Pierre-Yves Pepin, 2008.

The documented verdict cited the testimony of 9, and in another place,10, witnesses. 13 witnesses had in fact testified in Beaubassin against Jean Campagna. Gagnon, Jacques, and Jean-Pierre-Yves Pepin, 2008.

Was it an error? It would be tempting to say that certain witness testimony was disregarded, however there other small errors in the prosecutor and judge’s documented statements, so that it may have been just a mistake. Chesnaye in his role as a notary apparently made errors.

André Vachon, DUQUET DE LA CHESNAYE, PIERRE, Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1, Univ. of Toronto,1966 https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/duquet_de_la_chesnaye_pierre Date accessed: June 11, 2025

The French approach to witchcraft on this continent really was different from the English response in the colonies. I have another ancestor -- Barbe Hallay -- who was "demon possessed." The nuns took her in, helped restore her vigor, then put her to work taking care of other patients. https://www.mqup.ca/possession-of-barbe-hallay--the-products-9780228014034.php

And now...waiting to find out what happened to the Morins!

I’m really enjoying the twists and turns of this story. And so interesting about the different approach to accusations of witchcraft.

I love the old map of Quebec. I think I can decipher le seminaire? I taught a class there one semester!