What is Micro-history?

Asking large questions in small places

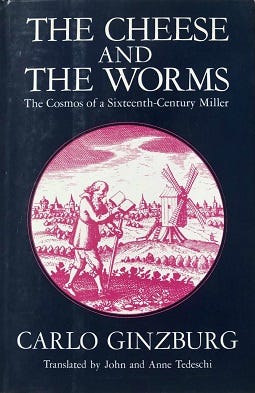

Many years ago, when I was a history graduate student at NYU, I picked up a book entitled The Cheese and the Worms. It told the story of Menocchio, a miller in 16th century Friuli, who was put on trial for heresy. Menocchio spoke freely, challenging church orthodoxy, particularly around the divinity of Christ, the authority of the clergy, and the humanity of non-Christians. Menocchio also had his own unique theory of the universe, which he believed originated from chaos, comparing it to cheese forming with worms inside it. The worms were the angels and God.

The inquisition investigated Menocchio’s books to identify the sources of his heresies. Books were rare things for ordinary men like Menocchio. If you got your hands on a book, you kept it, lived with it, and memorized it before you passed it on. Menocchio did not get a hold of many books in his lifetime, but he read widely—geographies and traveler’s tales, Boccaccio’s Decameron, and lives of the saints—and he engaged fully with all of his readings. He reflected on them and grafted their contents onto his personal experience and existing store of knowledge, much of which was based in folklore and oral culture.

Reconstructing Menocchio’s story from trial transcripts, historian Carlo Ginzburg explored the intersection of oral and written culture in a world of growing literacy. The book upended prevailing notions about the intellectual lives of regular people in this period, and the power of individual thought in a repressive society.

The Cheese and the Worms, published in 1976, was the seminal work of micro-history, focusing deeply on a single, seemingly obscure life to draw broader conclusions about culture, society, and belief in early modern Europe.

Up until then, there had been schools of number-crunching social history studying people at the population level. This kind of research didn’t tell us much about their subjects’ world as they understood it. Micro-history sought to reconstruct the lived experience of regular people in a non-reductive way, to reveal how they interpreted and shaped their world and, in some cases, how they challenged it. Ginzburg’s book inspired other historical studies of ordinary people subverting dominant systems. It should be noted that Ginzburg’s book was not the first work of micro-history, but we still see its influence in research that seeks to illuminate the history of overlooked, marginalized people.

Micro-history is not the same thing as a case study or a one-place study, although these can sometimes be micro-history. It's not genealogy or family history with some "context" attached to it. Instead, micro-history examines one discrete subject to “ask the big questions in small places.”1 The goal is to use the small subject to understand the larger world around it.

When I started writing my family history I wanted to see my ancestors as historical actors with their own agency. History isn’t simply something that happened to our ancestors. I invite everyone to turn the lens around and think about their families as the makers of history. They may have built and sustained their communities. Or perhaps they worked in an industry that changed the landscape of this country. They may have perpetuated and sustained a certain local tradition. Or they may have challenged the prevailing authority structure.

I haven’t engaged in true academic micro-history, but I have borrowed some of its tools and concepts in my research.

Here is an example.

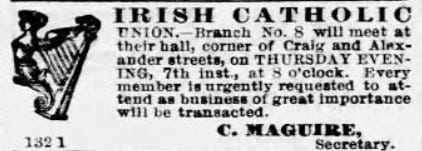

In reading old newspapers, I found out that my great grandfather, Con Maguire, was one of the leaders of a Montreal organization called the Irish Catholic Union, which sprang up in 1877 and disappeared in 1879. I had no idea what this group was or what it was for until I started reading about the politics in the years of its existence.

The Irish Catholic Union emerged at the time of rising Protestant nativism in Montreal. The group disappeared when that movement faded.

Anti-Catholic sentiment followed the flood of Irish Catholic Famine immigrants to North America. By the 1860s and 1870s, the Orange Order, an Irish Protestant fraternal lodge organization with a twin ethos of loyalty to the English king and anti-Catholicism, sprang up in cities everywhere. Its militant youth group, the Young Britons, engaged in recreational street fighting with young Catholics looking to mix it up.

The triumph of the forces of William of Orange over the Jacobite Catholics on July 12th, 1690, marked the start of Protestant absolute rule in Ireland. For centuries after, the Orange Order observed “the Twelfth” with triumphalist parades celebrating Protestant domination in Ireland and elsewhere. In North America, the Orange Order paraded on the Twelfth to provoke and intimidate Catholics, and it made them riot.

In Montreal, the increasing violence brought on by the Orange parade each year culminated in a standoff with the Mayor and an Orange Lodge on July 12th,1878. (You can read the full story here).

As I learned more about the Orange Crisis, I realized that the Irish Catholic Union was a form of street defense for Catholics who felt threatened and also wanted to claim public space for themselves.

My great-grandfather was a newspaper compositor and proof-reader at an Irish Catholic weekly, the True Witness. There is evidence Con may have been radicalized by his boss at the paper, the charismatic Irish nationalist editor Martin Kirwan, who arrived in Montreal the same year that Con and his compatriots formed the Union. In learning about the history of Montreal newspapers in this period, I discovered that fighting in the streets carried over into print, with Protestant nativist dailies maligning Catholics, and Kirwan’s paper attacking the Orange Order in turn.

When the Orange Lodges paraded, Con was out in the streets with the Irish Catholic Union defending his neighborhood from whatever threat he saw out there, real or imagined. But it may not be apparent to anyone reading about the sectarian strife in Montreal in these years just how deeply embedded in the community this pop-up Catholic organization was. Like their more established counterparts, the Orange Lodges, the Irish Catholic Union sponsored neighborhood events, its band held concerts, and its members took part in religious observances and charity drives. It was both street defense and community organization-not unlike the Black Panthers in our own time. They weren’t just a bunch of brawling kids, although some of its members did their fair share of that, too.

When you find these stories you really get a thrill, because you realize that in their own small way your ancestors were not simply witnesses, but makers of history. In researching my family history, I salvaged something small and forgotten that may add to broader urban history, particularly in the way people laid claim to public space. The Orange Crisis was the beginning of the end of a certain kind of urban experience in Montreal. And of course the Orange Crisis itself, brought on by the wave of nativism in the US and Canada in the 1870s, is a mirror for what we are experiencing now.

If you flip the lens and pull it back from your own family story, you may reveal something new about a broader current of history, and sometimes even on our own time.

So how do we write micro-history?

Start with any artifact (a document, an object, a custom, or ritual that hasn’t been of previous historical interest. Ask yourself about the world in which that person or event took place, and see what has been overlooked. We can dig deep to understand it and try to understand the mentalities of the people in that time and place. Start with what it says, as opposed to what you would say to it based on what you already know.

Look for the scattered traces. Different kinds of related artifacts can reconstruct invisible history. These could be court records, contracts, or letters, but they could also be advertisements, objects, and oral history. These small bits across different sources can no only triangulate to see the bigger picture, but they can help us understand their meaning for historical people. These ephemeral traces are essential for marginalized people who did not leave a written record.

Explore the silences. What is missing from the record and why is it missing? This may be the place to find the alternative history of people who have not been written about. In some cases they may have resisted the “official” record or the dominant culture.

Read against the grain. Carlo Ginzburg reconstructed the mind of Menocchio using sources generated by the very people who sent him to the stake. We can use official or institutional records and invert (or subvert!) their intent to recover marginalized experiences. This may be by inference, or filling the gaps with new kinds of artifacts.

Understand the world of the ordinary person as best you can. There is not much left of 19th century Montreal, but I read a lot of old newspapers, seeking to understand what preoccupied people at the time. What interested them, what they worried about, what they thought was funny.

Investigate the everyday. Much of the lives of regular people seemed too commonplace to document. But ordinary experience can often tell us a lot about bigger social, political and economic structures.

As author and Substacker Aimee Liu says, interrogate the weird!2 Original history lives where we don’t understand something. We can often gain insight about the mentality of historical people by decoding and unpacking something strange they said or did. If it’s not clear what the joke is, that is no doubt where you will find some treasure.

Borrowing some of the tools of micro-history to apply to our family story and posing historical questions about our ancestors can result in new and original history.

By writing about our families as micro-history we can:

Reconstruct a missing view of historical lives, highlighting something that has been misunderstood or erased.

Reveal a small event or experience that challenges an existing broad-brush view of history.

Showcase individual agency in a traditional hierarchy or repressive social structure.

When I first got interested in family history as a teenager, I was disappointed that my family weren’t remarkable in any way. But now I am fascinated by their ordinary lives. They have offered me the opportunity to do original historical research, and I have learned so much more about their world than if they had been kings and generals.

The more ordinary your family, the more they may tell us something we didn’t know.

Charles Joyner, "Shared Traditions: Southern History and Folk Culture" (University of Illinois Press, 1999)

Aimee says she learned this gem from the fiction writer and teacher Jim Shepard. (Aimee’s excellent Substack MFA Lore shares insights and writing tips for creative writers, and hosts a collaborative site for MFA alums and faculty covering writing and publishing. Aimee also writes about the history of her own unique family and shares some of her sublime photo paintings.)

Really nice post, Lisa. By the way, my father once told me that the nuns warned all the Catholic kids that if they watched the Protestants marching on the 12th, they'd go blind.

Beautiful. Thank you for sharing on this topic. I love sitting in your classroom. :)