In the winter of 1688 the Morin family were expelled from their village of Beaubassin, Nova Scotia. The exiles included Pierre Morin, his wife Marie, their children, and their children’s families—nineteen people in all—and ranged in age from fifty-four year-old Pierre to his toddler grandchildren. They walked into the Canadian wilderness taking only what they could carry.

The exile of the Morins is an Acadian legend. But no one has told the full story of Beaubassin—a twisted tale of French squatters, a massive earthworks, a scheming feudal lord, a village sex pest, a witch trial, and a forbidden love.

This first part introduces us to the village of Beaubassin.

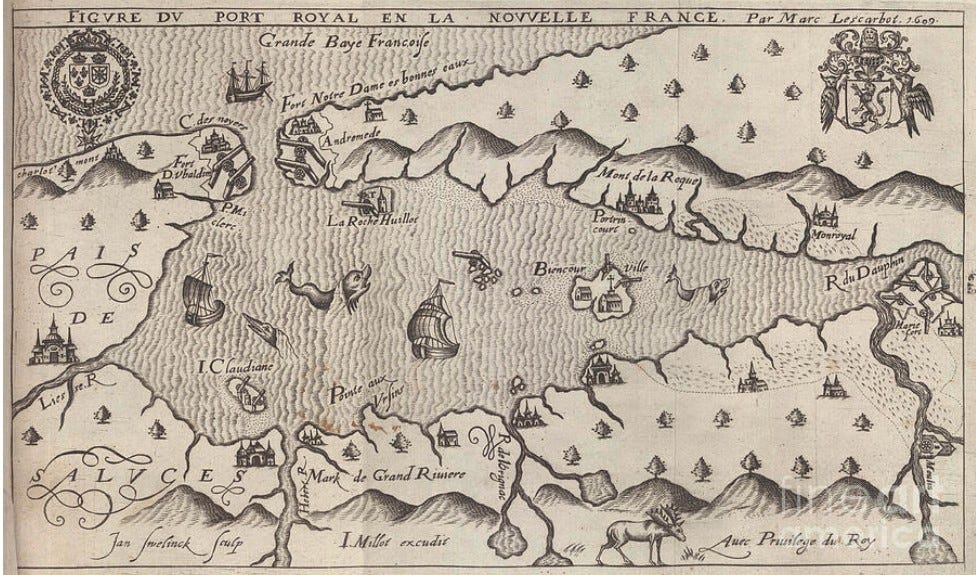

In 1671 Jacques Bourgeois, a doctor and merchant, left his home in Port-Royal, Nova Scotia accompanied by his young ship’s pilot, Pierre Arsenault, three of his sons, and two sons-in-law, Pierre Cyr and Jean Boudrot.

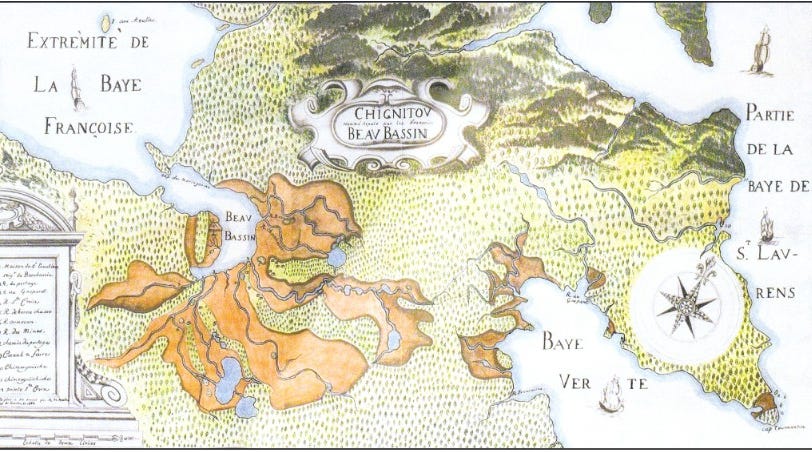

For years Jacques had been making the treacherous journey from Port-Royal to the fog-shrouded upper coast of the bay to meet Mi’kmaw fur traders at a place called Chignecto, or the Great Marsh. This time, however, his sons and sons-in-law planned to stay. They set up camp on the south bank of the Missaguash River, near the present day town of Amherst, on the narrow land passage that connects Nova Scotia to the rest of North America.

Jacques knew this place well. Looking out over the endless expense of mudflats and wind-whipped cordgrass, buzzing with insects and heavy with the scent of salt and decay, Jacques saw possibilities. The mucky earth of the marsh could be drained. In place of the swamp would be pastures thick with yellow salt hay.

His settlement would sit at the western edge of an overland route on the isthmus connecting the Baie Française to the Gulf of St. Lawrence, a portage that was well travelled by Mi’kmaq, who set fish weirs in the marshes each spring. Jacques knew this was the crossroads for anyone travelling between New France to Nova Scotia, inland from the Atlantic, or up the Baie Française to trade goods, most importantly, fur.

The Baie Française was once known by its M’ikmaw name Sigunikt. It’s now called the Bay of Fundy. The tides of Fundy are something out of Exodus. The flow of all the world’s fresh water rivers is less than a single tide, which moves at perilous speed. To the north, the Bay of Fundy gives out into two quieter lesser bays. Jacques established his settlement in a cove tucked inside the smaller of the two.

Acadians usually sought permission from Mi’kmaq to use their land. Given that Jacques had an ongoing business relationship with them, he likely did as well.1 Mi’kmaw families later gathered in Beaubassin, but they were never featured in censuses. Christians among them sought out the Recollect priest for baptisms of their children, which is how we know some called Beaubassin their home.

Jacques’s settlement was a five-day canoe trip or over ten-day walk through the bush from Port Royal—out of range for English raids but still close enough for trade with them when it suited him. Trading with the English was not tolerated by the colonial government, but Beaubassin was far enough away from Port Royal that Bourgeois and his companions could do as they liked.

Fur had made Jacques the richest man in Port Royal. He had been granted his own property, Ile des Cochons, by its Governor some twenty-five years before. Jacques himself did not settle permanently in Beaubassin until the end of his life. Beaubassin was for his children and his legacy.

The other men who went to live in Beaubassin did so for their own private reasons. Already preferring to live an ocean away from France, they probably didn’t care for the scrutiny and petty judgments of small town life. One didn’t have to go much farther from Port-Royal to get to the edge of the map. They preferred this liminal place, where ever-shifting ground turned from swamp to mud, and from mud to water, and where trails vanished into fog.

In exchange for their freedom the settlers eked out their living in a cold, rough land. Winds swept in off the water and blew pitilessly across the marshes, which flooded regularly from the tides of Fundy. Travelers to this place described a landscape of endless grass, mud, and few trees. The small scrubby spruce that could survive the brackish soil were frequently spotted along the route pulled out by their roots by the wind. This landscape matched its inhabitants. The Acadians of Beaubassin would eventually be known for their pure cussedness.

The settlers built low slung homes on dry islands rising out of the wetland. Their cows and sheep grazed on the steep high ridges above the houses. To travel from one home to the other required rowing through the water channels of the marsh, or wading on sunken paths that disappeared with the tide.

Everyone in the settlement took part in back breaking work draining the marshes. This was alongside days filled with growing food, caring for animals, hunting, foraging, and trading fur. Rising out of the swamp were fields of rich marsh grass that would feed fat cattle. They would spend years reshaping the land.

What Mi’kmaw residents thought as they watched the newcomers drain and despoil their marsh has gone unrecorded.

Marshes were drained by way of dykes and aboiteaux, or sluices, which automatically opened at low tide to allow water trapped in the marsh to escape and then closed at high tide to prevent water from getting in. The drainage system converted the salt marshes to pastures. Acadian earthworks, accomplished with only pick, shovel, and plough, over years of toil, remain a feat of engineering and serves as flood protection in the region to this day.

In the years after Jacques and his confrères first arrived at Beaubassin they were joined by others. Among these later arrivals are two families at the center of its story: the Morins and the Kessys.

Pierre Morin

Pierre was born in France in 1634. Apprenticed as a saddler, he emigrated to Port Royal, Nova Scotia in 1661, one of many footloose young Frenchmen seeking his fortune for a few years in the fur trade before returning home with capital to buy land or start a business. Pierre chose to stay.

Pierre married Marie Martin in Port Royal. They homesteaded as tenants on Jacques’s land on Ile des Cochons for a few years before moving with their nine children and livestock to Beaubassin in 1676. The Morins were one of Beaubassin’s prosperous families, with thirty arpents of land, fifteen cows, eight sheep, and twelve pigs. Pierre brought apple seeds from his native Normandy and cultivated apple trees.

Roger Kessy

Another newcomer was an Irishman named Roger Kessy.2 Roger married Marie Poirier, the sister of Michel Poirier, another Port-Royal resident who had settled in Beaubassin a few years after its founding. Roger and his brother-in-law Michel may have been part of the original crew who went to Beaubassin with Jacques, but they were not permanent residents of the village until later.

It’s not clear how an Irishman ended up in Acadia. One story is that Roger was a prisoner or indentured servant of the British who had seized Port-Royal from the French and occupied it for a time before ceding it back to the French in 1670.

In the spring of 1682, Roger and his wife Marie moved to Beaubassin with their four children. Like Pierre, Roger had cattle and cultivated apple trees. Roger’s descendants would one day own vast acreage and giant herds.

Pierre and Marie Morin did not share the bond the other settlers had forged with each other through those hard first years. They were well-known to everyone in Port-Royal, but Pierre was not directly related to Jacques or any of Beaubassin’s other heads of household. The Kessys settled there even later. Roger may have been a fellow Catholic, but he was clearly a foreigner.

Pierre and Marie Morin and Roger and Marie Kessy stood by the community during its first crisis: Soon after Jacques and his followers built their settlement, Beaubassin and the surrounding region was granted to Michel Le Neuf de la Vallière as his noble fiefdom. Beaubassin now had a master.

Le Neuf did not know the challenge that lay ahead. He would soon learn that the people of Beaubassin weren’t good at taking orders.

Next: Michel Le Neuf arrives in Beaubassin with a lot of plans.

Many thanks to Gary Tucker for the use of his sublime photographs of the landscape surrounding the historic site of Beaubassin.

If you wish to see more of his extraordinary work, or order a print, his website may be found here: https://garytuckerphoto.com/

William C. Wicken, “Re-examining Mi’kmaq-Acadian Relations, 1635-1755,” in Sylvie Dépatie et al., “Habitans et Marchands” Twenty Years later: Reading the History of Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Canada (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1998), 93-114. Cited in Anne Marie Lane Jonah, Revealing the History of the Isthmus of Chignecto Toward Truth and Reconciliation.” https://journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/JNBS/article/ view/32890/1882528135 Accessed April 11 2025.

Most likely a French pronunciation of the name “Casey."

Incredibly deep research - impressive. Elegantly written and a pleasure to read.

I always love your writing, Lisa. You've pulled me in so I can hear the strokes of paddles through the water and far-off water birds you'd not even needed to mention. With the orchestra tuned up, I can't wait for the story now.