In the winter of 1688 my Morin ancestors were expelled from their village of Beaubassin, Nova Scotia. They walked into the wilderness taking only what they could carry. The exile of the Morins is an Acadian legend. But to know why they were banished begins with the village of Beaubassin—a story of rebellion, a witch trial, and forbidden love.

The latest installment may be found here:

In this installment, the simmering conflict between Le Neuf and the villagers boils over.

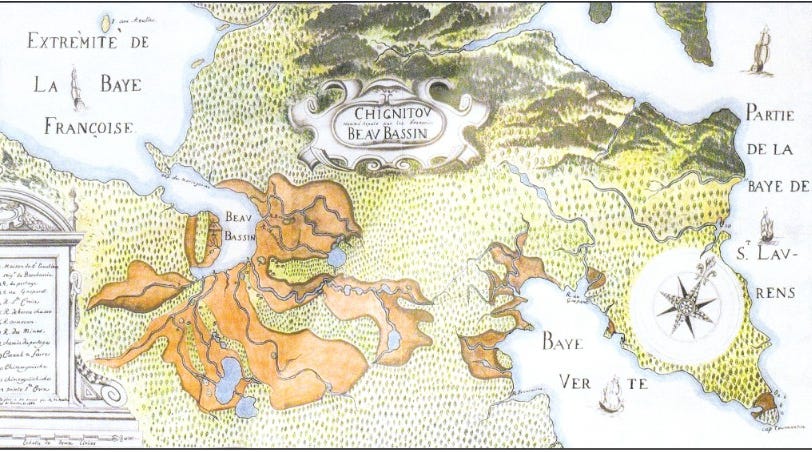

The story so far: In 1671 Jacques Bourgeois, his sons and sons-in-law, establish a new settlement of Beaubassin, in the marshlands where Nova Scotia meets New Brunswick. They are soon joined by others seeking independence, including Pierre and Marie Morin. Everyone is engaged in back breaking work of draining the marshes. Then, in 1676, Beaubassin is granted to Michel Le Neuf as his noble fiefdom. Le Neuf imposes his feudal right to the corvée, enforced labor on his behalf, which the villagers reject. Le Neuf and the villagers find a source of labor in the problematic Jean Campagna. A deadly epidemic sweeps through the settlement. Le Neuf, fed up with resistance to the corvée, declares existing contracts in his domain null and void.

Le Neuf thought: these yokels will never submit. There had to be a reason why they were so confident that they did not have to.

It became apparent to Le Neuf there was only one explanation for this continued defiance. There was something he had worked hard to conceal since he arrived in Beaubassin, and these illiterate villagers somehow found out about it. But how?

There was only one possible source for this kind of information: The progenitor of those flagrant flouters of his authority in his domain, the founder of Beaubassin himself, Jacques Bourgeois.

Le Neuf knew Bourgeois cast a cold eye on his seigneurie. Beaubassin had more or less belonged to Bourgeois before it was granted to Le Neuf, and he monitored everything that went on in the village from his home at Port-Royal.

For Le Neuf this was a personal legal matter, but people talk. Someone from New France, no doubt someone who didn’t like him—and there were many of them—must have told Jacques Bourgeois that he, Le Neuf, did not yet have full title to the seigneurie. Le Neuf had not yet received the formal decree from the Crown. Moreover, the original settlers had the right to be there.

Bourgeois probably told his sons to wait. Let this parvenu wear himself out arguing. You owe him nothing. And his sons told the others.1

Or else it was the women. Madame Le Neuf told him the village women did nothing but gossip. 2They all seemed to be related to Bourgeois and each other by marriage. The jabbering women found out and then hen-pecked their men. How else would these ditch diggers have the will to go on defying him?

Le Neuf knew time was running out. He’d been in Beaubassin for four years and had little to show for it. He’d made so many reckless promises about a place he’d never seen. He needed more land under the plough. Then there was new competition from a neighboring concession granted to a commercial venture, the Compagnie d’Acadie.

The time had come for extreme measures.

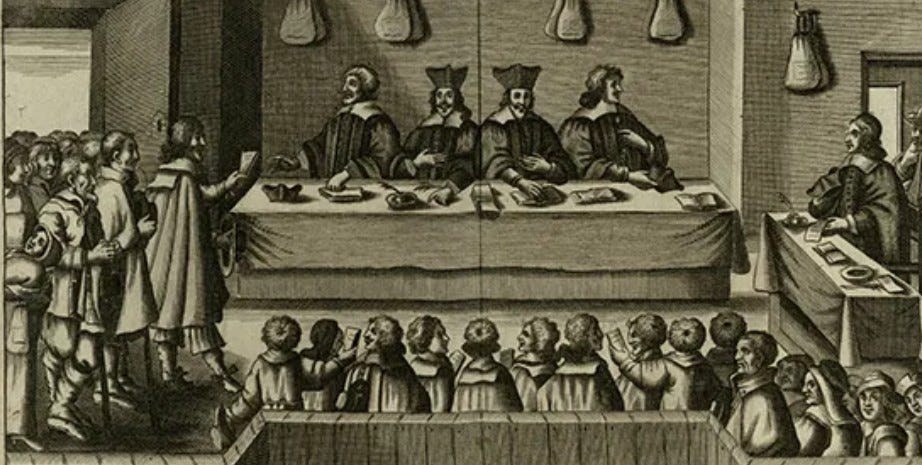

In March 1682 Le Neuf filed a complaint with the Sovereign Council in Quebec. He had the Council serve summonses to eleven men of Beaubassin for refusing Le Neuf’s new tenant contracts.

The eleven men named in the suit were heads of families in the village, except for Pierre Arsenault, Jacques Bourgeois’s ship pilot who was not living in Beaubassin by then. But Arsenault had land in the village, so he owed Le Neuf, too. And Le Neuf was determined to stamp out resistance from everyone in the original Bourgeois crew.3

Then there were two other men named in the lawsuit who annoyed and intrigued Le Neuf: Kessy and Morin.

Like the others they were married to troublemakers. It was true that Kessy was married to the sister of one of the defiant ones, but even these Acadian rubes knew enough not to trust an Irishman.4 Morin had no ties to anyone in the village, except for his wife’s sister, Pellerin’s widow.

He noted that Morin and Kessy were comrades of a kind. Maybe because they could talk to each other about their apple trees and not bore the rest of the village with their endless tattle about whip and tongue grafting and rootstocks and scions and who was right about breeding the wild native crabs.5 But it may also have been because they were both outsiders.

These two may have taken the side of the résistants for any number of reasons, but in Le Neuf’s mind they did it mainly because they could. Such unprincipled people were the ones to peel off from the rest when the right time came. Le Neuf would remember this.

Le Neuf went to Quebec with his suit. As the protégé of Governor General Frontenac, he thought the odds were in his favor.

The Council gave its verdict. The corvée would never be part of the terms of Le Neuf’s concession.6 The Council upheld the rule Le Neuf had tried to bend: The settlers of Beaubassin owed him nothing.7

The defeated Le Neuf got a consolation prize. No sooner did he lose in court than the rulers of New France appointed him Governor of Acadia.

Le Neuf did not sulk in Beaubassin for long. He installed himself in Port-Royal. He decided that his family would stay behind in the settlement. He appointed Madame Le Neuf the responsable for collecting the rent. Money was becoming a problem. Without the corvée he’d been paying for labor, and he owed everybody.

Now that he was Governor, Le Neuf set about enriching himself first. Given Beaubassin’s reliance on English goods, Le Neuf had already cultivated connections with the Massachusetts Bay Colony and its Governor, Simon Bradstreet. As Governor of Acadia, Le Neuf decided to grant the English fishing licenses. Unfortunately, the licenses were in the waters of other concession-holders, notably Alexandre Le Borgne de Belle-Isle, the seigneur of Port-Royal himself, and Bergier of the Compagnie d’Acadie. They wasted no time in lodging their grievances.

Le Neuf was getting talked about. The intendant Jacques de Meulles gave him friendly advice to tread carefully, especially with the Compagnie.8 Bergier was, after all, the King’s lieutenant. Le Neuf scoffed at this. He knew Meulles himself was busy selling fur trading licenses to any buffoon who crossed his path. He was a fine one to tell him what to do.9

Meanwhile, Madame Le Neuf wrote to her husband from Beaubassin.10 The harvest was poor, and the villagers had little wheat to hand over. She had been collecting a lot of promissory notes.

She reported that the Pellerin widow, still mad with grief, was telling anyone who would listen that someone had killed her husband and child and she knew who. Did no one remember how Campagna had threatened her? The only question in her mind was how he managed to infect them. Madame Le Neuf noted that it was true that everyone Campagna quarreled with was either dead or walking around with pockmarked faces.

Le Neuf wrote back that Campagna quarreled with everyone and she should stop repeating tittle-tattle. He had always thought her more sensible than that.

Madame Le Neuf wrote again and reported that Campagna had come to Ile de la Vallière uninvited. He did not bring any wheat. Instead he demanded to be paid for the last three seasons of work he had done for Monsieur. Did Monsieur not pay him? 11

Le Neuf immediately sent back an angry note telling his wife to ignore Campagna and to instruct their man Haché not to let him near the house.

In her next letter Madame Le Neuf said that Campagna had showed up again to Ile de la Vallière and asked to speak to her alone in the garden, which was of course entirely improper. Haché and their sons were out fishing and she was by herself with the girls and the servants. She went to the garden to tell Campagna to go away and he was quite impudent. He said he want to ‘bring her some butter.’12 What slang was this?

Le Neuf read the letter and kicked over a chair. He wants another beating from me. I will deal with this fool when I am back in Beaubassin.

Meanwhile, loud complaints about Le Neuf were getting back to Quebec. By giving the English fishing licenses, Le Neuf was allowing their ships into the Bay. The inhabitants of Port Royal long lived in fear of New Englander raids and kept their cannons trained on what is now the Annapolis River, pointed in the direction from which the English had attacked years before. They remembered the looting and burning. What on earth was he thinking?

Then Le Neuf received another letter—this one from Quebec informing him that he was dismissed and was to vacate the Governorship immediately. From somewhere out on Ile des Cochons, Jacques Bourgeois was chuckling.

Le Neuf was preparing his departure on the Saint-Antoine for its next sail from Port Royal when suddenly his ship was spotted in the port. Before he could send word to find out why, his pilot Cochu and his son Alexandre were standing in the doorway saying that he must come to Beaubassin right away. Madame was not well. 13

When Le Neuf arrived home, his wife was dead and the whole village was churning with rage.

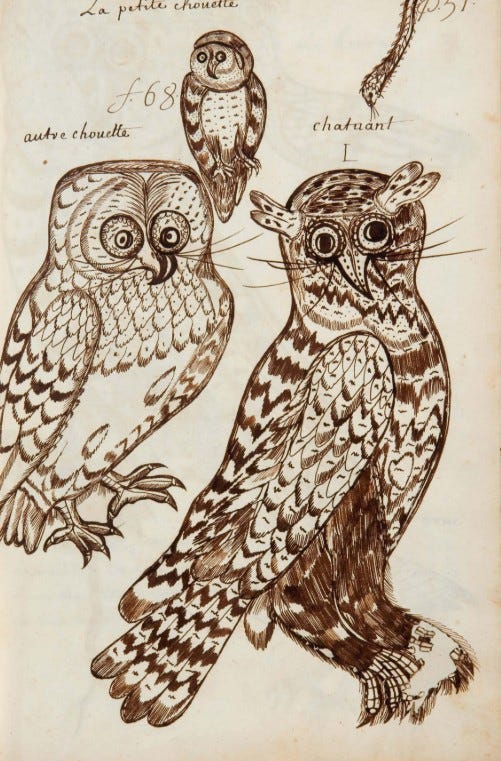

Next: Curses and spells

Not certain who would have known this, but New France was a small place and confirmation from the Crown would have been a matter of public record. This information may well have travelled by word of mouth to people who did not read.

The depositions from the trial refer to his wife as “mademoiselle” or “la demoiselle" which sounds odd to our modern ears to describe a 40 year old married woman. To eliminate any confusion I used the modern “madame.”

The eleven:

Germain Bourgeois (son of Jacques Bourgeois)

Guillaume Bourgeois (son of Jacques Bourgeois)

Claude Dugas (son-in-law of Jacques Bourgeois)

Jean-Aubin Mignault (brother-in-law of Claude Dugas)

Germain Girouard (son-in-law of Jacques Bourgeois)

Jacques Belou (brother-in-law of Germain Girouard)

Thomas Cormier (brother-in-law of Germain Girouard)

Guyon Chiasson

Michel Poirier (son-in-law of Guyon Chiasson)

Roger Kessy (son-in-law of Michel Poirier)

Pierre Morin

The deposition makes a point of telling the reader that Kessy is Irish.

My imagining, but we know that they were the two villagers who grew apple trees.

There is no record of the actual verdict from the Council. We know that the terms of the written concession does not include right to the corvée. We also know that the men of Beaubassin stayed in the village. It is possible that the men of Beaubassin and Le Neuf agreed to a contract that was mutually acceptable— if it included unpaid work for Le Neuf, it would have been something that the villagers could live with, or received some other benefit from.

Twenty-two years later Le Neuf would travel to France himself to petition the French royal court for his seigneurie to finally be ratified. To do it, this Canadian-born son of a fur-trapper had to navigate Versailles. He had the right buckles on his shoes and had learned how deeply to bow, and when, and to whom, since he got his decree. It was a bittersweet victory. The official decree confirmed La Vallière’s seigneurial claims to Beaubassin, but it also recognized the rights of its original settlers.

Jacques de Meulles was the new intendant of New France in 1682. He was eventually dismissed due to graft.

W. J. Eccles, MEULLES, JACQUES DE, Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 2, University of Toronto/ Université de Laval, 1969-1982. .https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/meulles_jacques_de_2E.html#citations Date accessed May 10, 2025.

There are no such surviving letters. While Madame Le Neuf would have undoubtedly communicated with her husband while he was in Port-Royal, these letters are my invention to fill the reader in on what was transpiring in Beaubassin in Le Neuf’s absence.

Depositions at the trial confirmed that by 1684 Le Neuf owed Campagna about 700 livres, an astonishing sum and probably representing several years’ work.

From the deposition of Marie Gaudet and Francois Toupin, 1684. Gagnon, Jacques, and Jean-Pierre-Yves Pepin, Un sorcier en Acadie: Transcription annotée des minutes d'un procès et document contemporains 1684-1686, Les Éditions historiques et généalogiques Pepin, 2008.

We don’t know the exact date of the death of Madame Le Neuf, but it would have most likely been during Le Neuf’s absence from Beaubassin and not during the epidemic of 1678-79) and certainly before the Campagna legal case as she is noted as passed away in the depositions.

So much for the peaceful pastoral life, heh?

This is great! Curious. How do you know what he felt about the women — and their gossip? Was that written somewhere?