In the winter of 1688, my Morin ancestors were expelled from their village of Beaubassin, Nova Scotia. They walked into the wilderness taking only what they could carry. The exile of the Morins is an Acadian legend. But to know why they were banished begins with the village of Beaubassin—a story of rebellion, a witch trial, and forbidden love.

The previous installment may be found here:

In this installment, complaints about Jean Campagna get louder and Le Neuf makes some friends

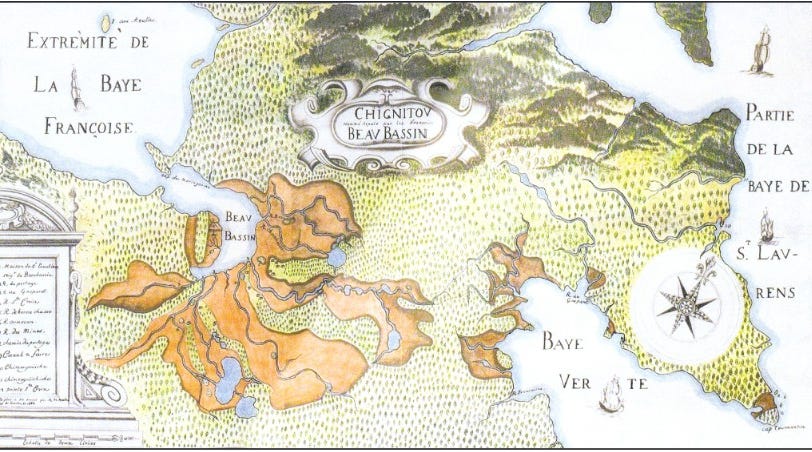

The story so far: In 1671 Jacques Bourgeois, his sons, and sons-in-law, establish the settlement of Beaubassin in the marshlands where Nova Scotia meets New Brunswick. They are joined by others seeking independence, including Pierre and Marie Morin. Everyone is engaged in back breaking work of draining the marshes. In 1676 Beaubassin is granted to Michel Le Neuf as his noble fiefdom. Le Neuf tries unsuccessfully to impose his feudal right to labor (corvée). Le Neuf and the villagers find a source of labor in the problematic Jean Campagna. A deadly epidemic sweeps through the settlement. Le Neuf takes the men of Beaubassin to court in Quebec for refusing the corvée. Le Neuf is appointed and soon dismissed as Governor of Acadia. He returns to a village in turmoil.

The spring of 1684 was late.1 This was unnerving in a place where the growing season was so short every day counted. Starting from the time the first dyke was built, three years had to pass to see something resembling a meadow. More for a decent harvest of that hard red winter wheat which baked into the dense chewy boules that staved exhaustion.

There had been several poor harvests. Buying food from the English was no longer an option. And now there was something wrong with the cattle.

The villagers had turned their cows out to pasture as soon as the grass came in, but the animals were bloated, listless, and off their feed, and the heifers were not producing as much milk. The people of Beaubassin were worried.

In April, Michel Le Neuf was dismissed from the Governor’s chair. By the time he returned to Beaubassin, Madame Le Neuf was dead.2 She had left seven motherless children ranging in age from eighteen-year-old Alexandre to three-year-old Barbe.

Le Neuf arrived home still enraged over the visit to his wife by the insolent Campagna, who had come to Ile de la Vallière uninvited, and not even bringing the cens or the champart,3 but instead offering a gift of butter. Campagna had no cows. He must have stolen the butter or won it in a bet.

Campagna no doubt had an axe to grind ever since he got a thrashing from Le Neuf over the Godin business. It would be hard to conceal the taste of any poisonous marsh flowers in butter, and rancid butter did not kill anyone, so Le Neuf reasoned that Campagna did not try to poison his wife. But the idea of this greasy ploughman trying to seduce her while he, Le Neuf, was away, and thinking she would succumb to an offer of butter like some barefoot wench was enraging. He was asking for more than a beating the next time he crossed Le Neuf’s path.

He spent the next few days with his account books. Madame Le Neuf had left them in a terrible state, even though Le Neuf’s father, Jacques, had at one point come to Beaubassin to help her collect what was due.4 The books revealed that Le Neuf was on a financial precipice.

Trade from the Saint-Antoine was falling off. He was also now cut off from doing business with the Bostonians. He’d used most of his ready cash in prior years to pay for the building of the church and the mill.

On top of it all, the men working on the marsh, the ones he’d had to pay, were demanding money he owed them. And who was the man who had built mile upon mile of cribwork of wood and soil and was now demanding 770 livres in back pay? None other than that pest, Campagna.

His rage doubled when he saw in the account books that Campagna had not paid him any feudal dues, but had instead distributed his crop to some of the hungrier villagers as some kind of protest.5 He was a little late to the resistance, thought Le Neuf. Perhaps Campagna was starting to understand how much the others didn’t like him.

Before he could deal with Campagna, he had to attend to the crowd outside his door asking him to adjudicate their small matters. The Bourgeois crew never came to Ile de la Vallière, preferring to settle disputes between themselves. Today, he saw an unexpected face among the petitioners. It was Andrée Mercier, Pellerin’s widow.

Jean Campagna is a murderer.

Murder is beyond my local authority. He would have to be tried in Quebec, said Le Neuf.

Then arrest him.

What evidence do you have?

My husband and child are dead. He must have poisoned them.

What proof do you have that he poisoned them?

Maybe it wasn’t poison. He cursed them. Or cast a spell. He threatened me.

These are notions, Madame, not proof, said Le Neuf. Do you have proof?

What about the Kessys?6

The story tumbled out. Just a few weeks ago, Campagna turned up at the Kessy home drunk on eau de vie and asked Roger Kessy if he could marry his daughter Marie.

Kessy had witnessed the man’s temper, especially when he was drunk, especially when he was rebuffed. Kessy was alone on his property with the brute. So he told Campagna to ask Madame Kessy, who wasn’t home. Campagna sat with his bottle and awaited her return.

When Madame Kessy came home she immediately refused Campagna on behalf of Marie. Her daughter wasn’t marrying some Poitevin ditch digger. Campagna started yelling and told both Kessys they would be sorry. Madame Kessy threw him out of the house and said he was a fool and she was not afraid of him.7

Le Neuf told Andrée he would look into the matter.

He knew from his censitaire rolls that the Kessys had a very small piece of land. Their only wealth in this world were their cows. Seven of them were sick: three pregnant heifers, a young heifer, and two young oxen.

Later that day Le Neuf set out alone. He rowed to the north side of the Marguerite river and climbed a path lined with midget apple trees until he reached the top of the small hill called La Butte à Roger.

Roger Kessy had a good view of traffic on the river from his front door, and so was apprehensive and waiting for Le Neuf by the time he reached the house.

I hear your beasts are poorly, said Le Neuf.

My cattles are better, said Kessy. Despite his years in Acadia, Kessy’s French was still imperfect. The spring grass come in too sweet and they ate too much of it. I took them up the hill and I gave them the old second cut hay, and they got better.

Kessy paused. Le Neuf recognized the meek look of someone about to petition him for something. Monseigneur, something must be done about Campagna. He made so much trouble for the Pellerins. Now he makes trouble for us. My wife says—

Le Neuf cut him off. We both know why the cows got sick. They will remain sick for now. You will not mention the composition of the spring grass to anyone, but tell your neighbors that those pastures may have been cursed. Father Moreau will bless the cows. Then they will get better.

As Kessy digested this he wore the same bland face all the villagers had when they wished to conceal from Le Neuf what they were thinking. Then he said: Some think that Andrée Mercier is out of her head. But you can tell everyone that Roger Kessy believes her.

Le Neuf rowed back to Ile de la Vallière with his treasure.8

Le Neuf waited until Sunday, when everyone was arriving at the Recollect church for Mass. In front of the assembled villagers Le Neuf kicked Campagna and beat him with the side of his sword, shouting that he would run him through with it if he did not leave people's animals alone.9

After that, all Le Neuf did nothing. Except let people talk.

Father Moreau blessed the Kessy cows. The next day, Kessy reported to his neighbors that he went into his barn and all his animals were standing.10

Andrée told everyone that this was proof that Campagna had cursed the cows. People started sharing more stories about Campagna.

Jean-Aubin Mignault said: Remember when Campagna said my fields wouldn’t yield anything? It must have been a curse.

And what about Madame Le Neuf? How did she die?

After Mass one Sunday later in the summer, as Le Neuf received the same polite, impenetrable greetings from the Bourgeois families, he asked the Morins, the Merciers, the Kessys, the Mignaults, and the Godins to wait behind. As the local representative of the King’s justice, he wanted to speak to them about some recent events.

Not long after, Le Neuf ordered his man Haché to arrest Jean Campagna.

1683-1684 was an especially severe winter in Europe. Nova Scotia would have also experienced unusual cold, given the widespread climatic anomalies associated with the Little Ice Age.

We don’t know the exact date of the death of Madame Le Neuf, but it most likely occurred during Le Neuf’s absence from Beaubassin and certainly before the Campagna legal case, as she is referred to as deceased in the documents.

Feudal dues owed the lord. Cens was cash and champart was a portion of the harvest.

From the interrogation and testimony of Jean Campagna, 1685. Gagnon, Jacques, and Jean-Pierre-Yves Pepin, Un sorcier en Acadie: Transcription annotée des minutes d'un procès et document contemporains 1684-1686, Les Éditions historiques et généalogiques Pepin, 2008.

From the interrogation and testimony of Jean Campagna, 1685. Gagnon, Jacques, and Jean-Pierre-Yves Pepin, 2008.

This conversation is my imagining, based on what follows.

Depositions of Roger and Marie Kessy. Gagnon, Jacques, and Jean-Pierre-Yves Pepin, 2008.

This conversation is my imagining, based on what follows.

According to deposition of Pierre Godin, Le Neuf beat Campagna and threatened him but that this event took place at Campagna’s home upriver from Beaubassin.

Deposition of Pierre Godin, Gagnon, Jacques, and Jean-Pierre-Yves Pepin, 2008.

So, the previous post left me wondering what had happened to Madame Le Neuf and suspecting Jean Campagna (who by all accounts was a horrible man) ... But this new post has me feeling a little sorry for Jean Campagna ... Twists and turns ... Looking forward to see where this goes next time ...

Bonjour Lisa, je viens d'attraper cette histoire au colet pour la première fois. Votre écriture est très dynamique, claire et entrainante. Il est fascinant d'imaginer le sort des premières famille en Nouvelle-France au 17e siècle. Et je suis particulièrement curieuse d'en apprendre plus à propos de Beaubassin, ses gens et son histoire méconnue.