Beaubassin 1687: Part 9 - As Sheep Without a Shepherd

Amid all the official accounting, something was going unnoticed...

In the winter of 1688, my Morin ancestors were expelled from their village of Beaubassin, Nova Scotia. They walked into the Canadian wilderness taking only what they could carry. The exile of the Morins is an Acadian legend. But to know why they were banished begins with the village of Beaubassin—a story of rebellion, a witch trial, and forbidden love.

The previous installment may be found here:

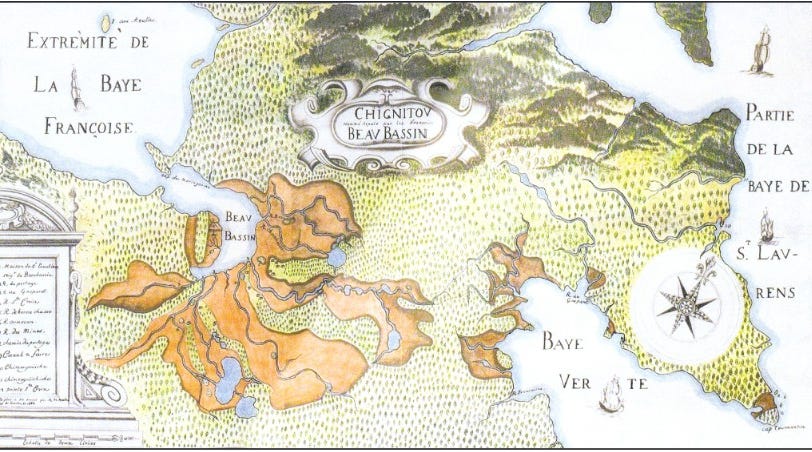

The story so far: In 1671 Jacques Bourgeois, his sons and sons-in-law, establish a new settlement of Beaubassin in the marshlands where Nova Scotia meets New Brunswick. They are soon joined by others seeking independence, including Pierre and Marie Morin. Everyone is engaged in back breaking work of draining the marshes. Then, in 1676, Beaubassin is granted to Michel Le Neuf as his noble fiefdom. To drain the marshes, Le Neuf imposes his feudal right of unpaid labor, the corvée, which the villagers refuse. Le Neuf finds a source of labor in the problematic Jean Campagna. Le Neuf takes the villagers to court to impose the corvée and loses. Le Neuf returns from his failed governorship in Port Royal to a village outraged by Campagna. Le Neuf arrests Jean Campagna for witchcraft. In Quebec the high court rules that there is not enough proof to convict Campagna, who goes free. Le Neuf returns to the village free of Campagna the pest. The Morin family grows close to Le Neuf.

The dust settled on l’affaire Campagna.

Le Neuf never paid the 770 livres he owed Jean Campagna for what amounted to years of digging ditches and building dykes,1 but with over 400 arpents of arable land now in the settlement, Le Neuf and the villagers began to enjoy the fruits of Campagna’s years of toil.

Pierre and Marie Morin’s family grew. Two more boys were born, bringing their family to ten. Their eldest son, Pierre fils, married Françoise, the eldest daughter of Guyon Chiasson. The Morins’ eldest daughter Marie married Le Neuf’s pilot Jacques Cochu.

The remaining Morin children included the as-yet-unmarried Louis, now in his twenties. Antoine and Anne Morin were teenagers. Anne would soon be ready to marry. The other Morin offspring, Jacques, Charles, Jean-Marie, Simon-Joseph, and Jacques, were still children. Jacques and Simon-Joseph were both the godchildren of Michel Le Neuf’s eldest daughter Marie-Josephe.2

In the autumn following the Campagna trial, Le Neuf was paid the honor of an official visit from his old ally, the intendant Jean de Meulles, whom he hosted at Beaubassin and ferried to and from Port-Royal on the Saint-Antoine. Meulles wrote many flattering things about Le Neuf’s domain but reported that there still wasn’t enough land under cultivation, and that the cattle were poor.

Shortly thereafter Beaubassin’s priest Father Moreau left the settlement to become the superior of his order in Quebec. As a Recollet missionary, Father Moreau had never sought to be more than a simple messenger of the Gospel. He had not taken part in the arrest and trial of Jean Campagna. The church he had requested from Le Neuf was a mud hut.3 In his years in Beaubassin Father Moreau had baptized, married, and buried Acadians and Mi’k maq alike. The people of Chignecto were left without a priest for almost two years.

The Bishop of Quebec, Jean-Baptiste de Saint-Vallier also passed through Beaubassin in the wake of Father Moreau’s departure. Saint-Vallier was not impressed by the village church, which he thought was flimsy and would not long survive the elements. The Bishop wrote that Beaubassin was badly in need of a priest. The villagers were spending too much time drinking eau de vie with the savages. 4

Son Excellence had the exact man in mind.

Twenty years earlier, a Sulpician named Claude Trouvé had founded the Quinte mission on the shores of Lake Ontario. He was called back to France by his father, who was sick and in debt. Trouvé was living in Touraine and serving as a parish priest when the new Bishop of Quebec was scouting clerics to join him in New France. Saint-Vallier insisted Trouvé to return to Canada and arranged to pay off his family’s debts. Trouvé arrived back in New France, now a protégé of the Bishop of Quebec and required to do his bidding. His first mission on behalf of the Bishop was to Beaubassin.

The ambitious Sulpician and the crafty Le Neuf would prove to be a poisonous mix.

After two rounds of official visits, Le Neuf was told to provide a status report on Acadia to the colonial authorities in France. He sailed for La Rochelle, leaving his domain in the hands of Claude-Sébastien de Villieu, a new arrival to Canada. Villieu was a veteran some of the bloodiest sieges of France’s war with the Spanish Netherlands and no doubt relished the peace of Chignecto. He wasted no time in setting up his own fur concession with the Mi’k maq, but he was fair in his dealings with the people of Beaubassin, who found him an improvement over Le Neuf.5

While in France Le Neuf also took delivery of something he had arranged. In June 1687, in La Rochelle, he married his deceased wife’s cousin, a widow named Françoise Denys, daughter of Simon Denys de La Trinité, the younger brother of Le Neuf’s previous father-in-law Nicolas Denys.

Le Neuf allied himself a second time with the powerful Denys family. He could now set his sights on other strategic mergers he could arrange through his daughters.

Le Neuf had once again left his family behind in Beaubassin. The children ranged in age from twenty-year-old Alexandre to four-year-old Barbe. Just behind Alexandre in age were Jacques, who was 16, and Marie-Josephe, just 15.

Their father was on an overseas voyage, their mother was dead, and they had been left in the charge of an underage brother and a complete stranger—a battle-worn soldier occupied by getting rich in the fur trade. The young Le Neufs were on their own.6

There were just enough young, unmarried teenaged boys and girls in Beaubassin for them to have a social world all their own. With the exception of the three Cormier children, Marie Blou, and Jean Cyr, the other young people were all offspring of the Morins and the Merciers.7

Le Neuf’s children would therefore be primarily consorting with the progeny of the village families allied and indebted to him. They would be in safe hands.8 Marie-Josephe Le Neuf had known the elder Morin children, Louis, Antoine, and Anne, since she was a small child, and the two families had grown closer during the Campagna trial.

Beaubassin may have been under official scrutiny, but in 1687 no one was watching Louis Morin and Marie-Josephe Le Neuf. They fell in love.

In the new year of 1688, the abbé Trouvé arrived in Beaubassin as the new village priest. Le Neuf returned home with his new wife. Upon seeing her father, Marie-Josephe could not conceal the truth from him: She was pregnant.

Next: Le Neuf’s revenge

Gagnon, Jacques, and Jean-Pierre-Yves Pepin, Un sorcier en Acadie: Transcription annotée des minutes d'un procès et document contemporains 1684-1686, Les Éditions historiques et généalogiques Pepin, 2008, p.41.

My story owes much to Myriam Marsaud’s in-depth study of Beaubassin social alliances as seen in the choices of marriage witnesses and baptismal sponsors. The motivations for the choices were complex and to some degree inconclusive beyond a few salient patterns that reveal two “poles” of social connection: one focused on the Bourgeois family and allies, and the other the nexus of Morins-Merciers-Kessys-Le Neufs. These alliances were not consistently expressed through marriage and baptismal records, and there were no doubt other considerations behind the choices. The choices may reveal even shifting alliances or periods of détente during the war over the corvée. (Marie Morin was named godmother to Barbe Le Neuf in 1682, when her husband was named in Le Neuf’s suit and Le Neuf was a witness to Marie Morin’s marriage to Jacques Cochu.)

Marsaud’s research does suggest that the Morins and Andrée Pellerin Mercier may have already been allied with Le Neuf long before the Campagna witch trial (Andrée similarly having named Le Neuf’s manservant Haché as the godfather of her first baby with Mercier in 1682, and naming the second in 1683 after Le Neuf’s eldest boy who was godfather.)

My account simplifies, and no doubt muddies, the complex and hidden web of relationships in this village for the sake of the story. Marsaud, Myriam, “L’étranger qui dérange : le procès de sorcellerie de Jean Campagnard: miroir d'une communauté acadienne, Beaubassin, 1685,” Thèse de maîtrise, Université de Moncton, 1993.

A more recent study on Beaubassin delves further into the social complexities of the settlement and draws further connections to the villagers and Le Neuf to the local Mi’k maq people. Gregory Kennedy, Thomas Peace, and Stephanie Pettigrew, Social Networks across Chignecto: Applying Social Network Analysis to Acadie, Mi’kma’ki, and Nova Scotia, 1670-1751 Acadiensis Vol. 47, No. 1 (WINTER/SPRING-HIVER/PRINTEMPS 2018), pp. 8-40.

Baudry, René, MOIREAU (Moreau), CLAUDE, Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 2, University of Toronto/Université Laval,1969, revised 1982. https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/moireau_claude_2E.html accessed June 19, 2025.

de La Croix de Chevrières de Saint-Vallier, Jean-Baptiste, “Etat Présent de l’Eglise et de la Colonie Française dans la Nouvelle-France” in Gagnon, Jacques, and Jean-Pierre-Yves Pepin, Un sorcier en Acadie: Transcription annotée des minutes d'un procès et document contemporains 1684-1686, Les Éditions historiques et généalogiques Pepin, 2008.

In letters dated 29 September 1700 and 25 November 1703, Villieu’s son Claude-Sébastien states that Villieu had been in the services since 1674 and that he had fought in Flanders, Germany, Catalonia, and Roussillon for 15 years prior to coming to Canada. The Flanders campaign had included some of the worst battles and sieges under the command of Vauban. At least one contemporary witness indicated that Villieu was well liked by Acadian settlers. Taillemite, Étienne, “VILLIEU, CLAUDE-SÉBASTIEN DE,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 2, Univ of Toronto/Université Laval, 1969 (revised 1982). https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/villieu_claude_sebastien_de_2E.html Accessed June 19, 2025.

My speculation. Worth noting that Le Neuf’s household did include adult servants who may have had responsibility for them.

Census taken by Jacques de Meulles in 1686. “Recensement des habitants de Chignitou, dit Beaubassin,” in Gagnon, Jacques, and Jean-Pierre-Yves Pepin, 2008. The still unmarried Marie Kessy, in her late teens, could also be included in this group.

My speculation as to why Marie-Josephe was unsupervised in the company of the Morin children.