Diamond Harbor 1877: Lost Anchors

When Quebec City was Irish

Was you ever in Quebec

Launching timber on the deck?

Where ya break yer bleeding neck

Riding on a donkey

— sea shanty

Quebec City was once an Irish town. Not majority Irish, but an Irish town nonetheless. Long ago the wealth of Quebec City lay in the port and the shipyards of the Lower Town, and its economic lifeblood flowed through the hands of the Irish who lived in its the coves and wharves.

Quebec City was built on timber. Vast Canadian forests of red and white pine were felled then floated down the St. Lawrence River on great rafts of logs. The flotilla ended at Quebec, where the rafts were torn apart and the logs loaded on fleets of ships bound for English shipyards and the insatiable maw of the British Empire.

Empty timber vessels returning to Canada were counterweighted with bags of sand or gravel that were dumped as soon as the ships got to port. The bags of gravel were soon replaced with hungry Irish. Many of the Irish stayed in Quebec to load the ships with more timber and to build more ships to carry still more timber.

Beneath the Citadel of Quebec there is a small strip of land between the cliffs and the river. Snaking along the shore was a long narrow road that started six miles upstream from the city, and ended at the Breakneck Stairs of the Lower Town. This road, called rue Champlain, connected a series of coves. The coves cradled booms that caught the floating timber rafts. Removed from the river’s current, the rafts could be pulled apart in the quiet water of the coves, and the beams loaded onto ships. The timber brought into these storage ponds made the coves natural shipyards. At one time, almost every male living in these coves was employed either loading ships or building ships.

The most famous of these coves was Wolfe’s Cove, now Anse-au-Foulon, the staging ground for General Wolfe’s daring assault on Quebec in 1759, when the British army scaled the cliffs to defeat the forces of Montcalm on the Plains of Abraham. Beneath the old battlefield the cliffs are studded with rock of glinting crystal. The cliffs once spat giant rocks, ice, or mud on the people who lived there, sometimes even burying them alive. The cove at the foot of these cliffs was called Diamond Cove. At one time there was a nest of wharves in this cove called Diamond Harbour, home to thousands of Irish ship builders, stevedores, dock workers, river pilots, and timber towers.

Irish started arriving in Canada long before the Famine. In fact potatoes had failed them many times before. Between 1828 and 1837 almost 400,000 people left Ireland for North America.

Sometime around 1830, the four Byrne brothers of Balyna, County Kildare, James, John, William, and Andrew, together with their elderly parents and their sister Mary, arrived in the port of Quebec in a returning timber ship.

The Byrne brothers’ father did not live long after arriving in Quebec. Eighty-year-old James senior died far from his fields in Kildare, but the parish burial record nevertheless recorded a life’s work: farmer. His children would spend the rest of their lives in Diamond Harbour. William and Andrew were ship smiths while John and James worked on the docks. Their sister Mary married George Boyce, a stevedore.

***

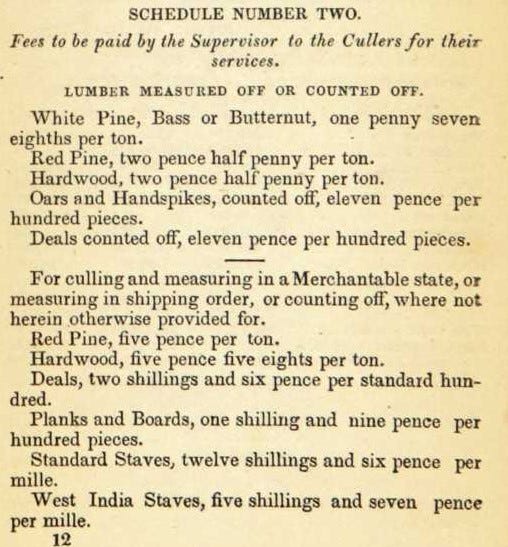

In the years before the Byrne brothers arrived in Quebec, sailors were supposed to discharge and load their ships. There was no more backbreaking or dangerous cargo than slippery, waterlogged timber. When sailors docked at Quebec they frequently absconded for higher paid work onshore or on other vessels. Deserters could hide in the many miles of coves and wharves along the shoreline, making it almost impossible for crimpers to find them. By the 1830s, onshore Irishmen in Quebec, called “cullers,” began replacing the sailors of timber ships who didn’t fulfill their contracts.1

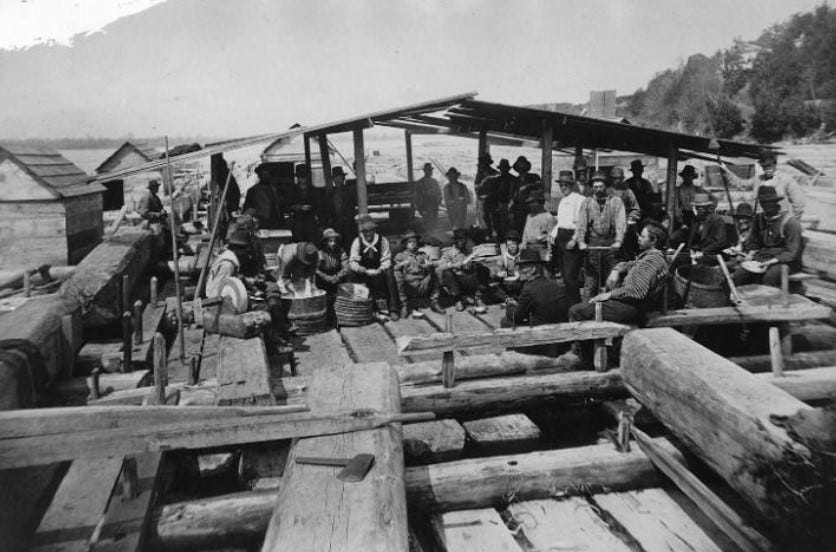

In other ports, men slipped in and out of work on the docks. Not in Quebec. No one could master loading timber in even a season of work. Every culler had some subspecialty, as a timber swinger, hooker-on, crocheter, wincher, or holder. Timber swingers soaked up to the waist or neck directed sixty foot lengths of floating wood towards the loading spot. The beams were fixed by hooks to a cable by a crotcheter or “boy on stage” so it could be moved by a crane operated by the wincher, and placed on the ship deck. The wood was then attached to another cable. The workers in the holds hung the wood on another crane to stack it. Ship laborers needed to know how to use leverage and pulley tools, as well as hooks and spikes to secure and direct water-soaked beams longer than a bowling alley.

Merchant shippers became highly reliant on stevedores to hire, train, and manage a swelling tide of unskilled Irish immigrant dock labor. Stevedores were also expected to defend against unemployed sailors commandeering or sabotaging any of this work. Most importantly, stevedores managed the logistics of loading a vessel. All tasks of ship laborers were carried out under the watchful eye of the stevedore who, with a stroke of chalk, determined the order of the logs to be stowed. The stevedore needed to measure and gauge the weight of the timber, know how to stack logs and pack them onto the ship for the most efficient use of space and optimized balance, and to be able to do this as quickly as possible.

***

It’s not known how James Byrne became a stevedore. On his arrival in Canada James was no doubt just another Irishman seeking work on the docks. Perhaps he had some latent skills in organizing and directing a gang of men. He must have had the good spatial reasoning and working memory required to load timber. By 1833 James was working as a river pilot. By the birth of his first child in 1835, he was identified as a stevedore. He was described by a priest at the birth of a daughter in 1844 as a timber “measurer,” one of the essential tasks of the stevedore.

James opened a tavern in Diamond Harbour, which through the winter was a source of income for him and entertainment for his cullers. The port of Quebec did not freeze as long or as deeply as Montreal, but timber was nevertheless a summer business. Starting in May, hundreds of rafts began arriving in the coves. Loggers spent all winter and spring cutting the great pine trees of the Ottawa Valley. The square timber then started its six week journey to Quebec, first on the Gatineau and Ottawa rivers in huge rafts of as many as 2000 logs tied together. On the rafts the men built birchbark cabanes or shanties where they slept and cooked. At night the raftsmen tied their floating timber islands to the giant trees that in those days lined the shores of these rivers.

The raftsmen were French and native men who knew how to run the white water. They split the rafts into cribs to stay within the clean tongue of the rapids, and guided the cribs through the seething water with thirty foot oars. The cribs were then joined together for the final stage of the journey down the Saint Lawrence.

The rafts bypassed the larger port of Montreal, which would have required an overland haul. Instead, the rafts floated onward down the river to Quebec, where they were caught at the booms, and met the timber towers who brought the logs into the coves, where the timber swingers began their work. Some enterprising raftsmen worked alongside the timber swingers. Some stayed the winter and repaired to James’s tavern to relax and spend their money.

***

In the spring of 1832, with the threat of cholera from overseas, the authorities opened a quarantine station a few miles downriver from the city at Grosse Ile to control the spread of the disease from immigrants. But on June 9th, the Mercury announced that cholera had arrived in the city. The epicenter of the outbreak was identified as a boarding house on Champlain Street, which had become infected by immigrants who had arrived the previous Thursday evening on the Voyageur. The city was soon overwhelmed. Tents filled with dying people covered the Plains of Abraham. The city roared with cannon fire—cannon smoke was believed to clean the air. Everywhere reeked of burning tar as people spread pitch in the streets and lit it on fire to stop the spread of infection.

Amid the chaos and the stink, the Byrnes’ mother Mary and their youngest brother Andrew died. Andrew was just twenty two years old. Mary and Andrew were buried in the Cimetière Saint Louis, which the city opened to consign the bodies of people who died of cholera, and later for victims of any other infectious diseases.

***

In November 1833 James married eighteen-year-old Mary Bell, the daughter of an Irish Protestant accountant and scrivener named Thomas William Bell. It is easy to guess how James and Mary met. Thomas lived and worked at 10 Mountain Street, the steep and twisty street that connects Quebec’s Upper and Lower Towns. The office was located directly across from the Neptune Inn, a well-known meeting place of cullers, shipmasters, and stevedores. 10 Mountain Street was also a meeting point where stevedores found and hired cullers. James’s signature on parish records has the sure, practiced penmanship of a literate person, but he may have sought out Thomas’s services in his contracting with shipmasters. It’s not clear how Mary was able to marry a Catholic and convert to his religion, except that her father had died the previous winter. Her younger sister Harriet soon also married a Catholic stevedore.

In 1837, James’s brother John joined his mother and brother in Cimetière St. Louis. Their sister Mary, along with her baby, died in childbirth in the spring of 1839. The following year, James’s last surviving brother William was laid to rest in Cimetière St. Louis. James was now without any of the family who had set out with him on the journey to Canada.

James raised a family with Mary in Diamond Harbour: three boys, William, Thomas and John, and two little girls and a boy who did not live past their second birthdays.

***

In 1847 100,000 sick and starving Famine emigrants passed through the quarantine station at Grosse Ile. Thousands of people on the island were killed by typhus, which soon reached Quebec City, where over a thousand people died in the spring and summer of 1847. Among the victims was James’s young wife Mary, aged thirty two, and James’s sister-in-law, Mary Ann Colgan, the wife of his departed brother William.

In the meantime, James had other troubles. In the new year of 1847, some five months before his wife’s death, James conceived a child with a woman named Mary McDonald. His son Michael was born in September that year. They married in 1850 shortly before the birth of their second child, Margaret. Mary and her children joined William, Thomas and John under James’s roof in Diamond Harbour.

***

The flood of Irish into Quebec City in the Famine years had tipped the balance between Catholics and Protestants in favor of the Catholics. Then, as ironclads began to replace wooden ships Quebec City saw the beginning of the end to its shipyards. Most of the shipbuilders, who lived in the St. Roch neighborhood, were Irish Protestants. They began to leave.2

In the meantime, the traffic through the port reached its height. Over 90% of North American timber flowed through its harbors. Logs from as far away as Kentucky found their way to Quebec so that American timber could evade British import duties. At the peak of the season, over six hundred ships could be docked in the port on any given day, with the coves filled with acre upon acre of floating logs.3

The Byrnes were now living in affluence in a brick home with their own live-in servant. By this time James, like other stevedores, had distanced himself from the laboring men of the port. Perched between the ship captains and the stowers, stevedores controlled the measure and count. They petitioned to incorporate to bargain collectively for fairer wages and better working conditions with merchants and ship captains, as well as prevent them from finding others to stow their vessels. The bill failed to pass, but stevedores persisted in the decades that followed while they consolidated more monopoly power over their laborers.

With a flood of Famine Irish now in Canada, competition for work on the docks increased. Stevedores not only hired the cullers, but also held the contracts to load and unload the ships. They bore the risk of the cost to load the cargo and so skimmed a portion of that cost before paying the laborers.

Stevedores competed with each other by price, driving down the wages of the dockworkers to protect their own profit margins. At the end of a job, the cullers were unemployed until the stevedore assembled a new group of men to load another ship. As long as the supply of cullers exceeded the available number of jobs, the stevedores had control over wages and working conditions, and had the power to blacklist a culler who tried to make trouble.

The cullers rebelled.

In the spring of 1855, British demand for Canadian timber suddenly cratered. Wages for men on the docks, never high, plummeted to less than half of what they had earned the previous season. The cullers, by now a tight knit community of mostly Irish seasoned timber stowers, decided to organize. The Committee of Ship Laborers, later the Ship Laborers Society, called out their grievance in the newspaper.

Two days later, they took it to the docks. Police were called to “arrest a gang of timber swingers who threatened to throw the stagers overboard for working under wages.”4 After several more days of strike action, shipowners agreed to a small increase in wages. The event was one of a number of protests by dock workers in North American cities in these years, and marked the beginning of a labor movement in Canada.

When the dock workers organized the stevedores were among the losers. Stevedores who aligned with the cullers lost contracts with timber merchants. Those who aligned with the timber merchants found themselves running afoul of the union. Many left the profession in the decades that followed. While previously there had been many French stevedores and cullers, the stevedores who remained were primarily Irish, and as a consequence, French dock labor was pushed out in favor of the Irish.

***

James founded a family business for the next two generations of Byrne men. His eldest son William became a stevedore, married the daughter of a stevedore, and lived on Champlain Street in Diamond Harbour his whole life. William’s early working years were the peak of the timber trade out of Quebec. As a middle aged man, William saw its decline as the British Empire began to source more timber from Scandinavia. The great wooden sailing vessels had by now been replaced by iron hulls. With the advent of the icebreakers and the growth of the railways, Quebec was eclipsed by Montreal as a port and logistics hub. Its port was only able to compete on the price of dock labor. Champlain Street became poor and rundown.

By 1895 the great timber rafts no longer floated into Quebec. With other cargo bypassing Quebec for Montreal, William began looking for an alternative to stevedoring. Together with six other men he founded the Quebec Coal Company, “for the purpose of trailing in all kinds of coals, bricks, cement, plaster, coal tar, clay pipes and other goods and wares of that kind.”5 William brought his experience in transportation and logistics to this start up. Sadly, William died of a series of strokes at the age of 58, mere months after the company was established.

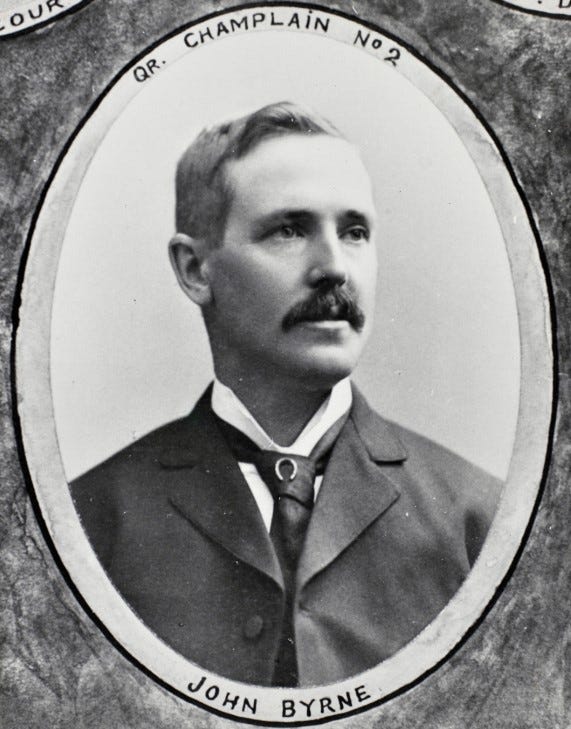

William’s son John Byrne moved out of Champlain Street as soon as his father died, but he remained in the family trade. His brief career in city government no doubt furthered his endeavors. John obtained contracts for all cargo handling for Grand Nord and other international steamship lines. In the 1920s he was Chief Stevedore for all Canadian Pacific Steamships out of Quebec and New Brunswick.

John’s death in 1930 brought a century of Byrnes on the Quebec docks to its end. His children followed the migration of the city’s Irish to other places.

***

One day in 1958, a Canada Steamship Lines cruise ship the S.S. Tadoussac passed through the old harbor of Quebec City. These cruises took American tourists from Montreal up to the Saguenay fjord. My father had a summer job as a purser on the Tadoussac. When the ship passed by the Citadel, its passengers stopped to gaze at the glinting cliffs of Diamond Cove. My father, the great-great grandson of James Byrne, could not see where his people had worked under the cliffs, or the great wooden ships or timber booms. There were no more harbors, no men on wharves, and no traces of the rolling, endless forest they had once stowed.

Fingard, Judith. “The Decline of the Sailor as a Ship Labourer in 19th Century Timber Ports.” Labour / Le Travail, vol. 2, 1977, pp. 35–53. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/25139896. Accessed 9 Dec. 2024.

Grace, Robert J. “A Demographic and Social Profile of Quebec City’s Irish Populations, 1842-1861.” Journal of American Ethnic History, vol. 23, no. 1, 2003, pp. 55–84. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/27501378. Accessed 20 Dec. 2024.

For a sense of the scale of this operation, just the lost rafts on the St. Lawrence accounted for one million feet of timber found on the coast of Anticosti Island in 1856. Mackay, Donald. The Lumberjacks. Natural Heritage Books, 2007.

Bischoff, Peter C. Les débardeurs au port de Québec: tableau des luttes syndicales, 1831-1902. Editions Hurtubise, 2009. p. 100.

Gazette officielle du Québec/Québec official gazette, No 18, May 4, 1895.

The unionizing of the Quebec ship laborers is a fascinating chapter in the history of Canadian labor movement. The definitive book on this topic is Peter Bischoff’s Les débardeurs au port de Québec: tableau des luttes syndicales, 1831-1902. Editions Hurtubise, 2009.

Your story catapults me into life in Quebec City, and it is amazing to learn about the depth of the Irish connection. Even today, more people from Northern Ireland, where I now live, emigrate to Canada than to the USA.

Ollie

Loved this piece. I had no idea about any of it and I lived in Quebec for five years! The port of Quebec was also, of course, the first landing place for immigrants to Canada, including many of my Scottish family connections.