One of my favorite sources for genealogical research is old city directories. Directories have told me so much about my family— where they lived, worked, and worshipped, and the people they lived alongside. I can dig into the urban history of the neighborhood. Addresses can also tell the story of social ascent or setback.

City directories can sometimes also reveal more personal stories. Cross-referencing Lovell’s Montreal directory and city tax rolls I was able to figure out that in 1865 my great-great grandmother had been evicted by her own father. The full story is here:

Montreal is a city of renters. Earlier generations of my family moved a lot. I don’t think they were alone in their restlessness. Apartment leases were annual, and it seems it was local custom to be always looking for better digs.

As a kid I was taught that the first of May was Moving Day. I am sure this was something my parents told me. If a person intended to move houses, it was supposed to happen on May 1st. I did not question the reason for this.

We moved away from Montreal and I did not hear anything more about Moving Day. There was no such day in any other place I lived. Moving Day never came up in conversation when I encountered other Montrealers. I came to believe that this was just our own family custom, and, since in most Northern places May 1st is the first day in the year that a landlord could legally evict a tenant, I guessed that I simply came from a long line of rent dodgers.

Some years later I learned that my family weren’t deadbeats after all, and there is indeed a Moving Day in Montreal. It’s now July 1st, which in Canada is a national holiday, but in Montreal it’s the day of schlepping.

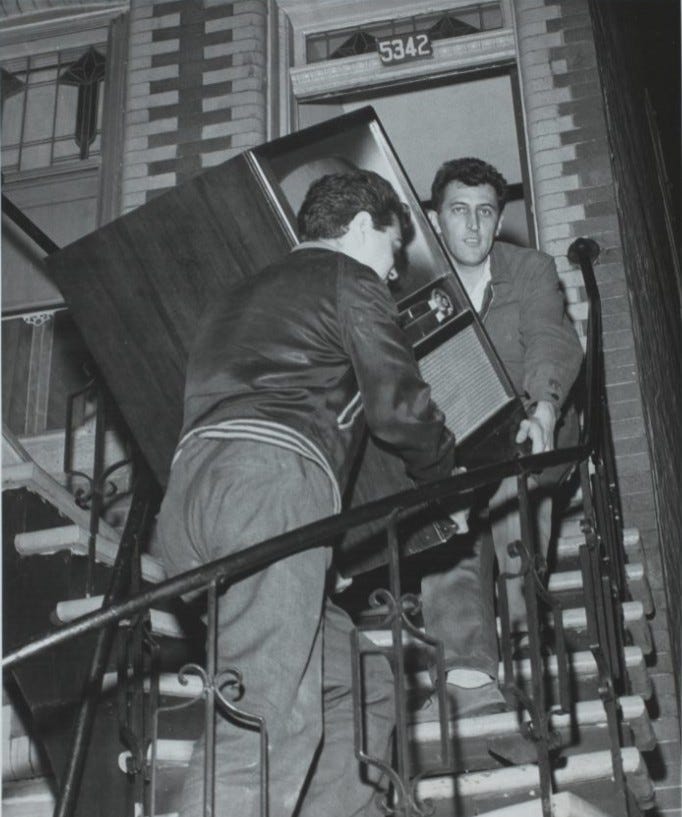

In a town of renters, when so many leases expire simultaneously, Moving Day is a massive, citywide relocation frenzy, with double-parked trucks on narrow streets and people hauling sofas up winding outdoor staircases. Much of the moving is done by amateurs with their worldly goods strapped with bungee cords to Subarus, because good luck getting a mover on the one day of the year everyone needs one.

My parents were correct: Montreal’s Moving Day had once been May 1st. Its origin was in the eighteenth century, when May Day in New France was the start date for many legal agreements, including residential leases, which were typically for one year. May 1st was codified in 1866 as the default date for lease expirations to protect tenants from being forced out of their homes in winter. In 1975, the Quebec government amended the law to move apartment leases to July 1st, to prevent disruption for children during the school year. And since July 1st was also national holiday, it gave everyone a day off work for moving.

I was surprised to learn that the tradition of Moving Day was not unique to French Canada. Moving Day existed in many American cities beginning in colonial times, when there was a designated day when all residential leases in a city expired simultaneously. In most places, this was on the first of May.

British visitor Isaac Fidler observed Moving Day in New York City in 1832, while also predicting our future appetite for HGTV:

It is almost impossible to rent a house or lodgings longer than for one year; and in any part of a year longer than till May-day next ensuing… in every direction were carts and waggons laden with furniture; the streets were literally tilled with chairs, tables, draw, desks, carpets, &c, passing from one house to another, to the great advantage of the carters, who find full employment, and are on that day paid double charges. It is also not a little gratifying to New York gossips, who are allowed a peep into the lodgings of such strangers generally as have not permanent dwellings. As May-day approaches… the tenant finds, or the most part, an advance of rent, and prefers a change.. the tenant commences amusing himself with entering every one's dwelling similarly circumstanced, and exposing his own to the gaze of others. It is almost impossible for a stranger, who has occupied lodgings, and wishes to escape imposition, to avoid such intrusion into his private rooms. We suffered this ourselves, and therefore speak from experience. Many American women, we were told, occupy much of their leisure time about this period in prying into the abodes of foreigners, to see if they are respectable, and have their rooms well furnished. Americans could not have invented any domestic custom more inquisitorial, or which gives a readier access to the privacies of stranger.1

Thousands of people changed their residences in the city, causing traffic chaos. The New York Times described the chaos of the Moving Day of 1856 in Manhattan:

“It will begin early—before some of us are up, no doubt, and will continue late. The sidewalks will be worse obstructed in every street than Wall Street where the Brokers are in full blast. Old beds and rickety bedsteads, handsome pianos and kitchen furniture will be chaotically huddled together... Bed screws will be lost in the confusion and many a good piece of furniture badly bruised in consequence. Family pictures will be sadly marred, and the china will be a broken set before night, in many a house.”2

By the early 20th century, it was estimated that as many as one million New Yorkers moved in a 24 hour period. Moving Day was known as a “cartman’s feast.” Any farmer with a wagon to rent could charge any price he pleased. Many New Yorkers had to pay as much as a week’s wages to move.3

It’s astounding that the insanity of everyone in New York moving the same day continued as long as it did. The practice disappeared in American cities in the twentieth century, as tenant protection laws reduced some of the real estate musical chairs, as well as more standardized legal lease agreement, which allowed for customizable lease terms beyond the traditional vacancy date. Landlords realized the benefit of staggering their lease terms. In New York the advent of rent stabilization and rent control regulation discouraged tenant turnover. Widespread tenant protections had the same impact in other cities.

But of course the people of Quebec always demand le droit à la différence. So the madness of Moving Day continues with an estimated 100,000 people moving on or around July 1st each year. There seems to be a perverse pride in keeping this tradition. In the collective imagination it is some sort of amateur community-bonding experience, with the notion that people can help their friends and neighbors because all the movers are booked.

People in the United States and Canada have a history of extreme mobility. Urbanization and westward expansion meant that much of this movement was over long distances. In the 19th century, about a third of people were living in a different town from where they were born. In looking at these old directories and phonebooks, I can trace my restless Maguire family moving from one home to another—but all within the same city.

In the 1800s the Saint Lawrence River regularly flooded the low-lying immigrant neighborhood of Griffintown, sending residents fleeing their homes to drier ground. People moved in and out of different flats and storefronts each spring. The first generation of my family in Montreal took part in this annual Mad Tea Party of real estate, sometimes moving to another street only to return to the same address the next year. Later, as the upwardly mobile Maguires began their long, slow climb up Montreal’s mountain, they changed addresses frequently.

People had fewer possessions in the nineteenth century, and many homes came furnished. Moving could have been accomplished in a single trip with a drayman and a cart hired for the day. But the streets would have been grid-locked with everyone moving at the same time. Getting to a new crosstown address would have taken an hour or more. Even with assistance, the Maguires would have had to carry many of their belongings, breakables wrapped in blankets and clothing, up those outdoor staircases, often in a May snowstorm. I can’t imagine what Moving Day must have been like for a very large Irish family with many small children.

The Maguires remained itinerant until my grandparents married, in 1933. They remained at the same address until 1954, when they bought a handsome brick house in Outremont and finally ceased to be renters.

In memory of the Maguires of 44 Colborne Street, 184 Nazareth Street, 103 William Street, 48 Shannon Street, 104 Shannon Street, 106 Shannon Street, 77 Ottawa Street, 188 Ann Street, 477 St. James Street, 146 Mitcheson Street, 13 Tara Hall Avenue, 11 Lafonte Avenue, 147 Mont Royal Avenue, 151 Mount Royal Avenue, 40 Querbes Avenue, 5636 Canterbury Avenue, and 19 Robert Street.

Isaac Fidler, Observations on Professions. Literature, Manners, and Emigration, in the United States and Canada, Made During a Residence There in 1832. London, 1833. Quoted in Gold, David L. "Moving Day in Old New York City: A Custom of Dutch Origin?" de Halve Maen (Spring 2007). LXXX (1): 9–14.

New York Times, “Moving Day,” May 2, 1856

Marjorie Cohen, “Believe it or not, May 1st was once moving day for the entire city,” Brick Underground, May 1, 2018. https://www.brickunderground.com/live/may-moving-day Accessed February 11, 2025.

Astonishing, and a great read. I was bought up in a house in a small village in Scotland, built by my ancestors in the 18th century. It was not until I was an adult that I realised that people bought and sold houses, let alone the complexities of renting! In our part of the world you either had a family house that you lived in, or your house came with the job e.g. gamekeeper.

I really enjoyed this, Lisa. FWIW, growing up playing golf, "Moving Day" was associated with the Saturday third round at the Masters tournament in Augusta, GA, one of the four "major" tournaments. I've known my own version of "moving day" just shy of 40 times in my almost 71 years. Haven't looked up the dates yet, but I wonder if the 19th-century US census enumeration periods took moving day into consideration.