In the winter of 1688, my Morin ancestors were expelled from their village of Beaubassin, Nova Scotia. They walked into the Canadian wilderness taking only what they could carry. The exile of the Morins is an Acadian legend. But to know why they were banished begins with the village of Beaubassin—a story of rebellion, a witch trial, and forbidden love.

The previous installment may be found here:

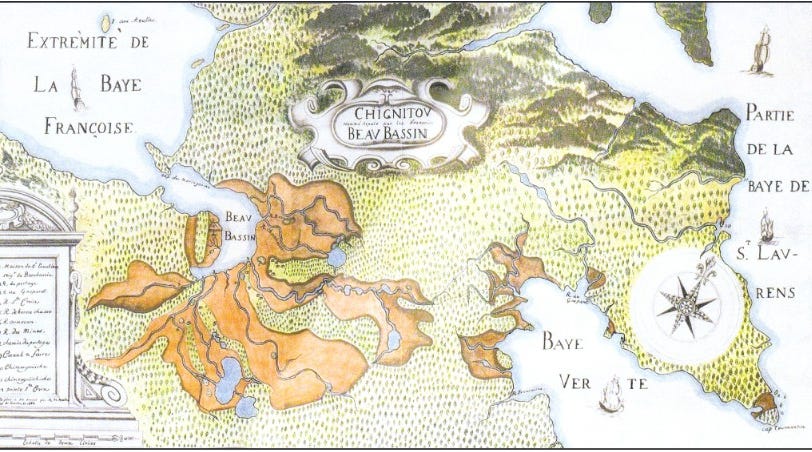

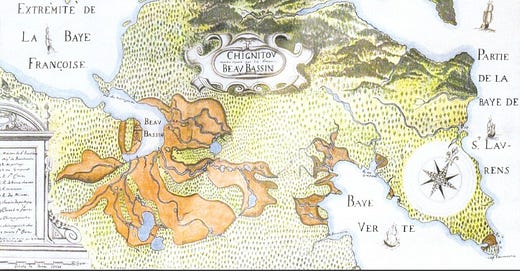

The story so far: In 1671 Jacques Bourgeois, his sons and sons-in-law, establish a new settlement of Beaubassin in the marshlands where Nova Scotia meets New Brunswick. They are soon joined by others seeking independence, including Pierre and Marie Morin. Everyone is engaged in back breaking work of draining the marshes. Then, in 1676, Beaubassin is granted to Michel Le Neuf as his noble fiefdom. To drain the marshes, Le Neuf imposes his feudal right of unpaid labor, the corvée, which the villagers refuse. Le Neuf finds a source of labor in the problematic Jean Campagna. Le Neuf takes the villagers to court to impose the corvée and loses. Le Neuf returns from his failed governorship in Port Royal to a village outraged by Campagna. Le Neuf arrests Jean Campagna for witchcraft. There is not enough proof to convict Campagna, who goes free. The Morin family grows close to Le Neuf. In 1687, when Le Neuf is away, the Morins’ oldest unmarried son Louis falls in love with Le Neuf’s young daughter. Le Neuf returns to Beaubassin to discover she is pregnant.

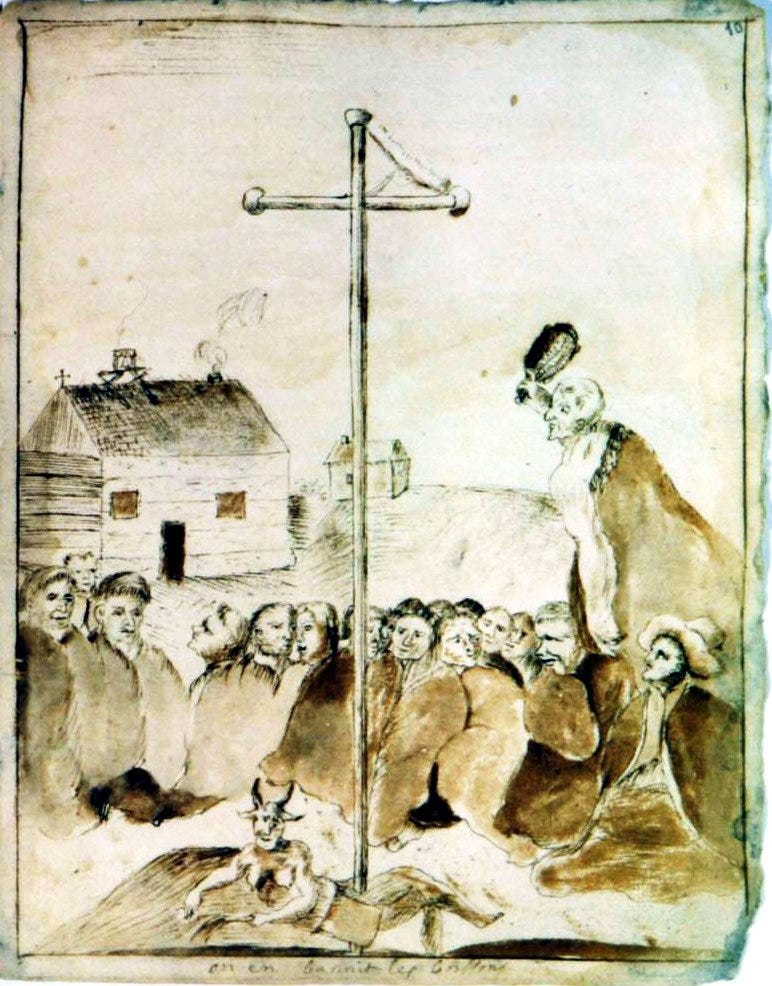

Abbé Claude Trouvé had been warned by his Bishop that the people of Beaubassin were behaving in ungodly ways. The villagers were drinking and consorting with savages. Trouvé had been told there were Christians among the Mi’kmaq, but the villagers did not seem to care to distinguish between those who had accepted Christ and the godless heathens.

Despite the Bishop’s warnings, Trouvé had arrived unprepared to manage this business with the Morin boy and the seigneur’s girl. Such licentiousness no doubt came straight from there being no priest, a lot of eau de vie, and ongoing commerce with the savages. The Morin boy would be made an example of for the others to renounce their sin.

Trouvé called on the family to hear Louis’s confession and give penance, but the boy had been hiding in the marsh ever since the news broke.

Trouvé had scarcely returned from the Morins when Le Neuf turned up at the priest’s door with a face full of thunder. I will run that wretch through with my sword when I find him. No man on this earth would judge me for it.1

Trouvé told Le Neuf that if no man would judge him, God would. There was no need to take a life. Better to seek a way to get justice without breaking a commandment. We can punish the boy and demand compensation from the family, said Trouvé. 2

Le Neuf relished the idea of slicing up Louis Morin, but he knew it was impossible. But he would exact his pound of flesh from the Morin family one way or another. As seigneur, Le Neuf was the local court. The priest would be able to pass on God’s judgment. Between them, they would make the Morins pay.

Pierre and Marie Morin called on Le Neuf at Ile de Vallières to plead on behalf of their son. The Morins said that Louis was willing to marry Marie-Josephe. Le Neuf just laughed at this.

Once they had gone, Le Neuf sent for Trouvé. The boy would be put on trial. Testimony would need documented for the court. Trouvé declared this was impossible. Monseigneur was not a disinterested party. He could not be impartial.

That’s why you are going to do this, said Le Neuf. Trouvé looked at him disbelief.

You will take the depositions and this testimony will confirm his guilt. Then we will have to send him to Quebec, given the severity of the charge.

What is the charge? asked Trouvé.

Seduction.

Trouvé dutifully recorded the testimony of witnesses who confirmed that Louis Morin was the father of Marie-Josephe’s baby and no one else.

Louis Morin has taken advantage of an innocent girl and flouted the authority of a father and his seigneur, Trouvé told the villagers at Sunday Mass. He will face justice in this world and the next.

It was already autumn and too late in the season to travel to Quebec. Le Neuf could not keep the boy in the bakehouse all winter as he did with Campagna. There were simply too many people in the village who liked the Morins and would let the boy escape. He had to remove Louis Morin from Beaubassin immediately.3

Trouvé suggested that Le Neuf send the boy to Port-Royal instead. As the local magistrate, Le Neuf could not be seen as impartial, but the Governor of Acadia could decide what to do with him.

I will offer my own suggestion, said Le Neuf, pantomiming slicing his throat.

Trouvé went to the Morins and said that if Louis gave himself up he would be judged by the Governor in Port-Royal. The Morins were relieved. No one knew the new Governor of Acadia, Louis-Alexandre des Friches de Menneval, who had only just arrived at his post, but he had to be more reasonable than Le Neuf. Louis came out of the marsh and gave himself up to Trouvé, who on orders of Le Neuf had him put into leg irons and imprisoned in the village bakehouse.4

Only then Trouvé told the Morins that he intended to charge Louis with seduction. The Morins were horrified. Seduction was potentially a capital crime.5 Trouvé had betrayed them.

Louis was marched to Port-Royal into the custody of Menneval. The Morins waited for weeks to learn the verdict. When the news came, they were devastated.

Trouvé read aloud Meneval’s letter to Le Neuf to the gathered villagers.

Louis Morin has committed a serious crime and in my view he deserved an even harsher punishment than usual because his offense was committed against an important family. I expect the proposed punishment meets with your approval as it is the most practical solution under the circumstances, given that there are no executioners nor a royal prison here in Acadia. It is moreover dangerous to leave him here in the country and there are no means to send him to Quebec. For this reason, I have decided to send Louis Morin to France on the return voyage of the Friponne.6 He will make a good sailor and serve the King well.7

The Morins knew they would never see Louis again.

Next, Le Neuf told Trouvé what he should get in compensation. You will tell the village that you are passing sentence on the Morins and this is what you have decided.

And what is that Monseigneur? asked Trouvé.

Everything. The land, the animals. All of it.

Trouvé looked at him. How will they live?

Tell them, said Le Neuf.

Trouvé announced to the assembled village that he had made a decision regarding the compensation that the Morins owed Le Neuf for Louis’s crime. Pierre and Marie Morin would give Le Neuf the sum total of their property, based on the last recensement from Monsieur de Meulles, which was thirty arpents of land,15 cows, 8 sheep, and 12 hogs. 8

Marie and Pierre stood frozen in shock. Le Neuf was taking everything.

All the toil of the prior decade flashed before their eyes: Years of standing in the hot sun, knee deep in muck, digging trenches. Pulling a breached calf out of its mother in the dead of night. Wrapping tender apple saplings in canvas in a late spring snowstorm. Bending over row upon row of puny wheat year after year. It was all gone. They would need to leave, lease themselves out to some other seigneur, and start all over again.

There were rumblings in the crowd. Michel Chiasson, brother-in-law of Pierre Morin fils, yelled out: What kind of priest are you? Who are you to deliver legal verdicts and award financial damages? You are not the magistrate. Where is Monseigneur?

Jacques Cochu, husband of the Morins’ daughter Marie, shouted: Why don’t you stick to God’s judgments? 9

In the weeks that followed, the chorus of outrage in the village grew louder. Who was this outsider adjucating legal cases and passing sentences on the Morin family? This priest was an interloper in this village and he knew nothing. Le Neuf was hiding behind his priest.

But the protest was all from the same quarter: the Morin clan. The Merciers and the Kessys, still in Le Neuf’s good graces, did not dare speak out against Trouvé. The Bourgeois faction was silent. The Morins had long ago made their bed.

The men of the Morin clan discussed what to do. We need someone to help us write to the Governor. To the Bishop. There are too many of us in this family to arrest. There are not enough men to do the work without us. If we band together…

Meanwhile, Trouvé told Le Neuf that he would not tolerate any more of the defiance that marked the last village gathering. All the troublemakers needed to leave. Not just Pierre and Marie Morin, but the whole family. Every last one of them.10

Le Neuf agreed. He wrote to his in-laws, the Denys family, to inform them of the decision to expel the Morins. Henceforth, this troublesome family would be their problem. 11

In the new year of 1688, Pierre and Marie Morin, their young children, together with the adult Morin children Pierre, Marie, and Anne, Pierre’s wife Françoise Chiasson, Marie’s husband Jacques Cochu, Anne’s husband René Deneau, all their children, and accompanied by Michel and Jean Chiasson, set out into the wilderness on snowshoes, pulling sleds piled high with their possessions. More possessions and little children were strapped to their backs. They set off through the upland woods, leaving the marshes behind them.

Where could they go? The Morins were banished from all settlements in Le Neuf’s domain, which was almost all of Chignecto. There was no returning to Port-Royal. The only place they could reach on foot was the Mi’kmaw village of Listuguj (Restigouche) on the Baie des Chaleurs, the southern coast of the Gaspé peninsula. The settlement was part of the domain of Le Neuf’s brother-in-law, Richard Denys. It was several weeks’ journey and there were no European people living there—Denys used it as a summer fishing camp. It would be months before Denys would even know they were there.

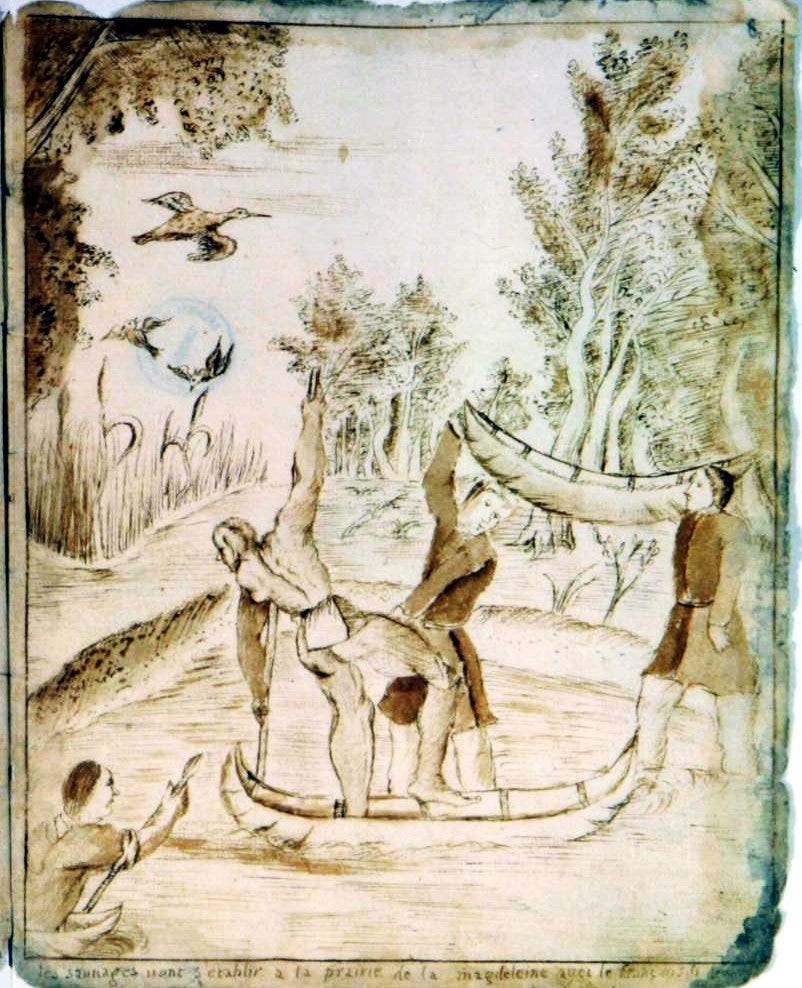

The Mi’kmaw residents of Beaubassin told the Morins that they knew the people of Listuguj. They were trustworthy and traded with the French. Some spoke their language. The Mi’kmaq arranged for a few of their own people to accompany the outcasts as far as the Baie des Chaleurs, since the Morins did not know the country between Beaubassin and Listuguj. 12

And so the Morins walked to Listuguj, following Mi’kmaw portage trails through the dense forest. Snowpack and frozen river crossings made some of the trek easier, but the group moved slowly, weighed down by belongings and little children.

Pierre and Marie had a lot of time on their walk to recall the series of improbable events that led them to ally with Michel Le Neuf. And to think about why the other villagers had been silent and simply watched them go.

When the Morin clan arrived in Listuguj, Pierre was exhausted from the journey. He died in Listuguj, still waiting for a letter from Quebec that would give them permanent refuge.

Back in Beaubassin, Le Neuf took possession of the entire Morin clan’s property, including over 40 arpents of land, bringing his own property to over 100 arpents. He enlarged his personal animal stock by 18 sheep, 26 pigs, and 29 cows.

His priest had done a good day’s work in the righteous service of the Lord.

Next: Epilogue

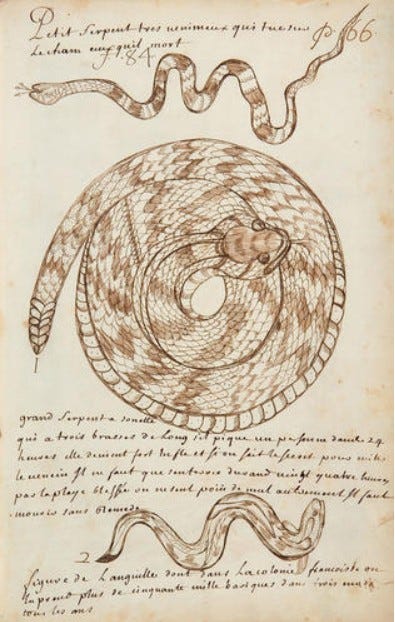

The drawings are by Claude Chauchetière, a Jesuit missionary among the Iroquois and the Kanien'kehá:ka (Mohawk). His Annual Narrative of the Mission of the Sault from Its Foundation Until the Year 1686 documented his time ministering to the native people.

Chauchetière is perhaps best known for having encountered Kateri Tekakwitha, a Kanien'kehá:ka Jesuit convert, in his mission work at the village of Kahnwake near Montreal. Chauchetière’s recognition of her eventually led to Kateri Tekakwitha’s canonization as the first indigenous Catholic saint.

This was Le Neuf’s go-to threat, according to the deposition documents of the Campagna witch trial.

All conversations between Le Neuf and Trouvé are my imagining based on what appears to have been a coordinated effort to punish Louis Morin and his family.

This is my guess why Louis Morin was sent to Port-Royal. As we have seen in the case of Jean Campagna, serious offenses required at least judicial review in Quebec and this procedure was not followed here. They needed to get rid of Louis Morin.

Louis Morin would have had ample opportunity to hide and escape. He would have had to have been taken in custody willingly. Perhaps due to pressure on his family.

Seduction was a serious offense in the ancien régime, as it was not only a crime against morality, but a crime against parental authority, and, in the case of unsanctioned marriage, potentially a crime against property. The sequence of events is my imagining.

The name of this Royal frigate translates as “the Rogue.”

This letter paraphrases the actual report that Menneval sent to colonial authorities about his decision on the matter.

From the census taken by Jacques de Meulles in 1686. “Recensement des habitants de Chignitou, dit Beaubassin,” in Gagnon, Jacques, and Jean-Pierre-Yves Pepin, 2008.

This scene is based on the oft-repeated story that Trouvé expelled the entire Morin clan because the sons-in-law had spoken out against him. I cannot find any primary source that confirms this, however.

same as above

We don’t know how Richard Denys came to host them in Restigouche. It’s possible Le Neuf arranged it, or that the Morin family simply showed up there having no other destination reachable without a boat. I would think that once their destination was known, Le Neuf would have to write to his in-laws to explain how his tenants ended up in the Denys domain.

It would have been virtually impossible for them to have made the trip without local people familiar with the route.

This is great!

When the epilogue is in, I'd like to share your whole story with several groups I belong to. Okay with you?

Interesting to read that the charge of seduction was an offense to parental rights. So well-researched! Looking forward to reading the Epilogue.