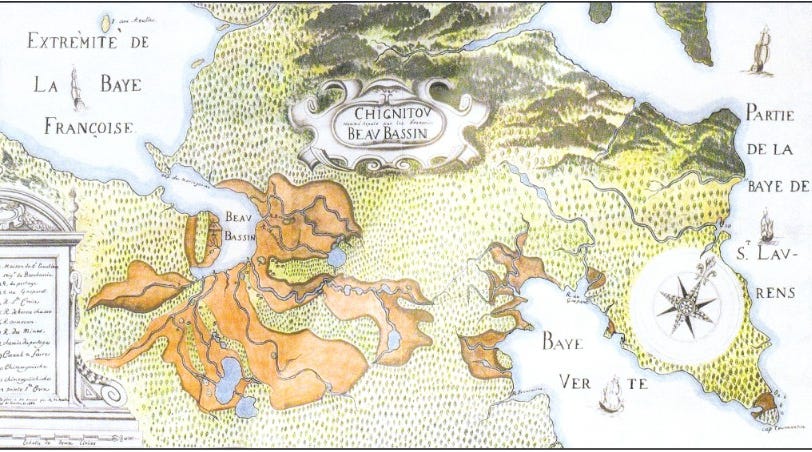

In the winter of 1688, my Morin ancestors were expelled from their village of Beaubassin, Nova Scotia. They walked into the Canadian winter wilderness taking only what they could carry. The exile of the Morins is an Acadian legend. But to know why they were banished begins with the village of Beaubassin—a story of rebellion, a witch trial, and forbidden love.

The previous installment may be found here:

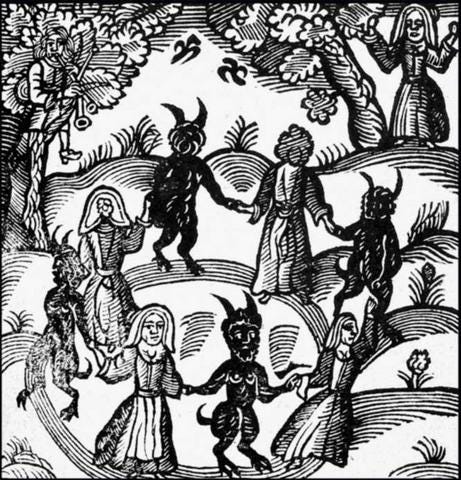

In this installment: Jean Campagna is accused of witchcraft

The story so far: In 1671 Jacques Bourgeois, his sons and sons-in-law, establish a new settlement of Beaubassin, in the marshlands where Nova Scotia meets New Brunswick. They are soon joined by others seeking independence, including Pierre and Marie Morin. Everyone is engaged in back breaking work of draining the marshes. Then, in 1676, Beaubassin is granted to Michel Le Neuf as his noble fiefdom. To drain the marshes, Le Neuf imposes his legal feudal right of the corvée, enforced labor of the villagers, which the villagers refuse. Le Neuf finds a source of labor in the problematic Jean Campagna. Le Neuf takes the the villagers to court in Quebec to impose the corvée and loses. Le Neuf returns from his failed governorship in Port Royal to a village outraged at Campagna. Le Neuf finds a solution to several problems with the arrest of Jean Campagna.

In September Jean Campagna was arrested, shackled, and imprisoned in the village bakehouse. Le Neuf had built a communal oven which, like the mill, was his own personal concession that the villagers had to pay to use. The bakehouse was a perfect jail. Its walls were strong enough to hold the enraged Campagna, and it was insulated enough that the village could ignore his ranting and pleas for mercy.

Le Neuf told the villagers that witchcraft was a crime beyond his jurisdiction and Campagna had to be tried in Quebec.1 He would stay locked up in the meantime.

Campagna spent ten months in the bakehouse as Le Neuf’s prisoner.

For a few months, Le Neuf mulled over the case. As the local law court, he was obliged to undertake fact gathering before taking it to the royal court in Quebec, so he needed to record testimony from Campagna’s accusers. With the exception of Andrée and her sister Marie, no witnesses were in a hurry to make formal statements. It was winter before Le Neuf got depositions from others.

Le Neuf deposed Andrée and Marie immediately after Campagna’s arrest. Andrée repeated the story of how she stopped Campagna from molesting a young girl in Port Royal. She also volunteered that she’d once seen Campagna upriver with a band of fellow witches, but did not identify who his companions were.

She recalled how when her husband François Pellerin and Campagna were working together on the marsh, Campagna breathed into Pellerin’s eye. Her husband was dead of a fever a few days later. And this was not the end of his witchcraft. Campagna had been in her house the day her husband died, and it was clear to her now that he had cast a spell to finish him off.

That night Campagna took out a mysterious box and put at her husband's feet. Pellerin was convinced that Campagna was up to no good. When he saw the box at the foot of his sickbed asked Campagna to remove it. Then Campagna said this strange thing: “It’s good for grinding barley.” What did that mean? No one knew.2

Marie Morin testified that she’d heard that Campagna once tried to kill a man in Port-Royal, and told the story of how Campagna had enchanted and killed Madame Le Neuf with his gift of butter.3

The women were deposed without Campagna present, but Andrée’s husband Pierre Mercier was made to go the bakehouse to testify in front of Campagna. He was now pathetic to see, confined to a tiny, stifling room and hobbled by leg-irons.

So Pierre, you are not finding me in the best shape right now, said Campagna.

Pierre was unmoved. Well, it’s good for grinding barley, he replied with a shrug.

What do you mean by that? asked Campagna

I don’t know. You tell me why you said it to Pellerin the night he died.

Campagna searched his memory. Oh, that. It’s something I heard that you can say. It’s just a joke.

Do you remember when you said that you would wager that I would never bed my beloved Huguette?

Who told you that?

I can find witnesses.

Campagna denied everything.4

This scene was repeated over the months that followed. Villagers were brought to the bakehouse to record their accusations in his presence.5 Campagna had no proof of his innocence, no alibi, no witnesses.

Jean-Aubin Mignaux recounted François Pellerin’s last night alive. And he retold the story of Campagna cursing his fields, saying they would yield nothing. It’s not a curse if you tell someone to his face that he’s a bad farmer, said Campagna.

In the meantime, Le Neuf told everyone he’d written to Quebec, but he could not take Campagna there since it would soon be winter and the route to Quebec impassible.6 Campagna’s transfer to the Royal Prison had to wait until spring, when it was certain that the rivers and portages were clear of ice and snow, which in New France was not until May.

By winter the villagers were sick of Campagna occupying the bakehouse, and of having to draw straws to bring him food and take away his pot de chambre. Campagna heaped abuse on anyone who entered, protesting the injustice of it all. He had no one to speak for him, no one to refute any of the accusations. All he could do was say they’re lying.

Meanwhile, Le Neuf continued taking depositions from his witnesses.

Pierre Godin told the story of the night that he and Campagna were staying at the Kessys, and as they sat by the fire Campagna touched Godin’s belly. Godin immediately had terrible pains in his innards, and started vomiting. It was only when Monseigneur Le Neuf threatened Campagna that he, Godin, got better.7

All three Kessys told the story of their fight with Campagna, and how their cows had got sick, and how they had not been cured until Father Moreau blessed them and Monseigneur Le Neuf threatened to kill Campagna.8

Andrée’s daughter testified that when she heard about the Kessy cows she had declared that if that witch Campagna ever tried to kill her father’s cows, she would burn him. Later that very day, walking in the bush some miles away upriver, Jean Campagna appeared in front of her on the path and said: So you came to burn me as a witch? Where is your wood? When she asked how he knew this he just said: I have good ears.9

Le Neuf’s pilot Jacques Cochu, married to Pierre and Marie Morin’s daughter Marie, said that he’d heard from his father-in-law Pierre that Thomas Cormier had touched Campagna’s scythe and had felt ill ever since. 10

Each deposition was taken in the presence of a third party who was witness the accuracy of the testimony and co-signed the marks made by the accusers. These co-signers do not appear elsewhere else in any Acadian historical records.

One unbidden witness came forward to the annoyance of Le Neuf. But he could not come up with a reason to refuse the unsolicited testimony of Germain Bourgeois, who was at Pellerin’s bedside the night he died.

Bourgeois reported that Pellerin in his last hours was mad with fever and obsessively cursing Jean Campagna. Even though Campagna had left the house, Pellerin thought he saw him sitting by the fire. The dying man kept raving and hallucinating Campagna, saying look at that hideous man over there, isn’t he ugly?

As far as the Bourgeois faction were concerned, witchcraft allegations from the extended Pellerin family were the product of feverish paranoid ravings of a dying man. And, in case there was any remaining doubt, they were now certain that the Merciers, the Morins, and the Kessys were firmly in the camp of Le Neuf.

As he collected the testimony, Le Neuf was marking time against the spring day Campagna would be escorted from Beaubassin. Unlike Granfontaine, he couldn’t just send him to Port-Royal with a letter.11 He had to be sure that there was no way for Campagna to return. And anyway, these yokels wanted justice. Getting rid of him this way was a bit more complicated but no more of a problem than pulling a rotten tooth.

Le Neuf was not a jurist, but he knew something critical to the fate of Jean Campagna: Anyone in New France found guilty of witchcraft was condemned to banishment rather than death. Banishment was all Le Neuf needed. It was a salve to his conscience that whatever happened in Quebec, he, Le Neuf, was not sending a man to hang.

In the spring of 1685, Le Neuf’s nephew Simon-Pierre Denys and a shackled Campagna set out for Quebec. The men arrived in June. Campagna was immediately taken into custody in the Royal Prison and indicted for malefice et sortilège. Curses and spells.

Next: Campagna on trial

In France witchcraft was a capital offence, and for this reason the accused had the right to appeal to the provincial parlement. This practice was replicated in New France, where the local seigneur, who could only mete out justice for lower level criminal cases, had to refer such a case to the procureur in Québec.

Deposition of Andrée Martin, Gagnon, Jacques, and Jean-Pierre-Yves Pepin, Un sorcier en Acadie: Transcription annotée des minutes d'un procès et document contemporains 1684-1686, Les Éditions historiques et généalogiques Pepin, 2008.

Deposition of Marie Morin, Gagnon, Jacques, and Jean-Pierre-Yves Pepin, 2008.

From the deposition of Pierre Mercier, Gagnon, Jacques, and Jean-Pierre-Yves Pepin, 2008.

Confrontation, unknown in English and American common law, is a legal procedure and part of the pre-trial fact gathering under French law. It serves as part of the pre-trial fact gathering that is part of the investigation phase of a legal case. Not unlike the American and English cross-examination at trial, confrontation is a process for truth finding in which the accuser and accused are questioned in each other’s presence.

Since the arrest of Campagna occurred in the fall, it seems likely that unless Le Neuf moved extremely quickly to take the depositions, he would miss the opportunity to travel to Quebec before winter. It seems that he made use of all this time to establish the case before committing anything to the official record. We can only speculate why he waited until February to do this. My best guess is that he was refining the testimony with the witnesses.

Deposition of Pierre Godin, Gagnon, Jacques, and Jean-Pierre-Yves Pepin, 2008.

Depositions of Roger Kessy, Marie Poirier Kessy and Marie Kessy, Gagnon, Jacques, and Jean-Pierre-Yves Pepin, 2008.

Deposition of Isabelle Pellerin, Gagnon, Jacques, and Jean-Pierre-Yves Pepin, 2008.

Confrontation of Thomas Cormier, Gagnon, Jacques, and Jean-Pierre-Yves Pepin, 2008.

See the second installment of this series that tells the story of how Hector de Granfontaine had Campagna removed from his colony and sent to Port-Royal.

Once the accusation is made, there can be no other convincing explanation for what happened in the past. The tension mounts and so do witness statements!

What a gripping story Lisa! I think I will have to go back to the beginning and read it from the start