Montreal 1878: Boyne's Red Shore

At nine o’clock in the evening, July 12, 1691, near the village of Aughrim, Galway, under heavy rain, an army of Catholics loyal to King James broke ranks and fled before the forces of Protestant William of Orange. The Jacobite cavalry turned and rode for Loughrea, while their Irish infantrymen could only escape into a nearby bog. The foot soldiers threw down their weapons to run faster. The pursuing Protestant cavalry cut them down in the dark. Their bodies were left unburied.

The disaster of “the Twelfth” marked the start of Protestant absolute rule in Ireland. The Orange Order was later formed to defend Protestant privilege against the Catholic majority. For centuries after the defeat, the Orange Order observed the Twelfth to commemorate the victories at Aughrim and the Boyne with triumphalist parades celebrating Protestant domination in Ireland and elsewhere.

The Irish began immigrating to Canada in the early 19th century, bringing their sectarian allegiances with them. The Orange Order, a fraternal organization that fostered business and political connections, continued to embrace its twin ethos of loyalty to the English king and anti-Catholicism. Its more militant youth groups, such as the Young Britons, also engaged in street demonstrations and recreational street fighting with Catholics.

The Irish Famine sent two million mostly Catholic immigrants to North America. Irish Protestants became a small island in a Catholic ocean. The Fenian Brotherhood, an armed Irish republican group based in the US, attacked military fortifications and other targets in Canada in 1866, 1870, and 1871. More Orange lodges sprang up in cities everywhere, rising on a tide of nativism. By the 1870s, there were over eight hundred Orange lodges in Canada and twenty Orange newspapers. Orangemen filled the judiciary and controlled many public institutions like the Post Office and the Custom House. Orangism became so widespread that the Twelfth was a municipal holiday in Toronto to allow city workers to march in the parade.

Religious and political processions occurred throughout the calendar year, but there can be no mistaking why the Orange Order chose to parade on the Twelfth: 1) to harass and intimidate Catholics, and 2) make them riot. Control of political machines in some cities gave Orangemen some immunity from the law and a monopoly on “legitimate” violence against Catholics. Most Catholics stayed home on the Twelfth, and kept their children indoors. But enough ventured out to attack the parades. In 1870 and 1871, the Orange Order of New York City held July marches, with riots killing over sixty people. In Canada, Orange parades in Toronto and other towns invariably ended in bloodshed.

Con Maguire arrived in Canada with his family from Ireland in 1864 as a ten-year-old boy. The Maguires came from the predominantly Catholic town of Omagh, Tyrone. For Con’s family, it must have been a relief to settle in Montreal, where Catholicism was enshrined in law and there was none of the sectarian violence that plagued other Irish communities. By 1870, the Orange Order had been banned in Quebec. Catholics and Protestants had lived side by side in peace in Con’s Griffintown neighborhood, despite Irish Catholics outnumbering Protestants of all denominations 2:1.

Then, in 1876, a Methodist pastor in Montreal began falsely claiming from the pulpit that Catholics had been crowding Protestants out of public sector jobs, and the Church was redistricting electoral boundaries in its favor. On July 12th, 1876, the Grand Orange Lodge of Montreal decided to march. Catholics attacked the Orangemen, and the day ended with arrests for fighting.

In April 1877, a burning building on St. Urbain Street collapsed, killing eleven firefighters. The whole city mourned, and the funerals were public events. The fire brigade was an “Orange” organization, and it was a sore point among Catholics that they were not hired into the brigade. Members of the Order insisted on wearing their regalia in the funeral processions. Rumours quickly spread that the marchers would be armed with live ammunition, ready to shoot Catholics.

That spring, Con Maguire, now twenty-three, did what other young men have done when they believed the streets were dangerous. He banded together with other men and boys like himself. In their minds, there was inadequate protection offered by the parish young men’s associations, or by any of the Irish Catholic benevolent societies, temperance leagues, athletic clubs and teams. Con was already a player on the Shamrocks lacrosse team, which inspired near fanaticism on the part of their rowdy Irish Catholic supporters in Griffintown. They needed a new organization, uniquely male, that could defend the right of Irish Catholics to public spaces.

Con thus became a member of the Irish Catholic Union. Much like the Orange lodges, the Union was a benevolent society that sponsored concerts and picnics, but its true purpose was as an anti-Orange show of strength. In the first months of its founding, the Union had over nine hundred members across ten neighborhood chapters. The Protestant press immediately met the birth of this organization with suspicion. The Montreal Star called it an armed “secret society.”1

Twenty-three-year old Con was already a veteran of the newspaper trade, having apprenticed as a printer as a young teenager. Con was now working as a typesetter and compositor at the True Witness and Catholic Chronicle, a weekly paper founded in 1850 to battle anti-Irish Catholic rhetoric spewed by the Evangelical Protestant Montreal Witness. The True Witness was one of a several Irish Catholic papers founded in these years to defend Catholics against Protestant slander, each one a reminder to Irish Catholics that they were entitled to equal opportunity and representation.

The paper underwent a change of ownership in the new year of 1877, when it was purchased by Captain Martin Waters “M.W.” Kirwan, an Irish-born Catholic aristocrat and adventurer, who had just settled in Montreal. His title "Captain" came from leading a volunteer brigade of Irishmen in the Franco-Prussian War. Kirwan was a fierce Irish nationalist, deeply involved in the movement for Home Rule, and a Fenian sympathizer.

Kirwan was a celebrity from the moment he hit town. He gave public lectures on his wartime experiences in France, as well as his views on the Irish question. He took over the editorial pages of the True Witness, and wrote blistering critiques of Orangism and the Protestant press. Within months of his arrival, Kirwan had galvanized the Irish Catholic community, gazetting with the St. Jean Baptiste Infantry Company, a volunteer militia. Kirwan’s company marched in parades on St. Patrick’s Day and the Queen’s Birthday in dress uniforms of scarlet tunics and white havelocks. But the militia also began drilling.

Kirwan embraced Canadian sports of snowshoeing and lacrosse. It wasn’t long before he got to know his employee, Con, a sports star among Irish Catholics as a member of the Shamrocks, and a competitive snowshoer in the off-season. Con wasted no time in signing up with Kirwan’s militia.

Proofreading and typesetting Kirwan’s editorials no doubt led Con deeper into Kirwan’s fiery brand of Irish nationalism. As a member of the Irish Catholic Union, a volunteer with the militia, and under Kirwan’s tutelage at the True Witness, Con was fully indoctrinated as a soldier in the war against the Orange menace.

By July, the city was on edge. Kirwan revealed in his column that he received death threats from anonymous Orangemen who announced they would “go for him” on the Twelfth. Kirwan served as mediator on behalf of Catholics to convince Orange lodges not to parade on the Twelfth. Instead the lodges decided to have a “walk to church” where members of the Order would wear orange. This was praised in the Protestant press as a patriotic expression of “respect for law and order” and a “spirit of unity.”2 But soon news spread that the Orange Order’s “walk” was a parade. The Irish Catholic Union was rumored to be purchasing ammunition.

On the morning of the Twelfth, the streets were thronged with both Protestants and Catholics looking for trouble. Hundreds of men congregated in Victoria Square with open display of revolvers. Con and his friends roamed the streets with the Union. The police made no attempt to disperse the crowds.

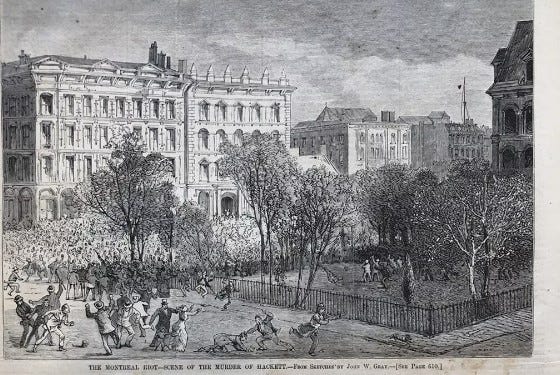

An Orangewoman was being harassed by a group of Catholics and a young Orangeman named Thomas Lett Hackett intervened.3 In the melee, he was cornered and beaten by a group of Catholic men and boys. He pulled out a revolver and his assailants did the same. Shots were fired, hitting Hackett, who died instantly.

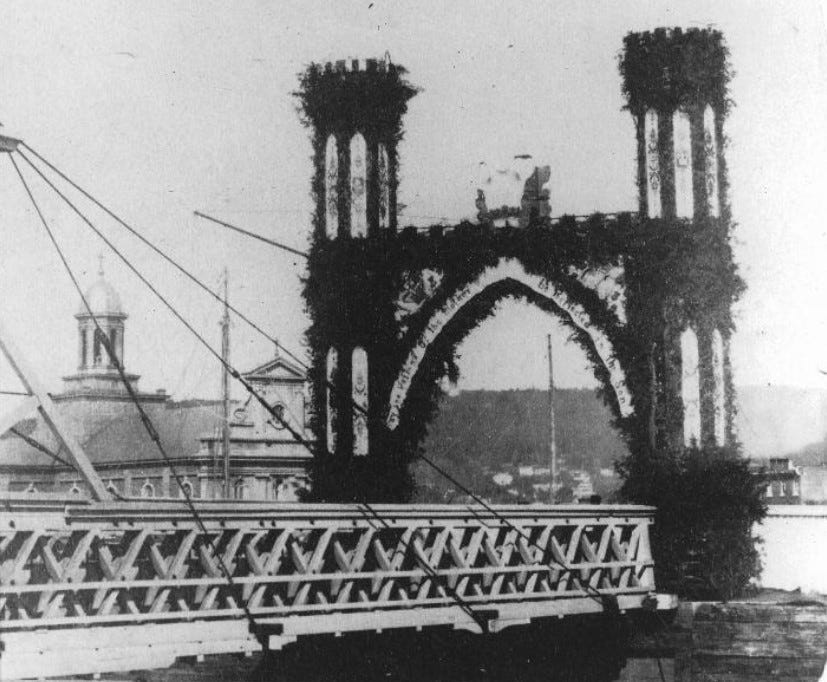

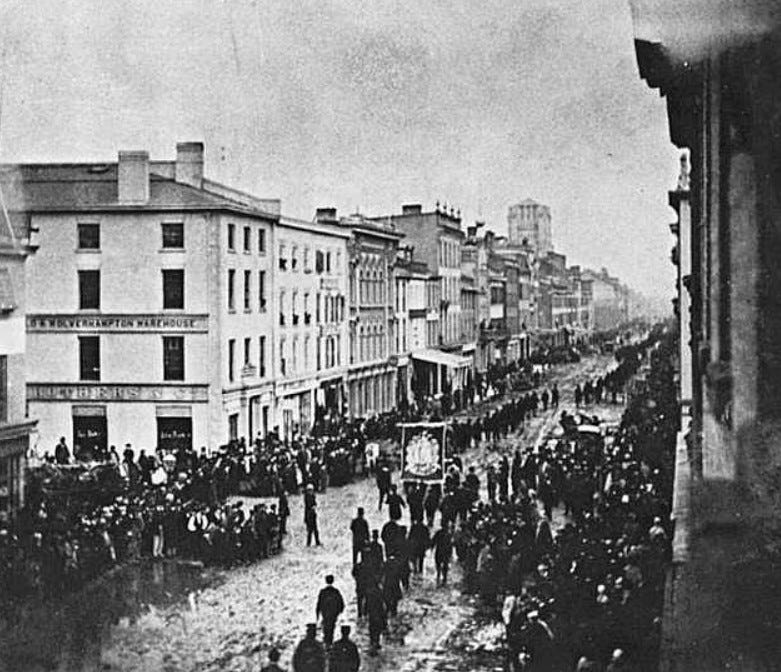

Hackett’s funeral was attended by Orangemen from all over Canada and from US cities as far away as Buffalo. Protestants of all denominations— from working class Methodists to Scottish Presbyterians to upper class Anglicans—joined the procession in solidarity. The Order got their parade.

As they approached the cemetery, the number of marchers swelled to three thousand people, far outnumbering military units deployed to keep the peace. The casket was lowered into the ground with pistols drawn. The Irish Catholic Union had warned its members not to interfere with the funeral procession, and “repudiated all sanction or approval of such acts.”4 But the day was punctuated with street fights. One Catholic man was shot in the back on Wellington Bridge. This bridge, which crossed the Lachine Canal, connecting Griffintown to Pointe St. Charles, was a frequent site of confrontation between gangs of Catholics and Protestants. Finally, the Orange out-of-towners boarded their trains home, yelling “Kick the Pope” and swearing revenge. Quiet did not come until after two am.

When a group of Catholic pilgrims returned from Rome that summer, the community turned out to meet their train. The President of the Irish Catholic Union, J.E. McEvenue, told the crowd that Irish Catholics had “fought for their rights inch by inch, and must be prepared to defend them to the death.”5

The sectarian violence soon arrived on Con’s doorstep. In February, a little Griffintown boy named Arthur Davies was kicked and called a Orangeman by a ten-year-old Catholic boy named Jeremiah Butler. Arthur’s family had the boy arrested and fined. Jeremiah, an orphan street child, had no way to pay the fine and remained in custody until the father of another child bailed him out.

Outrage over Jeremiah’s jailing made the Davies family targets of Catholic rage. A few months later, Arthur’s brother Richard was stabbed in back in the street by a pen knife on a string. Then, on the night of April 10th, his sister Martha was walking home, just a few doors away from Con’s family flat on Shannon Street,6 when she spotted a gang of men, one of whom was pointing a gun at her. Martha ran into Clendenning’s foundry across the street, and hid among the dormant machinery as shots rang past her.

On April 29th, a group of young Orangemen attended a Young Briton Orange band concert at Mechanic’s Hall. A dozen or so concert goers were heading home in the direction of Point St. Charles, when, at the corner of Colborne and Wellington Streets, they heard a voice say “Halt.” They turned to see a man looking down at them from an upper storey window. He said: “For God’s sake, don’t cross the bridge.” There were Catholics lying in wait for them. As they deliberated, shots were fired.7 At the end of the night a young Catholic man named John Colligan lay dead.

A hundred more policemen were dispatched to patrol the restless streets. The city, fearing more bloodshed, passed a law aimed directly at the Orangemen- a ban specific to religious processions commemorating political anniversaries.

July 12th came around again. Defiant Orangemen swore to march. The city braced for the worst as four thousand troops and volunteer militiamen poured into Montreal. Orange Orders from all corners of Canada were converging on the city center. Con, who had been roaming the streets with the Union the year before, was now deployed with the St. Jean Baptiste Infantry Company to keep the peace.

As the evening of the eleventh fell, Orangemen assembled at the Orange Hall on St. James Street, their militia preventing anyone passing through the Place d’Armes. Montreal’s Mayor, Jean-Louis Beaudry, who watched his city invaded by thousands of troublemakers, had no intention of letting them march. The city held its breath.

The night passed in uneasy silence. On the morning of the Twelfth, Montreal resembled an armed camp. Lacrosse grounds were transformed into makeshift barracks blanketed with rows of white army tents. Banks and businesses hastily erected barricades and boarded up windows.

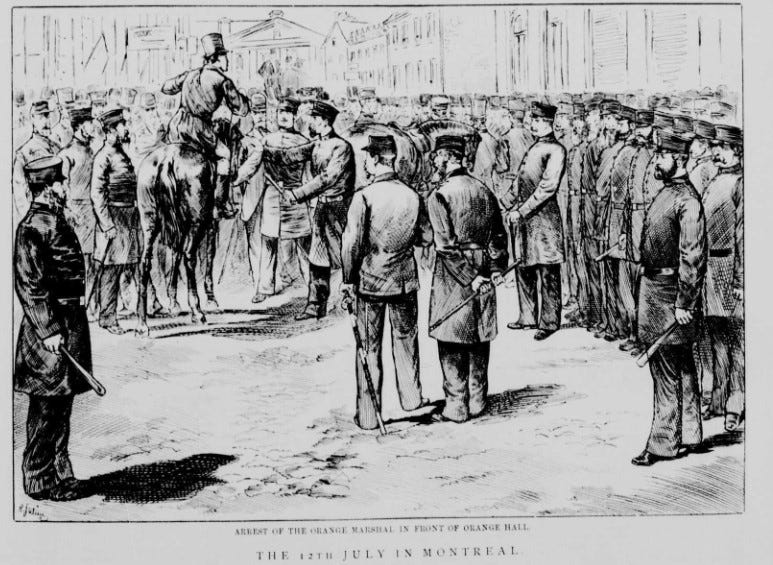

At nine o’clock, one hundred city policemen took up positions in front of the Orange Hall. Mayor Beaudry arrived shortly thereafter, followed by five hundred new constables sworn in for the event. More Orangemen arrived in their outlawed regalia, overwhelming the Hall. The streets were filled with onlookers, flouting the city proclamation to stay home.

Shortly before ten o’clock, the Mayor entered the Orange Hall and informed the heads of the Orange Order of the “folly of walking in the face of the law.”8 As the leaders of the Order started the procession, they were arrested by order of the Mayor. Another discussion ensued. The Mayor, resolute but calm, took a seat outside the Orange Hall.

The standoff lasted all morning until the Orangemen agreed to disperse. Mayor Beaudry told the crowd in English and French to go home.

Orangemen everywhere accused Catholic Mayor Beaudry of siding with the Catholic mob, and enflaming their adversaries in order to ban the procession. The men arrested on July 12th were prosecuted in the months that followed. Legal arguments turned on the validity of the Orange ban and the Party Processions law that forbade them from marching. Beaudry was burned in effigy in Ontario that summer.

On a sunny Saturday later that July, the St. Jean Infantry Company held their annual picnic and summer games on Ile Ste. Helêne. It must have felt like a celebration of sorts. Con came in first place in a foot race and was presented with a silver cruet cup.

The sectarian fever broke.

The crisis over, Kirwan left the militia, which was dissolved in 1880. The Irish Catholic Union as an organization for street defense disappeared that same year. The Orange Order ceased its parades, but actually reached peak membership in the 1920s, perhaps unsurprising given the waves of new immigrants to Canada and its nativist ethos.

Without the direct threat of Orangism to feed his pen, Kirwan grew bored of the newspaper business, and left the True Witness. He drifted west, serving as staff officer under General Middleton during the Northwest Rebellion led by Louis Riel. Kirwan later settled in San Francisco, where he made a last attempt to return to journalism before marrying an American widow and settling in New York. He died in a modest tenement on the Upper West Side of Manhattan in 1899.

Con continued to work for the True Witness under editor Henry Cloran, a passionate advocate of Irish Home Rule and the rights of the Manitoba métis. When Cloran left the True Witness in 1886 the glow was gone from the weekly. Con used connections from Protestant members of his wife’s extended family to jump to the more prestigious (and one-time Orange sympathizing) Montreal Gazette, where he remained the rest of his career, retiring in 1937 at the age of eighty-three.

Con remained true to the Irish nationalist cause his whole life. It is not known whether he softened his view of Orangemen.

There are a number of great sources on Montreal’s urban history and Orangism in Canada:

Cross, Dorothy Suzanne, “The Irish in Montreal 1867-1896,” M.A. Thesis, McGill University 1970.

Jess, Raymond, “Re-centering the Periphery: The Protestant Irish of Montreal and the birth of Canadian National Identity,” M.A Thesis, Concordia University, 2013

MacPherson, D. A. J. “The Orange Order: a Contemporary Northern Irish History by Eric P. Kaufmann; The Orange Order in Canada by David A. Wilson” Irish Economic and Social History, Vol. 37 (2010), pp. 172-174

Tock, Annie, “Orange Riots, Party Processions Acts, and the Control of Public Space in Ireland and British North America, 1796-1851.” Ph. D. Dissertation, University of Maine, 2020.

White, Randall, “Orange Order in the great white north : Canada’s storm troopers of the Tories revisited” Counterweights, Nov 14th, 2005

The Montreal Star, July 11, 1877

The Montreal Gazette, July 11, 1877

True Witness and Catholic Chronicle, July 18, 1877

Montreal Daily Witness, July 11 1877

The Montreal Star August 14, 1877

For readers of Griffintown 1861: Molten Metal, Martha Davies was in fact a tenant of John Gordon

The Montreal Gazette, May 10, 1878

The Montreal Gazette, Jul 13, 1878

That explains a bit about why Stan Rogers needed to do a song about it

A fascinating story well told. Montreal's (and Canada's) history is fascinating when you get down to the granular level.